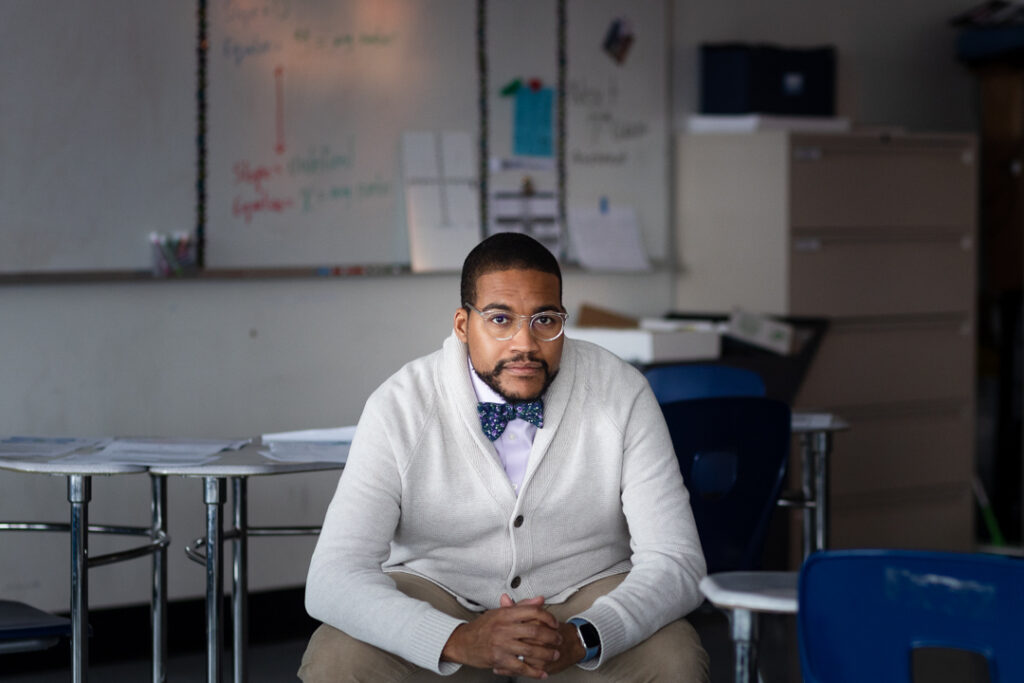

I was an econ major. I wanted to work at the Boston Federal Reserve and go to the London School of Economics. But I graduated in 2009, and there were no jobs available, due to the housing crisis and Great Recession. So I started working at a local public charter school.

There was reinforcement coming from other people — statements like, ‘Hey, there aren’t many Black males in the public school classroom. You could be a good role model. We need more people who look like you and who come from the background that you have.’

But I was also asking myself, ‘What do I want to do?’ It was hard to balance the encouragement from people who saw something in me with trying to explore my interests. And I found that while I was asking myself what I wanted to do, I was getting pretty good at teaching. I enjoy interacting with people. I like seeing people have success. And for me, teaching is an art form. It pushes me to be creative, and it keeps pushing me to get better.

I worked at a nonprofit with young adults, teaching them customer service and management skills, but also tutoring them in math for their college entrance exams. With that, I fell in love with math. So I started taking some classes in human development, and I decided to give math teaching a shot. I haven’t looked back since.

I still think of ways to incorporate my other interests, whether in or outside the classroom. Because to some people, I’m their idea of a teacher, and that’s all I am.

But I’m also Francis.

I had two Black male teachers growing up, both during high school. One was my direct teacher, and the other person was a role model for me. I didn’t have his class, but he supported me during my senior year.

I ran for senior class president as a joke. I wasn’t taking it seriously. But then I won. Suddenly I had to fulfill the role and all of the responsibilities. There were people around me who weren’t supportive, and I contemplated quitting. But I stuck it out, because this teacher encouraged me. He kept telling me, ‘Hey, be that leader. Keep pushing yourself forward. Know that this is bigger than you. You have to live up to the expectations of the senior class and deliver what they want. This is what you applied for.’ And that pushed me to keep going.

When things are really challenging, I still try to keep perspective: ‘Why am I doing this?’ And if it’s for service, if it’s bigger than me, then I need to put others first and center around them.

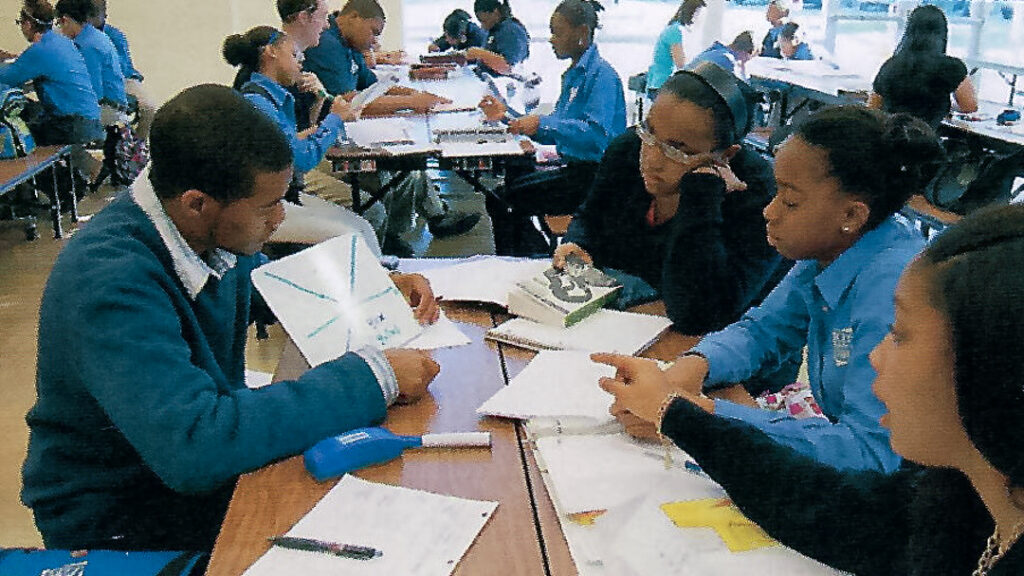

There are two ongoing things that keep me in the classroom. One is building relationships with my students. I could build relationships with individuals at the Boys and Girls Club or by being a Big Brother. But to go from the beginning of the year, when I am still learning names and trying to get to know them, and then get to the point in the school year where we have inside jokes, maybe we have a secret handshake… maybe they keep asking the same question over and over, to annoy me but out of love. Or maybe they just want to share things that have happened to them. When you have that relationship, and students can see you as a person first, and they get to understand some of your interests, then I feel like it helps to garner some respect. They see me as someone who truly cares for them, not just someone who cares about what I’m teaching them.

The other piece that keeps me in the classroom is that I’m always trying to get better: ‘What could I do differently? How could I do this more efficiently?’ And then being able to say, ‘Alright, let me try that. Let me enact that.’

In teaching, you can plan the greatest lesson, but it can go terribly, depending on the circumstances: the day of the week, the time of day, if students are hungry, if something has happened in the community. So I’m trying to always adapt and make adjustments to deliver the best lesson that I can. When things go well, I try to replicate that. And if they don’t go well, I want to work on that and improve.

I don’t know if it’s fully healthy, but I definitely keep aiming for how I can I do better for the students.

Athletes have a season.

They have a long period of intensity and then a lot of ‘time off.’

If we can evaluate and accept that athletes have a season, then can we begin to understand that teachers have a season? Can we respect well-earned time off?

One of the things we talk about in school is that it is so important that kids feel connected to an adult in the building. And since the pandemic, we have seen more of our kids struggle because they do not feel connected. They feel like they don’t belong, that they don’t matter. Our classes create that sense of belonging. We have longevity with our students. It’s not, ‘You have me for one class, and I’ll maybe see you in the hallway the next three years.’ Our classes allow us to cultivate stronger connections with students.

Middle school teachers are a different breed. Because middle schoolers are weird. They are past the elementary school phase of wanting to please all the adults in their life, but on average, they still want to please. They want acceptance. They’re transitioning to the high school phase of finding their identity. And they’re going through puberty.

Middle schoolers are trying to figure things out: ‘What does it mean to have friends? What does it mean to be bullied? And how do I deal with all this stuff?’ So middle school teachers are important, in terms of trying to help that phase of human development and help kids understand what could be potential future options for them.

In Boston Public Schools, we have high-stakes testing in high school, where students really need to have a good foundational understanding of Algebra 1, Algebra 2, and Geometry. So as a middle school math teacher, it’s my role to make sure students have a good handle on the foundational skills of pre-algebra. They need to develop an understanding of variables and how they interact with each other. They need to become comfortable with the fact that math is no longer just numbers, and they need to learn how to represent math through tables, graphs, and letters.

It’s important for a teacher to communicate those changes in math in a way where students can feel comfortable exploring it and developing confidence. Because students who aren’t successful in their ninth grade Algebra 1 class tend to get held back, and if that happens, they’re more likely to drop out of school.

My goal is to help students see both the mathematics and the non-mathematics options. It can’t just be, ‘Well, you need to learn this to do Algebra 1, so you can do Algebra 2, so you can do well on the test.’

What are the life skills that students need to be successful? The ways students will need math as adults are not often put on high-stakes tests. We don’t need to solve a linear equation or to graph a system, but we do need financial literacy and basic statistical understanding. So how can we push to ensure students graduate with the skills to do their taxes and discern various statistical graphs in newspapers, magazines, and on TV?

Right now, teachers are stuck between a rock and a hard place, because there are demands on us curricula-wise for what we need to teach students — the standards and Common Core. But there’s this other pressure to make learning human-centered and relevant to real life. We’re not having enough discussions where we meet in the middle.

We need to talk about the skills that are helpful in real life, and we need to think about how to restructure content to support that. And then outside of that, we also have to think about opportunities for students to explore their interests. They are not all going to become mathematicians, math teachers, or scientists. That’s why it’s important to have the arts, a school yearbook, a digital magazine… we should be pushing for students to pursue what they’re interested in. We need to consider these other avenues to encourage students to explore their interests, instead of focusing solely on what is required through state testing.

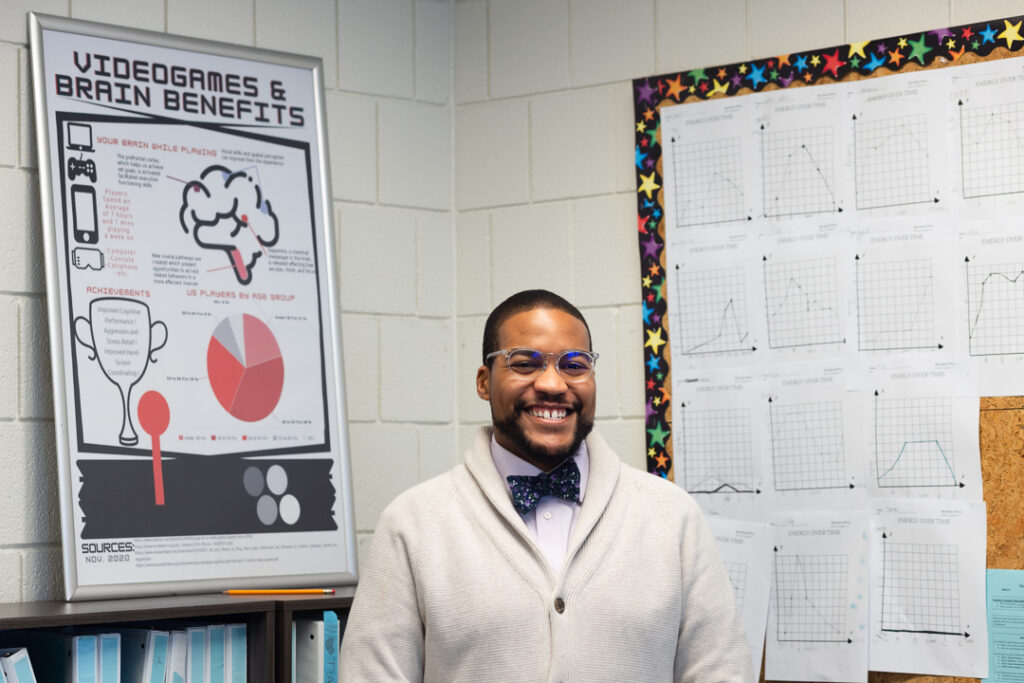

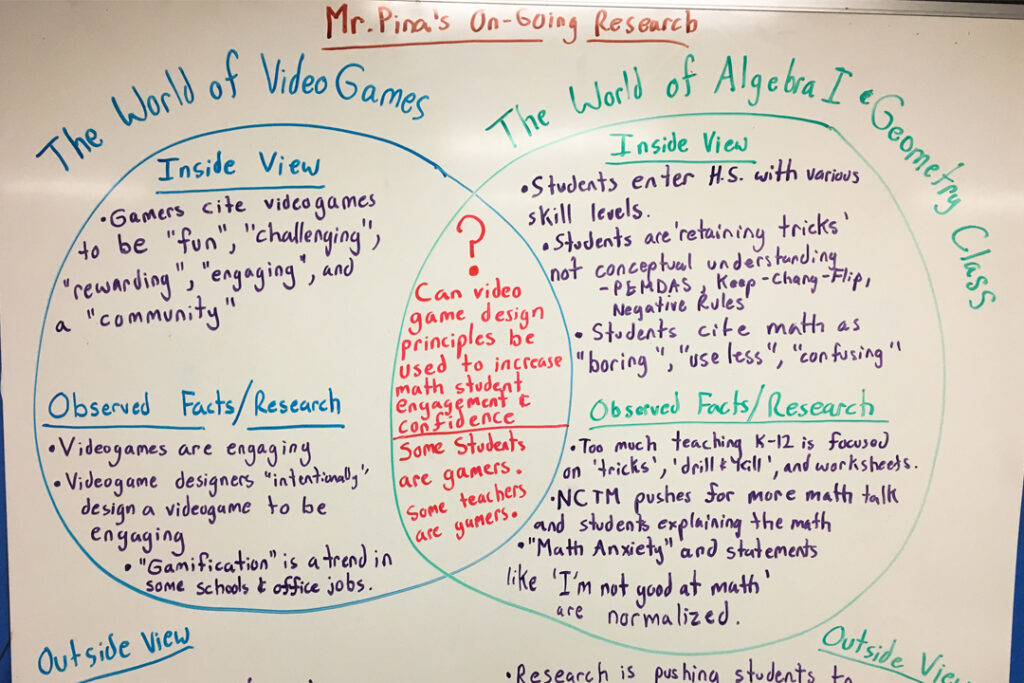

This poster came from a project I did with 10th graders before I taught middle school, where I helped them go through the process of creating their own infographic based on their interests. Video games tend to be seen as toys that are not academic and not really engaging. Adults aren’t always asking children, ‘What makes video games so interesting to you? Why do you enjoy them?’

Some of the benefits found in research are not only in terms of cognitive development and hand-eye coordination, but also in terms of building resilience. Like if you’re playing a game and you keep losing, or your character keeps dying, there’s resilience and grit in saying to yourself, ‘Let me try again. How can I get better at this?’

You also develop a foundational understanding of how something works in a video game, and then you build on it. So for example, in Mario, if I’m running and I have to make a jump over one gap, then the next time, there will be two gaps, and I have to figure out that I need to double-jump. Then the next time, there will be two gaps plus an enemy to battle. So it consistently gets more challenging over time, where children are learning how to use what they’ve learned before as foundational knowledge and build upon it.

That’s what I do with math. It’s like video game design. I’m building these foundational experiences that I hope students can retain, and then I’m asking them to apply the concepts they’ve learned to more complex situations. How am I creating opportunities that are low-risk, but high-reward? How am I creating opportunities where the payoff is clear to students? I want to say, ‘Look what y’all did. Wow, be reflective about that, you’ve had some success.’

Each time, we’re building. They get past the first level, and then they do the second level, and it’s my job to keep them engaged; I’m competing for their attention against everything on social media and streaming TV.

Ten years in this game, and I plan to stay teaching in a classroom for at least a good while. I want to be consistently good at this.

I think the biggest thing that could be done to help more teachers stay in the profession, besides respectable pay, would be to give teachers space and time to be more creative and encourage them to bring their full selves in to the classroom. Incorporating my interests into the academics not only keeps me grounded as a person, but also helps me consider creative ways to build a classroom community.

I keep two photo albums in my classroom, along with two of my own collections of poetry, because curious students tend to ask curious questions. I enjoy when my students ask, ‘Why aren’t there pictures of me?!’

‘When will you print pictures of me?’

‘Mister! You write poetry?! So do I!’

That is why I deeply appreciated that the senior class of 2021 asked me to be one of the faculty speakers at their graduation, even though I hadn’t taught that group of students in two years. While it took me too long to become comfortable bringing my full self into the classroom, doing so allows me to share my interests and build connections with students.

Fact is, teachers are not always planting the seed. Students aren’t empty vessels. Children come in with interests, and we water the plants, and we hope some leaves will grow.

–Francis Pina

Middle School Teacher at Charlestown High School

Boston, Massachusetts

Share a link to this story

…or see Francis’s posts on:

If you’re inspired by Francis’s story and would like to contribute to a cause he cares about, please consider supporting:

Lupus Foundation of America (in memory of his mom)

Year Up (for being his steppingstone into teaching his own classroom)