My mom was an elementary school teacher, but I had no interest in teaching when I was growing up. I told everybody that I was going to be President of the United States, and that was my plan from when I was about four years old!

I studied in Washington, D.C. at American University and majored in political science, and in college, that was still my plan. I even interned at the White House while I was an undergraduate. The first time I really considered moving in a different direction was around that same time. I tutored at an afterschool program in Southeast D.C. and absolutely loved the experience. It was a wake-up call for me because, as exciting as it was to be a 19-year-old working at the White House, I enjoyed tutoring even more. I found it more rewarding and fulfilling, and it was simply more fun. That was the first time I really began to rethink my career path.

I thought, ‘Well, let me consider teaching.’ It worked out pretty well that the master’s program our school offered allowed me to start taking some graduate-level education courses, and some of the courses I was taking for my major counted towards the social studies certification. I started working toward that when I was a senior, and I was able to complete my Master’s in Teaching with a certification in Social Studies.

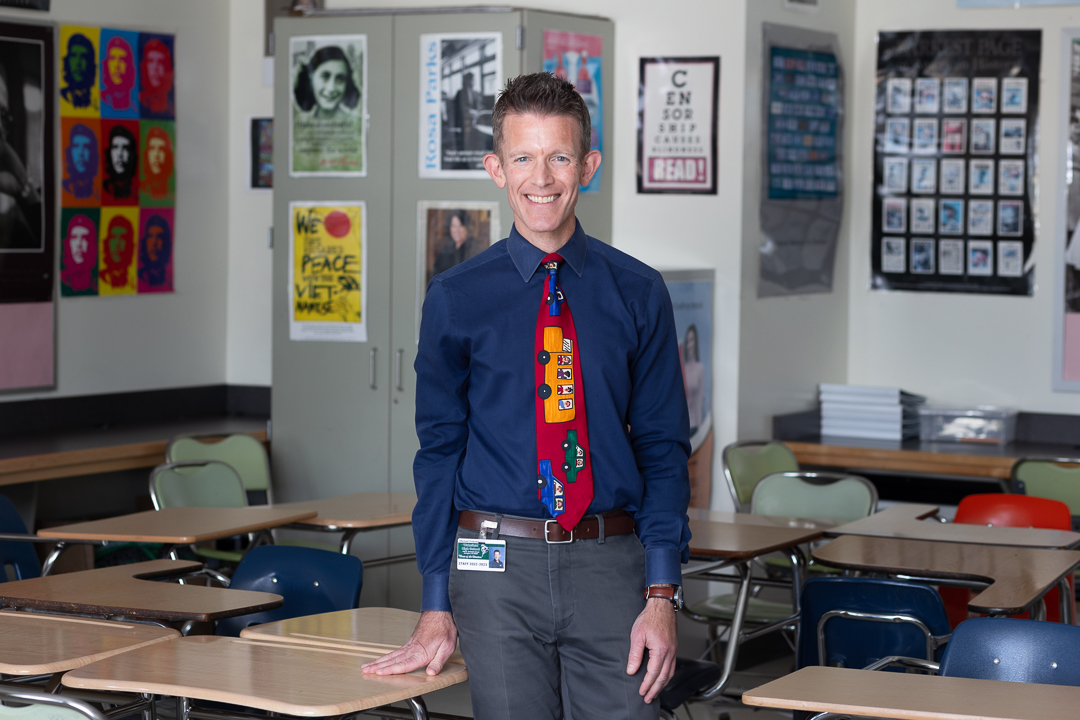

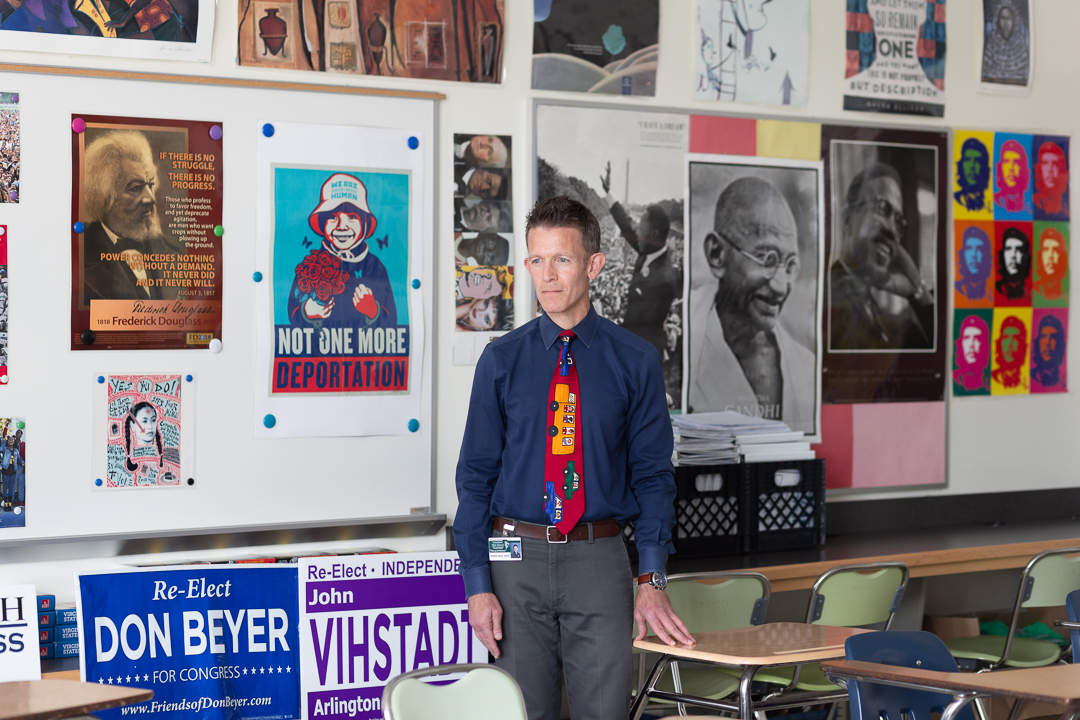

I always loved the D.C. area (still do!) and knew I wanted to stay. My first job offer was at Yorktown High School here in Arlington. I was there for 20 years, and I’ve been at Wakefield High School for the past eight. I can vividly remember the first class I ever taught on the first day of school. It was 3rd period, 9th grade World History, 45 minutes. By the end of that class period, I knew I was set. It was one of those lightbulb moments, and I never looked back. I was barely 23 at the time, just a few years older than the kids I was teaching, but I knew right then that teaching was something I was destined to do.

What initially drew me to teaching was my interest in public service and wanting to make a difference in the world. You can see the difference you are making in the moment. I think that’s what drew me in, and that’s what kept me in even when it was difficult. Being surrounded by the kids also gives energy to my extroverted self.

When I was tutoring, the community we served was, in many ways, so isolated. This different part of the city was a whole different world, and it angered me. They were surrounded by adults who wanted to support them as much as possible, but it was a stark difference in resources from what I experienced growing up and what I saw in the surrounding area.

The D.C. area is still very much divided along those lines. These children have some of the greatest needs, and that fired me up to see how I, as a teacher, could address this.

Today, we’re surrounded by an agenda driven by those who already have privilege, not by the people who need the most help and deserve a voice.

I think a lot about what it means to be a social studies teacher. I hope what I teach and the way I teach inspires kids to take an interest in the world around them, to care about what’s happening in other parts of society, and to get involved in their community. We have a responsibility to take an interest in each other and to care about what’s happening in the world around us. If we’re lucky enough to be in a position to change it for the better, then that’s what we should be doing, in whatever capacity we end up in; as a writer, artist, doctor, judge, activist, whatever it is. We all have this obligation to serve others.

Several years ago, I set up a panel discussion with some of my former students. These were all kids I had taught, now doing something in public service, something that involves changing society for the better. I want the students I’m teaching now to see what they’re capable of accomplishing in the future.

There have been moments in my teaching career where the need to talk about broader implications of the curriculum has been a moral necessity. The big one for me was being in the classroom on September 11th.

I remember we were instructed to turn the TVs off. It was so overwhelming, but I didn’t want to go back to the routine because that just felt off.

I told the kids, ‘I want to give you a space where you can ask any questions you have, and I will do my best to answer them. If there’s something you need to talk about or to get off your chest, this is the space for that.’

Another moment was the 2016 presidential election. A lot of my students were very recent immigrants. Coming into the classroom the morning after was somewhat surprising because I thought it would be a really tough day for them; I realized that they’d already been through much worse, more traumatic experiences in their own lives. I always kind of knew, as a teacher, that my role in their life is a small fraction of everything else, and what they bring to the classroom shapes them so much more than what I share with them. It was a realization that this is their experience and I have to honor that too.

The whole dynamic of teaching virtually and then hybrid during COVID felt a lot like that year after 9/11. We’d been through this traumatic experience together, and I felt like we bonded because of that. It made it harder to let go.

I’ve always been the kind of teacher who believes it’s really important to build that classroom community. and I usually get a little teary-eyed at graduation. Some of the kids I never even met in person, yet I felt more connected to them.

There were moments when I could see what we were doing in the classroom transcending into what was happening in the world around us. Especially teaching something like social studies, you want the students to see its importance and how it connects to their lives and the wider world. I see teaching as essential to democracy because we’re educating our fellow citizens of the world. It’s a privilege to be together in a space where they can see their similarities, explore their differences, and understand our common humanity.

People who don’t teach, and even some teachers, don’t always realize the impact you have on kids. Not every student will write you a card for Teacher Appreciation Week, but many come away from the classroom with a sense of what the environment meant to them. I keep going back to that idea of community.

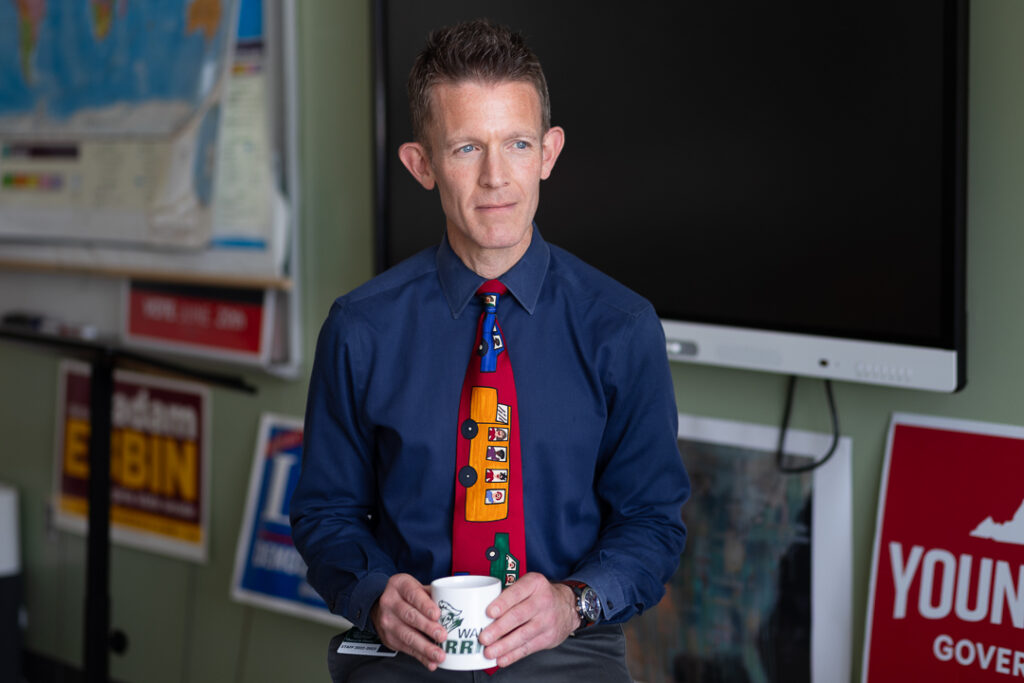

One of my favorite activities is our Friday discussion where I choose a news article, or the students would select an article, and we would spend period sharing our thoughts and connecting the article back to what we’re studying. One of my goals as a teacher is to encourage that kind of civic dialogue. I feel like the kids, whatever their opinions are, feel comfortable expressing them. My class is a place where students can hear a range of perspectives. We don’t do that as a larger society, or at least we stopped doing it, but I think that’s essential to making progress on any issue.

My class looks at examples in history where civic engagement worked, where it didn’t work, what made it effective, what strategies and tools were used to make progress and affect change, what challenges they faced, when they felt overwhelmed, what odds were stacked against them, and what they did to overcome them.

I’ve been teaching for a long time and I’ve yet to have a school year where I’m not super excited to go back. I start having my back-to-school dreams in late July or early August, and that’s a sign that I’m ready to dive back into it.

I’ve never been bored. I’ve taught many of the same subjects, but it feels different every year. It’s even different every class period, partly because of the people who are in the room. For example, I recently taught a student who was Palestinian, and she shared her family’s experiences as refugees. It became a powerful moment where the student felt comfortable enough to share her personal story, shaping our discussion about a historical issue and contemporary geopolitical question.

I feel like K-12 education is often seen as the go-to punching bag for the ills of society. Somehow, I’ve managed to maintain a positive attitude despite that. I do feel like it’s starting to get worse in many ways. The people who criticize teachers outside of schools don’t always realize how detrimental that is to the broader project of public education.

I think I’m lucky to work in a community where people value teachers, taxpayers support public education, and parents are very active and supportive of what we’re doing in the classroom.

My colleagues and I watch Abbott Elementary. I love it and it’s dead-on! One episode that really got to me was when Gregory won Teacher of the Year. He used it as an opportunity to elevate his colleagues and talk about how much they support him. That’s something that has made a big difference for me, both when I was a newer teacher and had mentors guiding me, and now as a more experienced educator collaborating with younger teachers. I see the fire in their eyes and it motivates me to challenge myself professionally.

Teaching can be a very humbling endeavor. I have a lot of experience, but I’m still learning, and having supportive colleagues pushes me to become a better teacher.

I think having school leaders who are not only competent, but also have a larger vision for what school is about and the importance of public education makes a big difference.

I’ve always enjoyed collaborating with other teachers and seeking out professional development opportunities, both as a participant and a facilitator.

I always try to do some sort of professional development during the summer. It gives me the opportunity to talk to other teachers who care about the same things that I do. I always feel pretty fired up after those experiences, not only because of what I can bring back into the classroom for my students, but also because it’s inspiring to know there are many people out there who share a similar vision.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about wanting to give teachers greater agency. This is what frustrates many teachers; so much of what we’re expected to do is a top-down mandate. That’s sometimes counterproductive because we’re professionals and should be trusted as such. Some of the best professional development I’ve ever had involved walking down the hall to another teacher and asking, ‘Hey, how would you handle this situation?’

I want teachers to see ourselves as having a voice, even outside the classroom, including in policymaking. Teachers could play an important role and should be given that power and voice because most of us are really trying to do some good and are in the ideal position to inform others about what our schools and students need.

I also wish more people valued how much young people have to offer. Last year, I was part of a committee responsible for hiring new teachers. I suggested that we also include some students to be part of the interview process. Their insights were, in many ways, the most perceptive in that room. Many people, and sometimes even teachers ourselves, don’t understand the value that a lot of kids are bringing into the classroom and to their schools.

The Hollywood version of school is that a teacher comes in and transforms the lives of their students and they become different people because of this one person. I don’t necessarily want students to feel like it was me who changed them; I want them to change themselves.

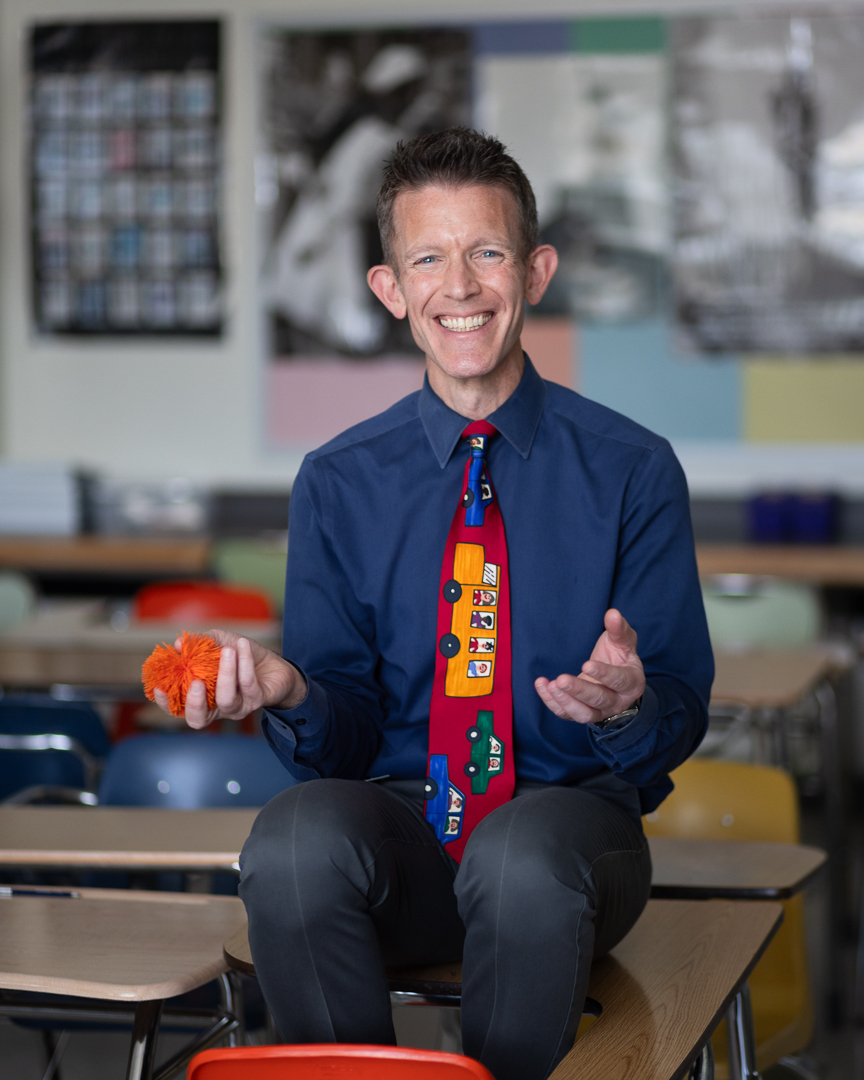

Teaching isn’t about passing along information or wisdom that I’ve collected and am now bestowing upon the future leaders of the country. My role is more to give them a space where they can see that in themselves. Real teaching is about encouraging students to bring out their own potential.

I try to connect history to their real-life experiences. I’ll give them a reading and show them a clip about the first student sit-ins and their nonviolent strategy, and how they prepared for their protest and had contingency plans. I walk them through that and then connect it to our class. I want my students to not only put themselves in the shoes of other people throughout history, but also see how those experiences might connect to their own lives.

A couple of days after the mass shooting at Parkland, some of my students organized a walkout. It was huge, with probably at least 1,000 kids walking out of the school. It goes back to what I was saying about not giving kids enough credit; they had their strategy, they planned it, they knew they were going to attract media attention, they organized their speakers, they had their signs ready to go, and they had their message.

I mentioned to them that voter registration was also scheduled for that day. They led this walkout, this incredible social movement of nonviolent civil disobedience, and then they came back into the school and got themselves registered to vote. It was a powerful moment where the students took the initiative and made a real difference.

Two weeks ago, I was accepted into a National Endowment for the Humanities summer program for educators. They run these incredible institutes for teachers. I applied to a program on school desegregation in Virginia called The Long Road from Brown, which ties in perfectly with what I teach.

When I received the acceptance email, I was thrilled, but just two days later, the federal government eliminated all NEH funding. Every teacher program was canceled, along with funding for museums, libraries, and even the archaeological dig at Jamestown.

These programs represent a tiny fraction of the federal budget, but cutting them wiped out opportunities for teachers across the country; people who rely on them to grow as educators and better serve their students.

It’s been hard to process the disappointment and the anger. Not just because this opportunity was taken away, but because of what it signals about the direction we’re heading as a country and what it means for teachers, students, and public education as a whole.

This conversation with you came at a good time. It reminded me that I still have a voice and that I can use it to help reshape the narrative. I really appreciate that.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about my role outside the classroom. Over the past few years, I’ve become deeply involved at my kids’ elementary school. It’s become another way to stay grounded and engaged, especially at a time when everything I stand for as an educator, a parent, and a community member feels like it’s under attack.

I’ve kept in close touch with teachers from all over the country who I’ve met through various professional development programs over the past twenty years. I’m close with the group of educators who were AP readers with me last summer for the new African American Studies course, and I still talk to many of the teachers from a program on the Civil Rights movement I did in Alabama almost a decade ago. I’ve also done a lot of work with the SEED program, which stands for Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity and offers trainings nationwide.

It becomes a teacher community and we often share ideas. Whenever a group of teachers gets together, the conversation inevitably turns to, ‘Here’s how I taught this,’ or ‘Here’s a great lesson idea,’ or ‘Can you show me what you did for that unit?’

Especially now, that kind of community feels more important than ever. Knowing that there are still educators out there who are trying to do the right thing, pushing back against efforts to limit what we can teach or even talk about in the classroom, and finding ways to support students through all of this? That gives me hope.

And look, I know I speak from a place of privilege and what I’m experiencing is just one small piece of a much bigger puzzle. What keeps me up at night is worrying about my students who might be undocumented or those who are transgender. What could happen to them? What could happen to their families?

Even my own kids’ classmates, many of them are being directly threatened right now.

I think for most social studies teachers, any opportunity to make a direct connection between the curriculum and your students’ lived experiences is incredibly valuable.

I teach in Arlington, which was the first school district in Virginia to desegregate, although it still took several years after Brown v. Board of Education to actually do it, and decades more to complete the process. So we’re not just talking about history in a textbook, we’re talking about our own community.

I have a student right now whose grandfather was the first African American to play on our school’s basketball team. He attended right around the time desegregation efforts finally began. In my classes, we’ve had real conversations about that long process toward desegregation and whether we’ve ever reached the ideal of full integration.

One of my lessons with students involves examining demographic data about our own community. They realize how some schools are still over 70% one race or another. We look at suspension rates and free and reduced lunch numbers and compare them between elementary schools. Even in a place as diverse and progressive as our district, there are still deep divides, decades after the fact.

We also talk about how some of the first student sit-ins happened just blocks from where they go to school. I ask them what that means to them. How does that connect to what’s happening in the world today? And what power do they have to make a difference?

All of that is relevant, but I think that’s what scares a lot of teachers. The idea that drawing parallels between past and present might get you into trouble; that you can’t even connect the dots when they’re clearly visible.

I had a student years ago who had moved here from China. She once told me that the difference between my class and her history classes back home was, ‘You give us information, and then you let us come to our own conclusions. In China, they just give us conclusions!’

That’s always stayed with me. I’m not partisan in class discussions. I never tell students who I vote for. But I do believe young people deserve a full and accurate picture of what happened 250 years ago and what’s happening today. Then they get to decide what it means.

That’s what teaching is all about: giving students access to knowledge, context, and perspective. Helping them understand their communities, their country, and the world around them. And maybe, just maybe, encouraging them to use that understanding to do some good and to make change when they see something that’s not right.

I observed a somewhat muted reaction from students after the election in November, but now I’m seeing an increase in anxiety. I think that’s partly because I teach students who are being directly impacted by what’s happening, not just in terms of what we’re allowed to discuss in the classroom, but in their everyday lives.

I have students who are war refugees from Ukraine, and they’re worried about how recent policy decisions might affect them and their families. My own children attend a school where parents have been apprehended by ICE. Just a few weeks ago, ICE agents were staking out the public library across the street from where families pick up their children after school.

That level of threat; children are feeling it. Little kids. My daughter is in second grade, and she came home one day and told me, ‘These men chased one of my friends and her family, but they got away. They were trying to send her dad back to her country, but I think she’s okay. She was born here.’

A seven-year-old should not have to process that kind of fear, but that’s the world we’re living in right now. And I think more and more people, students and adults, are starting to realize the real-life implications of what’s going on.

The classroom has to be a space where students can talk about this. I’m not trying to be political, but right now, it feels like even critical thinking has become a political act. The idea that a student might take what they’ve learned in class and use it to influence policy in their own community? That’s now considered controversial.

It used to be that registering students to vote was a natural part of their civic education. Honestly, one of my favorite days of the year is when we register kids to vote. The fact that even that can be seen as controversial now is deeply problematic.

Looking at what’s happening in the world and drawing connections to the past? That’s part of my job. I have a responsibility to help students do that. I’m not force-feeding them a belief system. I’m exposing them to what actually happened and the world we live in today.

Many of us who teach history have leaned into primary documents. I’ve even heard this approach encouraged by some of my supervisors. Sharing a primary source in class isn’t about telling students what to think. It’s about giving them the tools to understand the past and use that understanding to navigate the present and the future.

That’s what I try to do every day. In my daily warmup, we always begin class by discussing events that happened ‘on this day in history,’ and I share with them the front page of The Washington Post. We talk about the connections between what happened in the past, what we’re studying in class, and what they’re seeing in the news right now.

And more often than not, they’re the ones making those connections. But they need the space and the support to do it. Otherwise, what are they really getting out of their education?

One of the things I think a lot about is how to balance what’s considered ‘political’ and what’s simply responsible teaching.

I’ve had students ask me who I vote for, and I make it a point not to share that. I never have. I wouldn’t want any young person to feel like I’m trying to influence how they should vote or what they should believe.

But I do make one thing clear, especially for students who have come from other countries. ‘I’m happy that you’re here. I’m grateful to be your teacher. Your presence in this classroom makes our school and this country a better place.’

Now, somehow, even saying that might be considered political, but it shouldn’t be.

Teachers have a responsibility to welcome all students. We need to show them that they matter, no matter their background or identity. That’s the essential first step, and it’s what makes meaningful learning possible.

We also try to help students make connections. For example, my World History class is going on a field trip to the Holocaust Museum soon. We’ve talked about how, in Nazi Germany, one of the first things the regime did was strip people of their citizenship, deny them a place in the public sphere, and eventually, deny their humanity.

And then we look at where we see that happening in the world today, including in our own country.

A few weeks ago, we were discussing President Roosevelt’s Executive Order that created internment camps for Japanese-Americans. Students brought up the parallels between what happened then and what’s happening now.

When we learned about the definition of genocide, my students brought up current examples around the world that matched the textbook criteria. These are hard conversations, but they matter. I’m not telling them what to think. I just want them to think, to ask questions, to consider, and to understand.

The pace of what’s happening in the world right now is overwhelming, even for adults. Helping students process it is part of the job.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of civil society; not just civic engagement, but the very structures that hold communities together.

All over the world, when a leader wants to move toward authoritarianism, one of the first things they do, aside from attacking democracy directly, is target civil society. They dismantle the groups and institutions that allow people to connect, organize, and support each other. It’s what happened in Russia 25 years ago. Shutting down the community spaces that allow people to mobilize. Isolating them. Making them feel hopeless.

That’s why I believe so deeply in the idea of ‘teachers in their power.’ Yes, I want to do good work in the classroom, but I don’t want it to stop there.

I want my students and my colleagues to take the ideals we talk about in school and use them to make our communities, our country, and our world better.

I’m active in our PTA, and that’s part of why my work with other parents matters so much to me. I’ve built strong connections there, and many of them are just as frustrated and concerned as I am. They all care deeply about public education and are willing to fight for its survival.

The idea that something can be public, that it can benefit everyone, no matter who they are or where they come from; that idea is under threat. And it’s one I’ve dedicated my life to, not just as a professional, but as a person.

I believe we have a responsibility to one another and to the institutions that serve our communities. We need to use the power we do have to help others, to make things better, and to keep pushing the boulder up the hill, even when it might seem impossible.

At my own children’s school, we have a partnership with the Kennedy Center. There’s concern now about whether that’s going to survive. We’re a Spanish immersion school, and the whole point of the program is to embrace diversity; to celebrate what every family brings to the table. That kind of program is at risk, too.

After the last election, we saw incidents of students using racist language, even in elementary school. That led to important conversations with staff and with other parents. How do we respond? How do we talk to our children about race and racism, even at a young age?

That’s not just a teacher’s job. Parents have a role to play, too. That’s why I recently led a workshop for parents on how to talk to kids about race. That dialogue has to start at a young age.

We’ve also had ongoing conversations about how to support the families in our community who may be more vulnerable. These aren’t abstract issues. These are our neighbors and our friends. These are the parents of the kids our own childrexn invite to their birthday parties.

We’re trying to hold onto community, and that very idea is under attack.

But we have to hold onto it. We have to uplift it. We have to stand together.

That’s what keeps me hopeful. I meet so many people, every single day, who aren’t okay with what’s happening. And I believe that most people, regardless of their political stance, want to protect their children. They want their kids to learn in a space where books, ideas, and perspectives aren’t censored.

I work with colleagues who still feel a deep sense of responsibility to teach the whole truth, the unvarnished truth, about our history, flaws and all. Not to push an agenda, but to make sure that all voices are heard, those from today and those from our past. And I meet parents who want that kind of education for their children.

That way, students aren’t just learning one version of history. And hopefully, they’ll understand how those forces shape the world today, and maybe even find inspiration to help shape what comes next.

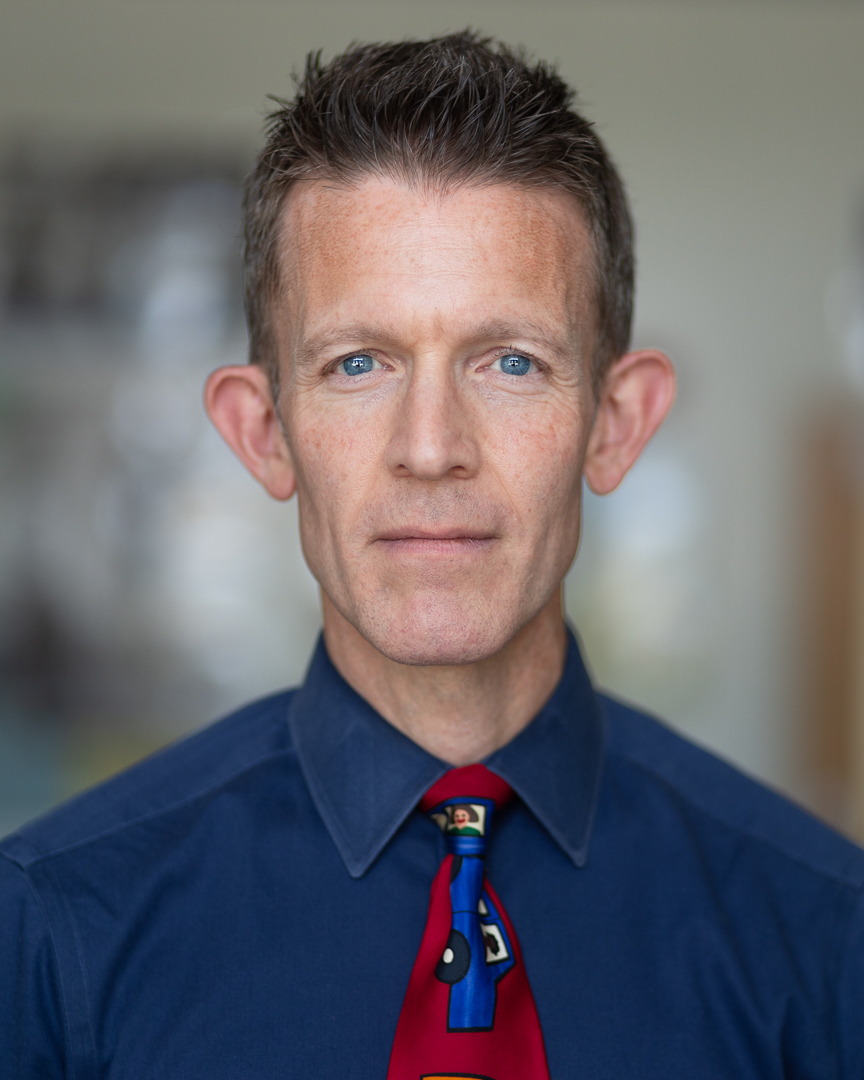

–Michael Palermo

Teacher in Arlington Public Schools

Arlington, VA