I went to school to be a journalist. My financial aid package required that I take on a work-study job. So during my first year of school, I worked with Jumpstart, an AmeriCorps program where they put college kids in Title I preschools. As part of that job, I was an assistant to the teacher a couple hours a week and I worked one-on-one with a preschooler. I fell in love with that student. I was so inspired by the teacher who was in that classroom, and I was able to directly see the impact of what the teacher was doing with her students and with her families.

So I decided to change my career path to early childhood education. I realized then that I’ve always loved working with kids. I remember in fifth grade, we had kindergarten buddies. We would see them every Friday, and we would read to them, and they’d read to us. I remember doing craft projects together, and I remember going on an Easter egg hunt and loving that experience. I always volunteered with kids in high school, especially over the summer. So, it’s always been there, my love of working with children.

But it wasn’t until I was in that classroom with that kid, with that teacher, that it really clicked to me that I could make a career out of this.

It’s become my passion.

It’s the little moments that happen every day:

When I see one of my students understanding a concept that I’ve been trying to teach them.

When I see them making a connection with another peer.

When I see them using the strategies I taught them about how to ask somebody to share or how to enter a play situation.

When they’re able to write their name independently for the first time and they feel excited and say, ‘Look, I wrote my T!’

It’s a combination of all those moments that reinforces for me every day why I chose this as my career.

I also love hearing from the families: ‘My kid loves being at school. We’re so thankful that they’re here with you.’ Or, ‘I hear them coming home and singing that song (or using that new vocabulary word, or drawing a picture about what they did today). And they’re so excited. They love coming to school.’ That, for me, is what makes it worth it — why I wake up every morning for my students.

We recently finished up a bread unit, and the kids loved it. I asked each family to send in bread to share with the class that’s special to them, either from their culture or bread they love. When each child brought their bread in, they were so excited to share a piece of them and a piece of their family. We did ‘taste testings’ and then used chart paper to record if they did or did not like it. We have a diverse class, so it was exciting to try different types of bread.

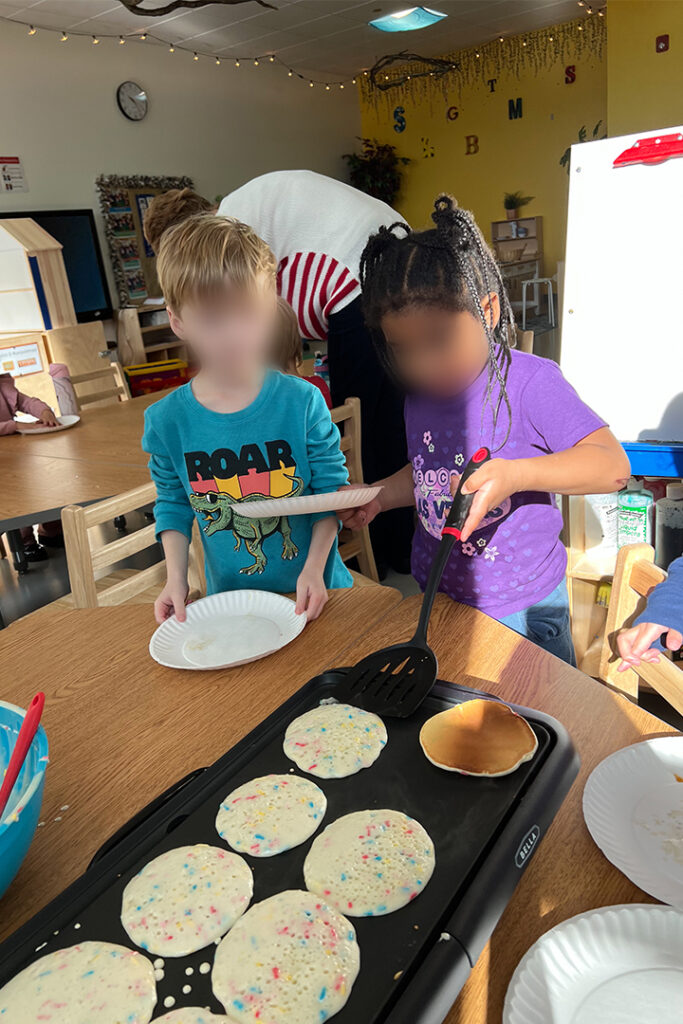

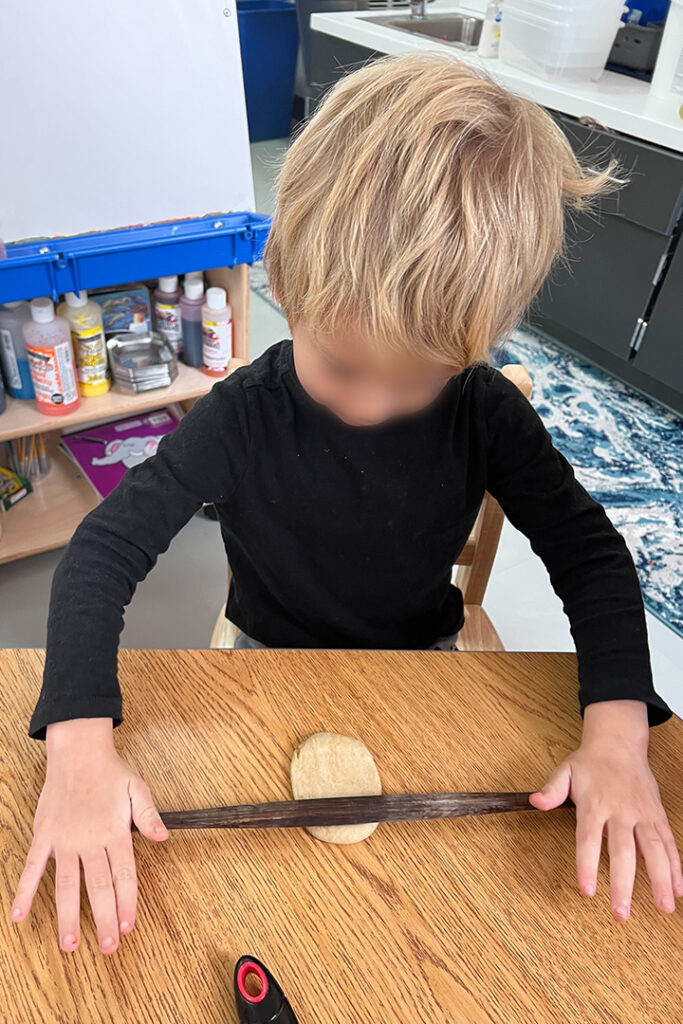

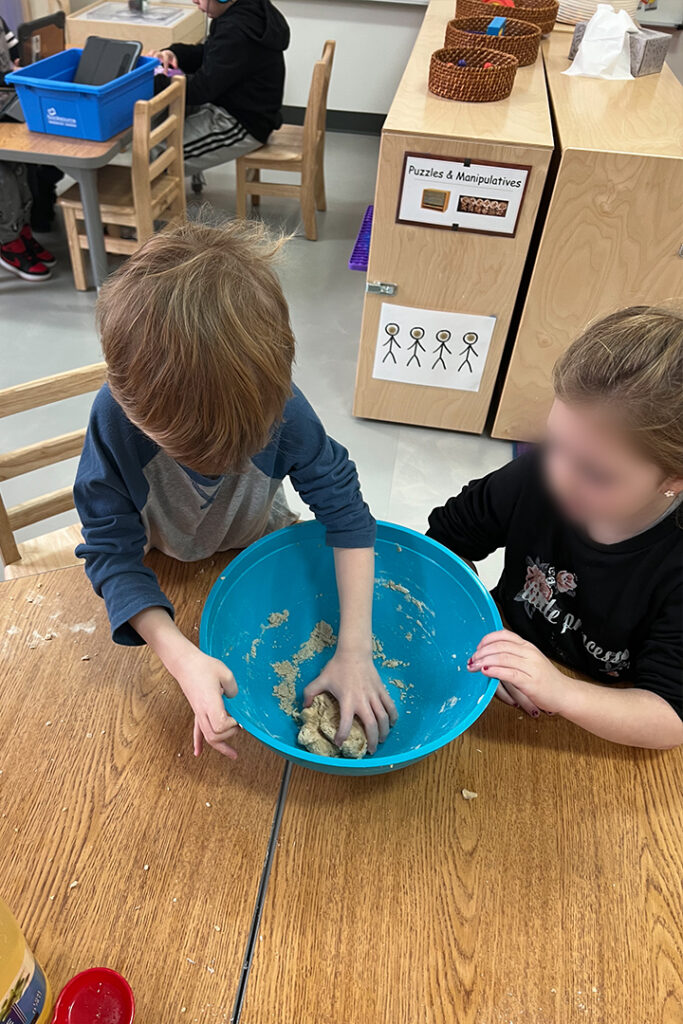

We also made bread at school. We made pancakes; we made roti, which is an Indian bread that I make at home. We made gingerbread men; we made pizza. We’ve been using baking to tie in all different areas of development, like measuring, counting, and following directions, and connecting to their interests and their cultures. It’s gotten me really excited to keep that going.

Getting a class full of children ready to bake requires a lot of steps. Before we started the baking process, we talked about what a recipe is, and we learned about ingredients and measurements. We talked about the importance of following the directions — because if you just put a bag of flour into the oven, that won’t make anything. We practiced how it’s important to go step-by-step in order.

After we built that foundation, we read off each ingredient and went around in a circle to scoop and take turns mixing. I want them to be involved in every step. It gets messy, but it’s worth it because they’ve gotten that firsthand experience. If I just put all the ingredients in and mixed it for them, they wouldn’t understand what whisking means or what the consistency of something has to be in order for it to make a bread.

Units like this help with executive functioning skills. Not only following a set of directions, but being able to wait their turn, and being able to wait for the dough to rise. They were so excited to cut out their gingerbread cookies, but you have to let gingerbread dough cool in the fridge overnight first. They had to learn to wait a whole day. Then they had to wait again for the cookies to cool before they could decorate them and eat them. It helps with self-regulation, and the measuring, pouring, and kneading helps with fine motor skills.

I’m not going to test them on the ingredients of pancake batter. I’m not going to quiz them and ask them to re-make it for me. Instead, in Pre-K, we’re providing the foundational skills they’re going to need for the future.

There’s a study that shows teachers are making over 1,200 decisions a day, which is more than a brain surgeon. It’s not just decision fatigue, though. It’s the fact that I’m always on.

I was in a group chat with my husband and some other family because we were planning a vacation together. During the workday, there were 30 text messages about what we were going to do to help plan for this vacation. I wasn’t sure how to convey, ‘I’m teaching. I can’t participate in this conversation. I’m not sitting behind a computer where I can decide to stop answering an email to look at this text message or Google restaurants instead.’

When I’m here, I’m on. When I’m not in a specific break time, it’s full-on. Starting at 7:30 in the morning, I can’t use the bathroom when I want to, because I have to be present. This isn’t a job where you can go in and out of your workflow as it works for you. When the kids are in front of you, you have to be ready. You always have to be present with them. Otherwise, it’ll be chaos.

Earlier this year, I went to the National Education for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) annual conference in Washington D.C. where I was presenting on the importance of play in kindergarten and meeting with legislators to discuss developmentally appropriate practice — which is a way of saying that we should use teaching methods that meet each child where they are and use their strengths. I met a family member for dinner that day, and they asked, ‘What do you do at a conference? Do you learn how to change diapers better?’

I know it was kind of a joke — but it kind of wasn’t. They didn’t understand what professional learning I could still be doing as an early childhood educator. It seems like the perception is, overwhelmingly, that I’m a babysitter.

Prekindergarten teachers set up kids for success. If you ask any kindergarten teacher, they’ll tell you, ‘We don’t need the kids to come in knowing their letters and numbers and how to read — that is a part of our curriculum. We need them to come in with executive functioning skills. We want them to have the social-emotional readiness to be able to play with their friends without fighting. We want them to be able to follow directions. We want them to be able to put their coats on and zip them up by themselves so that they’re ready to go home.’ Those are the skills I work on.

I definitely think kindergarten is not developmentally appropriate — I think they do too much sitting at the tables for that age level. But that’s the way that the system is set up right now. So students need prekindergarten in order to be ready for that experience when they get to kindergarten. They need to be able to know how to listen to a story and discuss it. They need to be able to know how to line up when the teacher asks for them to line up and how to interact with the material in an appropriate way. They need to be able to build with Legos instead of throwing them.

I get a lot of questions about my thoughts on sharing. I teach children the skills I want them to have as adults. If somebody came up to you as an adult and asked for your car, you would say no, and for good reason. We need to extend the skill of boundaries to the broader context of what we want kids to be able to do in the future. So we talk about how sharing the blocks or sharing the magnet tiles lets you have fun with your friends. But I don’t make anyone share if it’s something that they’re specifically working on, or if it’s something that belongs to them.

Instead, I teach them how to communicate. They can’t say, ‘These are my Legos and I’m using all of them right now.’ But if they’re using specific Legos to build an airplane, they can communicate that. Or if it’s a material that there’s only one of, like a book, a peer can ask them, ‘Can I read that book with you?’ They can say no. I help give them the words, like, ‘You can have it when I’m finished, but not right now.’

One thing that’s different from when we were in prekindergarten is the amount of time spent in a group setting. We’re not sitting on a rug together for hours chanting the days of the week.

I think there’s something to be said for reading a story as a group or doing activities together. But I think the majority of the day should be spent with the kids leading their own learning and making their own choices. In prekindergarten, that looks like playtime.

I’m still evolving in my practice. I want to grow in how much autonomy and agency I give my students to be able to make those choices — to play in the room and to move in our space. I want to radically shift away from doing group activities and let them engage with their environment and the materials. So I’m working on that. I’ve seen other teachers do it successfully.

Being in a public school system, I don’t have as much autonomy. We have to eat lunch at a certain time each day and our specials (art, music, gym) classes are scheduled for us. But during the time that I have with my students in the classroom, I can structure it how I need to for the kids.

I had a student — let’s call him Reggie. Reggie’s favorite toy was Magna-Tiles. He would play with them almost every day. I used his interest in those Magna-Tiles to help him learn not only academic skills and higher order thinking skills (like color mixing, architectural integrity, and spatial reasoning) but also to advance his social-emotional learning. Reggie quickly became a confident designer, making large 3D structures, but he had a difficult time playing with other children. They wanted to join his play, but Reggie struggled to give up control and knocked down their creations. I coached Reggie through this, getting him to understand that although he had become the classroom Magna-Tiles expert, he needed to also let other children make decisions about the play. We came up with a list of strategies he could use, and through play, Reggie grew tremendously.

When Reggie got to kindergarten, he was no longer allowed to play. Suddenly, he was expected to spend the majority of his day in one seat. His kindergarten teacher told me he was struggling to get his work done and was constantly disrupting the other students’ learning. I told her about his love of the magnet tiles and how I used them as a tool to help him learn and self-regulate. Unfortunately, since Reggie was now in kindergarten, there was no time in the classroom for play.

His teacher and I decided to create a work-for-play system where he could spend some time at the end of the day playing in my classroom if he got his work done. His teacher noticed that while he tried harder, sitting for so long was still difficult for him. If play had been incorporated throughout the day in his kindergarten classroom, Reggie would have been able to focus even better on his work and wouldn’t have had to come back to me.

This made me wonder how many other children were struggling because there was no play in their kindergarten class. They’re still just five. They should be allowed to move and interact with their peers. They learn through hands-on activities and through manipulating their environment. So we need to give them those opportunities.

Through the Teach Plus Illinois Early Childhood Policy Fellowship, a group of teachers and I are trying to promote play in kindergarten. The state of Illinois adopted an assessment tool several years ago called the Kindergarten Individual Development Survey (KIDS). Every kindergarten teacher is mandated to use KIDS, which is an observational tool to note the students’ social-emotional development in an authentic situation (play). However, most kindergarten teachers don’t have time to allow for play in their classrooms because kindergarten is set up like a traditional school where they’re sitting at their desks and doing worksheets.

The other fellows and I did a case study of some Illinois schools that have switched to a play-based model and compiled a list of things that have gone well, as well as barriers and recommendations. So we’ve been promoting that and talking about the importance of play in kindergarten and how kindergarten is still early childhood. Kids are still in the concrete operational stage in their development. They need that concrete play to be able to process and learn new information, and play is still the best learning tool. Not worksheets.

I’d recommend that parents of young children advocate for play in their children’s classrooms. Go to your school’s administrator and ask if their kindergarteners have time for play during the day. It’s really important, and having parents on our side really helps teachers do what’s best for the students.

Feeling supported and feeling like you have a voice is what keeps teachers in the classroom. Kids are kids, and we all know there are going to be challenges and there are going to be difficult years. There’s going to be that class that just gets to you. But what keeps the teacher in the classroom is knowing that they’re supported — by coworkers, by administration, by the broader community, and with the ability to have a say in what’s happening.

I have a teacher friend right now who’s considering leaving. One of the things that’s gotten her to this point is the new curriculum. In Chicago Public Schools, your Local Schools Council votes on and approves the curriculum. All the teachers on her Local Schools Council wanted one curriculum, but all the parents wanted another, and the administration wanted the one the parents wanted. They ultimately went with the curriculum that the parents and administration wanted.

The teachers know that the new curriculum isn’t the best way to teach the kids. They’re saying, ‘We voiced our concerns at the meeting. But nobody listened to us.’ The parents liked what they read about the curriculum, and they liked the price. But for the actual implementation, only the teachers do that, and their voices were not considered in that decision.

My friend is struggling to teach with this curriculum. She says, ‘My kids are not getting it. But if my principal walks in the door, they want to see me on page 37 in the second unit.’ She’s having a hard time balancing the needs of her post-pandemic kids — and what she knows is best for her kids — with this curriculum.

So I think being valued as experts would help keep a lot of teachers in the profession. Not just having a seat at the table, but being heard.

The resiliency of children encourages me. The kids I have right now are the pandemic babies. They were teeny tiny when the pandemic hit, and so many of them don’t have social skills. They didn’t even go to things like toddler time at the public library because all of that was shut down during COVID. So they’re coming with so many needs that I haven’t seen in the past.

But they’re just so resilient. If they have a loving, supportive adult and teachers to help guide them through navigating this weird new thing called school, then they are able to do it. They’re able to learn, they’re able to engage, they’re able to participate. They’ve grown so much in their skills.

Each year of kids — every age — lost out on some sort of skill set in their development when they were forced to stay home because of the pandemic. I see so many kids coming out of it catching up and doing all the things that we know kids do. But that’s only possible with the support of an adult that really cares about them.

I am in a general education class, so all of my students are gen ed students. But in this building, we have 16 Pre-K classrooms. We have gen ed classrooms, we have blended classrooms, and we have intensive support classrooms.

We also have a K-3 program on this campus. It’s only for students who need support. So a lot of them have autism or medical needs that can’t be supported in a gen ed classroom. We have a lot of cool things at this school, like a sensory room and an adaptive playground. We have all the supports — social work counseling, physical therapy, speech, occupational therapy. So they get the full wraparound services here in this building, which is a great resource for parents to have.

There are a few schools like this in Chicago Public Schools that focus specifically on early childhood. Having this community of other early childhood educators is amazing, because a lot of schools have only one or two Pre-K classrooms and the rest are K-8. When administrators come to the lower grades, they wonder why our students are playing: ‘Where are the worksheets? Where are your anchor charts?’ If they ask to see a writing sample, you’re going to show them artwork, and they may be confused.

So to be in a building where my work is completely understood and accepted is amazing. If you walk down the hall, you’ll see there’s a crawling cube there, there’s a hopscotch there, there’s a slide there, there are a few wagons and bikes. So if I have a kid who needs a movement break, they can take the bike and ride up and down the hallway. It’s just accepted. Whereas if I did that in a building with older kids — I don’t want to generalize — but typically it’s like, ‘Why are you running down the hallway? You need to walk in a straight line. You have to be quiet now.’

I feel comfortable trying new things and opening my philosophy of play in an early childhood classroom. I have other early childhood teachers who I can collaborate with, plan with, and get ideas from. We talk through problems and brainstorm together.

I feel a lot more confident and accepted.

–Margi Bhansali

Pre-K Teacher at Beard Elementary

Chicago, Illinois

Share a link to this story

…or see Margi’s posts on:

Wondering how you can support Margi and her students? Here are a few ways to help:

Contribute to Margi’s Amazon Wishlist

Donate to a project on Margi’s DonorsChoose

Volunteer at Chicago Public Schools