My parents met working in a group home for adults with intellectual disabilities in Rhode Island. My dad stayed within that profession, moving all the way up to his position now. He’s the commissioner for Connecticut Developmental Services. I grew up hanging out with adults whose parents were no longer around, and my dad didn’t want them in group homes for Thanksgiving — a kid named Walter would come for Thanksgiving or Christmas.

I grew up really immersed in the adult world of individuals with intellectual disabilities. My dad doesn’t have specific clients anymore because he’s working for the state, but he still goes to different programs. My mom is a social worker at a high school. She has volunteered with the Special Olympics my whole life — she’s the announcer and organizes the student volunteers from her school. We used to go to the swim meets growing up.

I went to a daycare that was attached to my dad’s group home in Rhode Island, and that daycare was integrated with individuals with intellectual disabilities. My best friend at daycare, Cassandra, was a nonverbal individual with autism. James was my friend with Down syndrome who I played dinosaurs with all day. We were all friends with Olivia, who didn’t have an intellectual disability. We were all in the same class, learning together.

When we moved to Connecticut, my parents tried to have me stay involved, even though it might have not been as integrated. In high school, we had a program called Unified Sports; I was a ‘mentor’ in that program, and we worked with athletes playing basketball and soccer.

I’ve been working in advocacy my whole life. So when I got the offer last year from my principal, I was like, ‘Yeah, that seems right. It seems like the next step in my life.’

I decided to become a teacher during COVID. It was an interesting choice. It started with me posting online that I was open to work, specifically work that entailed helping students write their college essays. A former teacher, one who’s super influential in my life, reached out and said she was going to be taking leave for a little while. She asked if I would be her long-term sub for the creative writing program, which was exciting.

Half the class was in person on Mondays and Tuesdays, everyone was virtual on Wednesdays, and the other half came in person on Thursdays and Fridays. After that experience, I transitioned into working as a paraprofessional in the Life Skills classroom at the same high school. So I was able to experience two huge parts of my own high school experience, now from the other side of the desk.

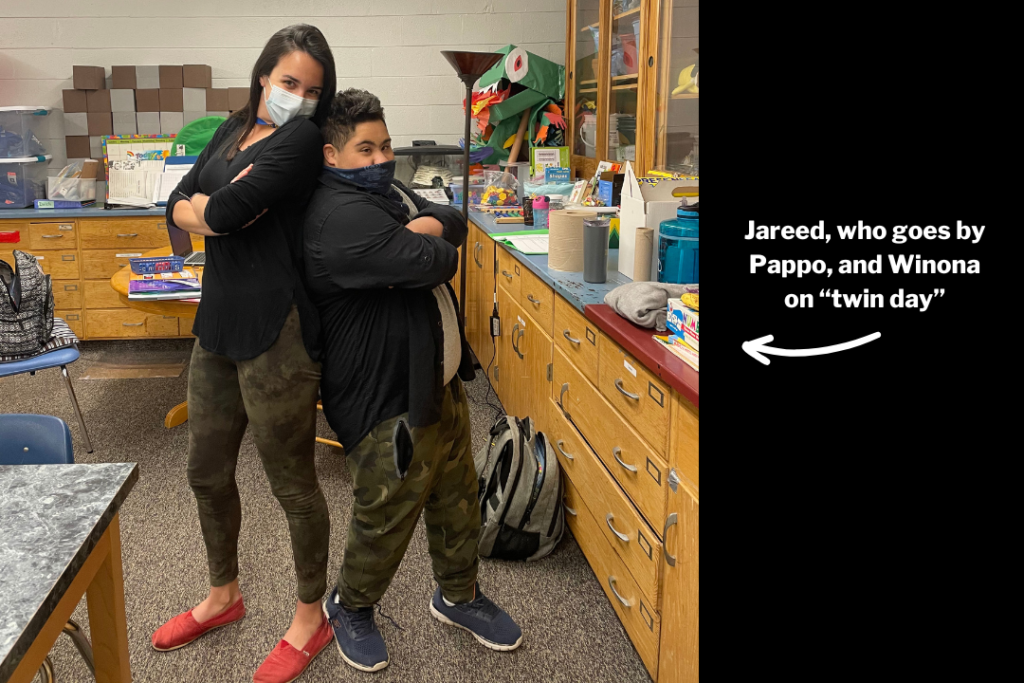

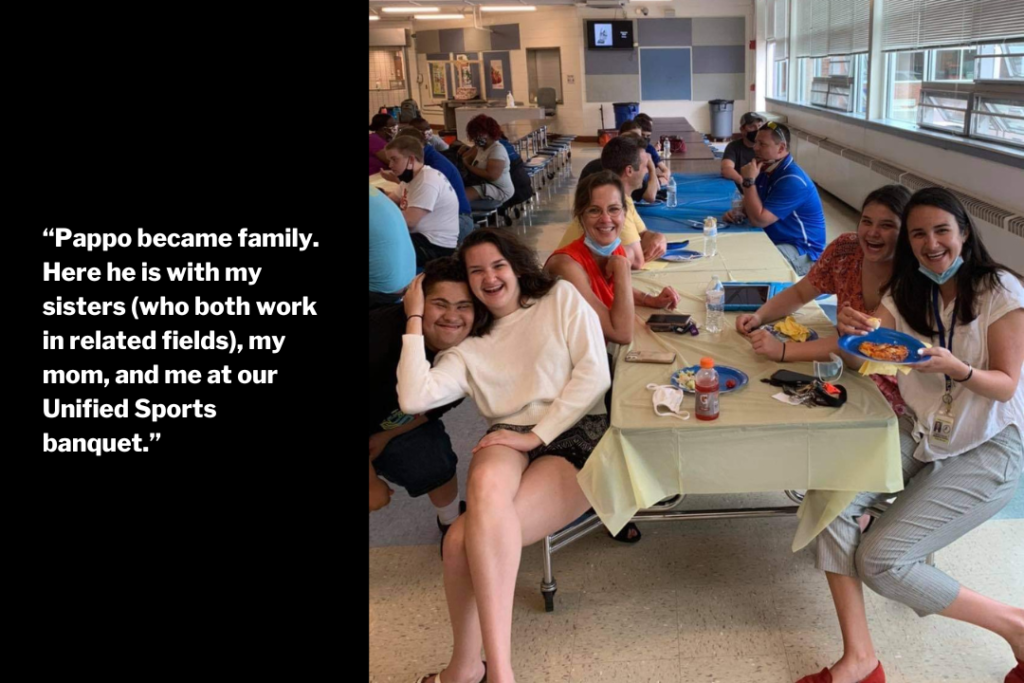

When I entered that Life Skills classroom, I immediately bonded with a student named Jareed, who everyone calls Pappo. My younger sister Stella, who was still in high school at the time, worked in that same classroom through a mentor program and also formed a strong connection with him. They even went to prom together. Pappo came to Stella’s graduation party. We still FaceTime — he tells me what he’s up to and still calls me Miss Scheff.

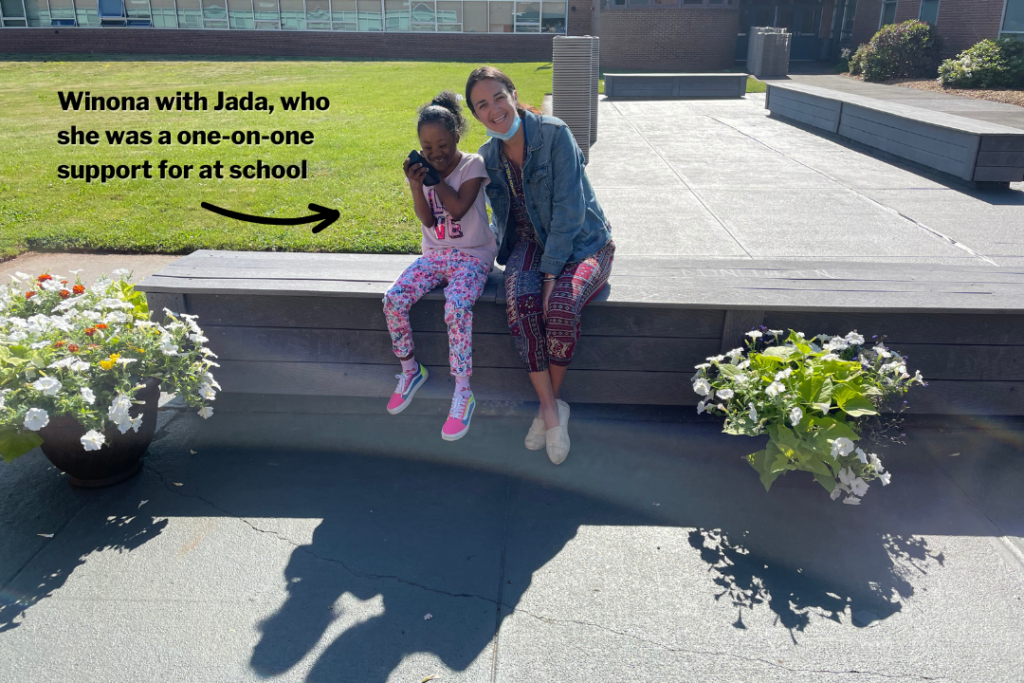

People often think teachers go into education to change students’ lives, but Pappo and another student, Jada, changed mine. They reminded me where I want to spend my energy and what I care most about.

When I applied to City Teaching Alliance, I was assigned to a middle school in Baltimore. My original intent was to teach at the high school level, but I’m grateful. I feel like I may have been too recently removed from high school.

I don’t think I understood how much emotional responsibility I would have. My students come in and seek constant comfort and validation. It takes a lot of emotional capacity. There’s a youthful innocence in all of our students, but also there’s this budding maturity, or desire for maturity, and so they still have this hope, but they’re also starting to become jaded by the world. It’s a weird juxtaposition.

I started in seventh grade with my host teacher. She was in her second year, and her first year teaching was during the pandemic. I was learning alongside her, and she had taught in France the year before, so she had a lot of insights. Then after that, I became an eighth grade teacher, moving up with those same students I had in seventh grade. It was a new experience being solely in charge, and I taught English Language Arts for two years.

I had two different coaches through City Teaching Alliance during that time, and they would come in and help me. I had a fabulous literacy coach who worked here. She’s since moved on to a high school, but I credit her a lot with teaching me how to be a teaching professional, especially in a community that I didn’t grow up in.

I grew up ‘up north,’ where it snowed a lot, and not in a city. The community I grew up in had many individuals with disabilities. In the back of my head, there was always an interest in helping the broader community of individuals with differing abilities, and it’s why I applied to CTA. I got dual certified — I didn’t want to solely do special education, and I didn’t want to solely do English. My coach knew that I had a long-term goal of working in advocacy and dropped the hint in my principal’s ear. My principal asked if I’d be interested in making the switch from general education to special education.

In general education, a lot of people think the biggest difference from special education is the abilities and personalities of the students, but I don’t think so. I assist in the bathroom and things of that manner, but otherwise, all the students have similar personalities and interests. I would say the biggest difference is that we don’t have a scripted curriculum we can work from to adapt. Teaching special education, I am left to my own devices. I’m learning how to make my own lessons from scratch and how to plan my instructional time, which has its pros and its cons.

All of my students have individualized education goals. The broader system wants me to be teaching the general education curriculum and modifying it for my students, which is sometimes beneficial and then sometimes not. My students are not going to write the five-paragraph essay that the eighth graders are writing, and it wouldn’t be beneficial to try to get them there in terms of their long-term goals.

I have some students with autism, some with an intellectual disability, some with traumatic brain injuries, two students with Down syndrome, and another with a hearing impairment. Some of my students with autism are verbal and other students are nonverbal, so their modes of expression are very different. My students with intellectual disabilities also range from verbal to nonverbal. Some need physical assistance and others don’t.

What disappoints me is the lack of continuity where there could be continuity. One of my homeroom students uses a communication technology device; it speaks and reads, and she uses that. I wish that more of my students had communication devices, but it’s a long process to get one.

We have core boards that are printed and laminated so students can point to core words. I’m working on sign language with my students, and I’m not fluent, but I know some basic elements to be able to communicate with them. Mostly, they communicate through behavior. For example, a student will express in some way that she’s upset because she doesn’t want to do the assignment.

For my homeroom, my students are generally more verbal. I have two students who are nonverbal, but they are socially aware, and they have other modes of communication they can use to articulate themselves.

Every day, we start by doing a morning meeting where we identify something — like what the weather is — so there’s spatial awareness getting their interest. My students are very interested in animals, so I often gain their interest in learning through animals. Then, I do a whole-class lesson. Today we described images. We looked at three different images, and we talked about who was in the picture, and what they’re doing, and what time of day, what season they are in… other days, we do story time, and then we break off into small groups to do work specific to the story.

For my non-homeroom class, we do individualized work in groups. I might work with three students and do a story with them while other students are working with Ms. Williams. Sometimes we have additional support, because it’s very individualized. The ability to listen as a whole group is just not there, so there is more disruption internally for me and externally for the students. They’re very sensory-oriented, so if one student does not like what I’m doing and is loud, that can trigger or stimulate another student. It’s a big snowball effect.

I am considered one of two lead teachers in my position. Mr. McGrain is my counterpart. I do English and Social Studies, and he does Science and Math. Then within both of our classes, we have paraprofessionals who are not assigned to any specific student. That’s Ms. Williams and Ms. Scott. They’re great, and they definitely help students who need one-on-one support.

Within the classrooms, there are students who have either an instructional support aide (someone to help with learning) or a behavioral support aide (someone who’s there to help by targeting behaviors). I have four students who have a one-on-one aide, and then within Mr. McGrain’s homeroom, he has three. There are a couple of students with significant individual needs who would benefit from a one-on-one but don’t have one yet.

I take work home every day. I’ll work out or hang out with my dog, but then after dinner, I work for two hours every day. Even though I have a planning period, there’s not enough time in the day.

Four-day school weeks for students and five-day work weeks for teachers would make life ideal. It would create a better personal life for me, and a more supportive, encouraging environment that’s manageable.

When I started through City Teaching Alliance, my first coach asked why I wanted to become a teacher, and I asked why he left teaching and became a coach. He told me, ‘I couldn’t be a good father and a good teacher.’ I was really angry about that then. Now that I want to have a baby in the next couple of years, I don’t know how they do it. I can barely even take care of my dog, because I’ve got to do work to help the students at school.

There has to be something that makes it not as consuming, because it’s super consuming and I can’t pay my bills. I can’t pay my student loans. I’ve got credit card debt because I need to put my groceries on my credit card bill. I’m trying to save for retirement, so that takes 75 bucks from my paycheck each week.

If I stay teaching forever, I want to be able to eat and retire. That would be good.

When I was in college, I was applying to different jobs, and I applied to Special Olympics Connecticut. I was really interested. My dad called me and asked, ‘Why didn’t you tell me you were applying?’ We would have had to go through lawyers because of my dad’s position. The Department of Developmental Services helps fund the Special Olympics in Connecticut, so no one wanted it to look like my dad was paying for me to get a job — especially me.

I ended up moving away from Connecticut instead. I found this program where you get dual certification, and I had two family friends who had done this program as well; one who got placed in Baltimore and then one who got placed in DC. I ended up getting accepted, so I left Connecticut.

When I was in college, I thought about law school. I thought about policy work and going into the government, but I knew my dad started in the group home doing night shifts, working overtime, feeding people dinner… he started on the ground floor, and now he’s leading Connecticut. I’m proud of him.

If I want to one day do policy work, if I want to one day be an advocate, I need to start on the ground level of being a teacher. I believe, through and through, that education is the only system that touches everyone in America.

Secretary Cardona got nominated from Connecticut. He’s another person who started on the ground level. He started teaching in the school district that he attended as a student, and then he became a principal, became superintendent, became Commissioner for the Board of Education in Connecticut, and then became the Secretary of Education.

While I have no desire to make it that far, if I want to be a leader in my own school, I need to know what and who I’m leading. That reinforces my desire to teach every day.

–Winona Scheff

Teacher in Baltimore City Public Schools

City Teaching Alliance Fellow, Cohort 2021

Baltimore, Maryland