I grew up in San Francisco. My dad was a lawyer. I was told in school that I was good at debating and arguing with people, and I decided that’s what I was gonna be: a lawyer. So for the first three years of college, everything I did was to become a lawyer.

Between my junior and senior year, I needed to make some money, so I taught an SAT class. I realized that I really enjoyed working with the kids, because so much of it was about getting to know people and helping them go from one point of understanding to another. That lived in my brain for a bit.

I decided I didn’t want to go to law school. I started working for the college newspaper as a sports writer, and for a while I wanted to be a sports journalist. After I graduated, I took my shot at that. I interned for WebMD, writing articles about sports medicine. Then Little League Baseball’s online registration company moved me out to Boston. This was circa 2000, during the .com boom, so they were swimming in money. They even let me move my friends out there with me. They had a batting cage next to my cubicle. This was obviously not responsible fiscal management. They eventually went bust.

I was given six months’ severance, which was amazing for someone who was 24 years old. I had a lot of time to think about what I wanted to do. I was living in Boston, and I decided, ‘I want to go back home. I don’t want to stay in this field.’ Because there had been many days where I would go to work, and I could essentially hide out in my cubicle. I would get paid, which was cool for a 20-something-year-old, but compared to the work I did in college teaching and working for the paper where you had to be ‘on’ and contribute something every day, this felt unsatisfying.

My brother came to visit me while I was collecting severance. There was a job fair for nonprofits and education, and I told my brother, ‘That seems really interesting.’ He said, ‘Oh, that’s a do-gooder festival.’

I realized, ‘Oh. I think I want to be a do-gooder.’

I moved back to California. There were all these stories about how they needed teachers, and then I got there and realized how hard it is to become a teacher. I couldn’t just go into a classroom. So I did a year of AmeriCorps. I got hooked up with the Sunset Neighborhood Beacon Center. I was teaching computer classes, and I told the person I was working for that I wanted to get my teaching credential. He said, ‘I can hook you up,’ because he was the afterschool coordinator here at A.P. Giannini. And so I did some volunteer teaching in a math class, where the long-term sub was more than happy to let me take a third of her students in a challenging class.

It was so rewarding, working with the kids. But I still didn’t get a classroom job. I went into a credentialing program, and I got hired by the Beacon Center to be an afterschool coordinator at the elementary school near here. That was probably the best thing that could have happened to me as a teacher, because when you work after school, you don’t have grades as something that you can use as a motivating tool. You really have to build relationships. I always tell my students, a lot of what teaching is — and a lot of what government is — is figuring out ways to motivate people to inconvenience themselves for a greater good.

My wife started working as a public defender in Solano County. I had my credential at that point, and I contacted my master teacher at A.P. Giannini to ask for a letter of rec. He said, ‘I can do you one better. There’s an opening here.’

I was moving to Vallejo, which is an hour and a half away from A.P. Giannini. But at the same time, during my 5 years in this neighborhood, I felt like I was building relationships here. So I thought, ‘Well, worst-case scenario, I commute a year, I get good recommendations, and I get a job wherever I need to go.’

But I fell in love with working here. And luckily, in a weird way, my wife got laid off — because the next bubble burst. This was 2008. She got a job working for the State Public Defender in San Francisco. I ended up moving closer (to Oakland, not San Francisco, because it’s too darn expensive for native San Franciscans to actually live in San Francisco). I’ve been here ever since.

This school is in the Outer Sunset, and there’s a big Asian American population here. I’m Asian American, but I grew up feeling like an outsider to the Asian American community here, because my parents didn’t immigrate here from China. They emigrated from a Dutch colony in South America. We don’t speak the main dialect here in San Francisco, which is Cantonese. We speak Hakka. I didn’t necessarily have that same connection to China that my peers growing up did.

Working and serving this community, in a weird way, I feel like I finally have that connection with the broader Asian American community. A lot of the kids now are second and third generation kids whose lived experience is actually a lot more like my lived experience in the ’80s and ’90s.

My wife is Caucasian, so my daughter is mixed. And it’s nice now that I finally feel like I can confidently show her that there’s this community that’s part of her identity as well. She visits campus from Oakland if she doesn’t have school, and we have dim sum and browse the shops in the Outer Sunset. I’ve been working in this community long enough that folks on the street or in the stores occasionally recognize me and say hi. Given that I felt like an outsider growing up, sharing those experiences with my daughter is especially meaningful to me.

When I was running the afterschool program, we started a girls’ sports club. I was a jock in high school, I ran track in college, and I had a particular vision of how you get good at sports. The whole point of this girls’ sports club, which was funded through a grant, was to make it less intimidating for girls to play. It was to let girls be front and center. And I remember that I was pretty good at teaching, biomechanically, how to throw a ball. Having been an athlete myself, I was able to do that technical breakdown part. But the part where I had a lot to learn was the different perspective of these elementary school girls and their entry point into learning sports.

A lot of it was acknowledging how they felt in everything that they were doing. I always had to remember to ask, ‘How does this feel? What is intimidating about this?’ There were some great moments where I would mess up and they would teach me how to be better.

We’d play baseball, and maybe for the 15th time I’d try to teach a kid to swing a particular way. And she just didn’t do it right. And I would compare the swing to something, like a dead duck, and not understand that it was going to hurt her feelings. I’d see her kind of implode, and then double down.

Her name was Jenny. I remember this very specifically. She was like, ‘You’re doing it wrong.’ She called me a doofus. And she stormed off. I said, ‘Yeah! Go to your class.’ And then I turned and I looked at the other girls. And they were like, ‘No, Mr. Ray. You handled it wrong.’ One of them walked up to me and confronted me and said, ‘That was messed up, Mr. Lie.’

The next day, I said, ‘Hey Jenny, let’s talk. I’m sorry. I messed up. I didn’t realize how much pressure I’m putting on you girls.’

I had to learn how to stop and realize their emotional experience as they’re learning, when I’m all wrapped up in the technical things.

The girl who confronted me and said it was messed up, I still keep in touch with her. She trusted me to be better. She’s similar to my daughter in some ways. So yeah, it’s the relationships that I build. I love it.

Another big moment in my teaching career was 2016, the day after the election. I teach eighth grade social studies, and I had been prepping the kids for how the Electoral College works.

We were all very secure that Trump wasn’t going to win. But I remember distinctly, one of my kids — her name was Izzy — telling me as she left class, ‘I’m nervous.’

I said, ‘Don’t worry about it. There’s no way he’s gonna win.’

Then we all went home, and there was that blue wall that he had to break. And you’re just seeing state after state after state drop. The kids in my school’s population were experiencing their parents freaking out.

I remember driving to work the next day on the Bay Bridge thinking, ‘What am I going to tell these kids? How am I going to explain this?’

I thought about one of my first college classes. They were talking about how the demographics of America were changing and how by some year — probably around now — America was going to be a majority minority country. I went to UC Irvine with a diverse population, and I remember everyone in the room reacting like, ‘Oh, that’s cool!’ And for some reason, that struck me as I was driving to work.

Because a majority minority country sounds good to me. But there are parts of the country where it’s scary to them. It’s not necessarily people who are evil. It’s people who are scared.

So that’s what I taught my kids that day. I asked them, ‘What do you feel?’ And most of them said fear. I asked them why, and they said it was because they didn’t know what was going to happen. They understood that their lived experience was different than their grandparents’ lived experience. They were worried that they were going to go back to a time their grandparents had told them about.

I told them about how, when I heard this country was going to be a majority minority country, I was excited — but there was probably someone in another part of the country who was scared, because whatever I’d gain from that change might feel like a loss to them. It wasn’t meant to validate what happened, but I think it helped my students get their bearings straight, during a time when the world felt like it was spinning too fast. It resonated.

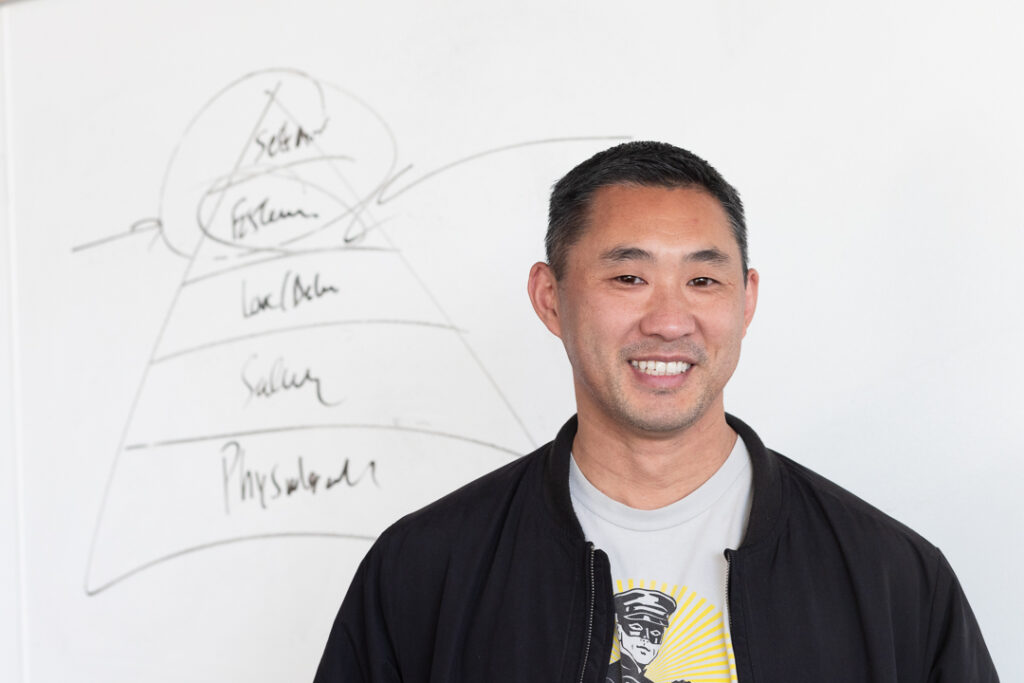

I always start the year off in social studies with the hierarchy of needs. Because what I want the kids to understand is that what we’re actually learning about is what motivates people to do things. The people we’re learning about from 200 or 300 years ago, they’re still people. And you’re a person driven by the same things that they were driven by.

It gets interesting and interactive when the kids realize it’s not that hard to put themselves in those historical shoes and start making informed value judgments or applying it to their own lives. Like at some point every year, the kids look at Hamilton and Burr dueling to the death as a social media beef over pride that spiraled out of control. It’s great when I scan the room and can see a few of the faces that have totally been there.

When the history doesn’t quite make sense, then those are the anomalies. But then those are the points where we can say, ‘Let’s research deeper. Why did that happen?’

All year, we always go back to the hierarchy of needs: what drives people to do things. We always point to it. I know that we often think of social studies in K-12 as focusing on what happened in the past, but I feel like in a broader sense, it’s about studying the human condition. It’s easy for 13-year-olds to dismiss how relevant remembering some names and dates from the past is to their lives, but when you frame social studies as learning about what makes people tick, it can be applied to their own day-to-day conflicts and aspirations.

Kids lean forward when you’re selling that kind of knowledge. And what’s funny is that kids come back years later, and that’s the one thing they remember: ‘Mr. Lie, the hierarchy of needs!’

I feel like there are three camps of people, in terms of public perceptions of teaching. There’s one camp that says, ‘Teaching is a terrible hurricane and I feel so bad for you.’ It’s like I work with toxic waste. ‘We understand that your job is vital to our society, but man, we feel so bad that you have to do it.’ Right? That’s one camp.

On the other end of the spectrum are people who say, ‘Oh, it must be so nice to have this super cushy, easy job.’ That’s the second camp.

But the third camp is the people who want to hear the story. They know that teaching can be both terrible and super fun, where Ray comes home with a smile on his face. They want to hear the stories and how you work through the challenges, and how your experience as a teacher is different from the experience that we had as students. That camp is the people who are closest to me. They respect what I do. They understand the value of what I do. And they’re curious.

That’s also part of why I love the job: I want to work in a field where I have something to say about my day when I come home from work. That’s so valuable to me.

I wish people weren’t trying to scare people off from entering the teaching profession. Yes, it’s challenging, but anything that’s good is also challenging. If there’s no risk, there’s no reward.

When I left the .com world, I remember telling myself, ‘I’m going to have to understand that I’m never going to own a BMW.’ I don’t really care that much about cars to begin with, so it wasn’t that hard. But I was still in my twenties, and I thought, ‘I have to be okay with the idea that other people are gonna judge me for not having certain things. Am I okay with that?’

If my daughter wanted to go into teaching, that’s the same question I would ask her. And I would ask her, ‘Are you willing to get to know people? Everybody? Not just the people you would gravitate to in your normal day-to-day experience?’

Because if you’re willing to stretch out of your comfort zone when it comes to really getting to know people, I can’t think of a more rewarding line of work.

I’ve never questioned staying in teaching. Not a moment. I always tell folks that if I won the lottery on a Sunday, I would go to work on Monday. I wouldn’t tell anybody, and I would just keep going to work… and probably make an anonymous donation to get my school working laptops and ergonomic furniture.

I have a colleague who is an amazing teacher. And in the last couple years, this person has questioned whether or not they want to stay in the profession. They tell me that what keeps them around is the relationships. They say, ‘I don’t want to let go of the rope. We’re both holding on to the rope, and I don’t want to let go.’

When teachers get burned out on teaching, it’s because we’re always short on time. The professional development we get pushed into focuses on a particular technique that someone has decided is going to fix everything, and oftentimes, it doesn’t take into account that teaching K-12 is a marathon. Because if I’m a college professor, I’ve got these students for maybe three months. When you teach K-12, you’ve got them for nine months. You’re having to balance and ride this wave of energy, and one technique is not going to be the thing that helps you do that.

Teachers want professional development that focuses on a more holistic approach to educating people. A broader approach like, ‘How do you install an inquiry-based classroom? How do you get the kids to be more curious?’ It’s not as sexy because you’re not necessarily going to see quick results.

Most teachers want to get better at this craft. We need more time.

Administrators want to be able to show that staff are working every second that they’re being paid. They need to be able to prove that teachers are filling that time. But so much of teaching is being a craftsperson, where you need to sit and be quiet and reflect. I actually appreciate my commute, because I have all this time to reflect, and I think it makes me a better teacher.

It’s actually a big part of my teaching process. I’ll drive and I’ll think about what went well and what didn’t go well: ‘How did I mess up today? Why did I do that? And how can I make it right?’

As a US history teacher, I worry that more and more people in our society are going to conflate being uncomfortable with being unsafe. I think that a lot of the problems that we run into in our society have to do with people not being open to being uncomfortable in order to learn something or understand something better.

I don’t want to discount emotional safety. But I do think there’s a danger in banning discomfort for the sake of safety. We confront things in my class that make people feel uncomfortable, for good reason. We talk about enslavement — that it was once legal for the ancestors of some of my students to own the ancestors of some of their peers. Students confronted with that fact should feel some sense of discomfort. It’s the teacher’s responsibility to explore challenging real-world topics in a way that accounts for students’ safety. And I worry that people with ulterior motives will censor challenging conversations about our country’s past under the guise of protecting emotional safety.

If we ever get to a point where getting kids out of their comfort zone is something that jeopardizes my job, that’s the one thing that might make me not want to do this anymore.

I’m tasked with helping kids understand American politics — things like the differences between Democrats and Republicans and their views on loaded topics like race and gender. I could play it safe and address challenging topics on autopilot, but I firmly believe that people gain deep understanding when they’re emotionally invested. So I try to weave in relevant current events or films to get students to feel something. The truth of the matter is I don’t always get it right, but luckily I’ve had kids who’ve held me accountable and were brave enough to give constructive criticism.

A few years ago, the students were growing numb to the issue of slavery. The fact is, slavery is embedded in every stage of early American history, and at some point the kids came to see it as a topic about numbers as opposed to people. I wanted them to confront how dehumanizing enslavement was, so I curated scenes from 12 Years of Slave. It’s an intense film, so I figured out how network TV censored particularly graphic scenes and I did the same. A lot of the kids I intended to get through to said, ‘I get it now. This is personal. This was about people.’

But there were African American kids who understood my intent, but felt like I was using their historical trauma as a teaching tool. One of them privately told me, ‘I get where you’re going with this, but that was uncomfortable. We already know that this happened to our ancestors, and it hits different for us than it does for the Asian or white kids in class.’

I asked this student what they thought would be a better approach, but they weren’t sure. It’s a lot to ask of a 14-year-old, so I shared my challenge with a friend who teaches at a university. He experienced the same feelings as a kid and asked me to count how often I presented African Americans as victims during the year vs. examples of Black achievement. It was an aha moment.

I brought it back to my students and they let me try a new approach. Recounting this episode is anxiety-inducing today, but I appreciate that the relationships we build in this room make it possible to grow from my missteps.

When you put the work into building relationships with the kids, there’s a point in the year when you suddenly feel like, ‘Oh, these are my kids. I’m theirs, and they’re mine.’

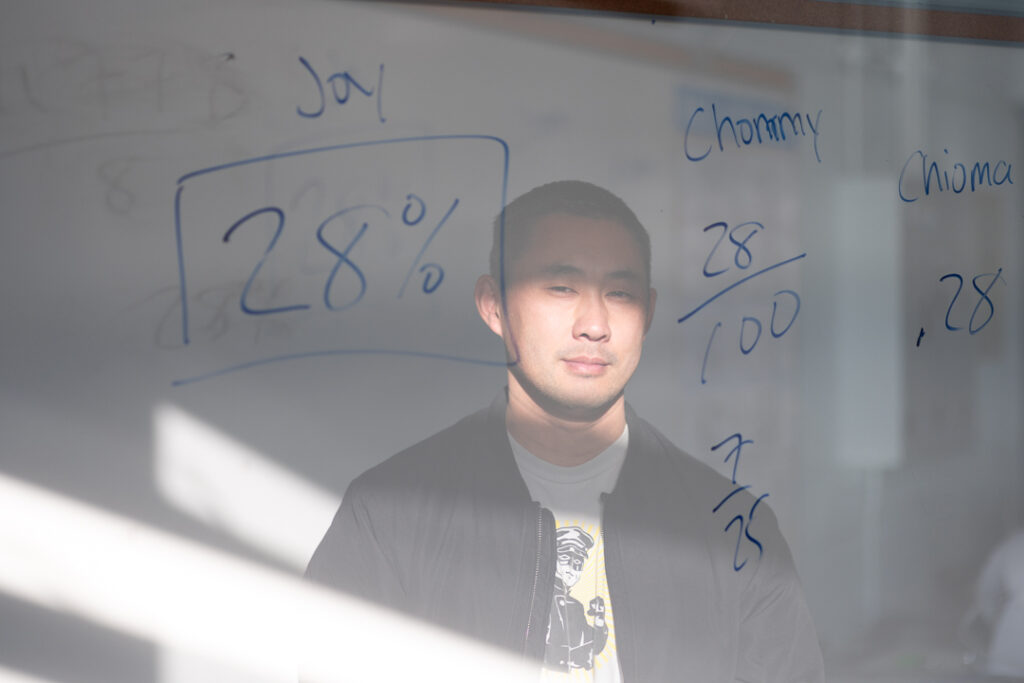

Like in my study skills class. Every week, the kids bring in questions and points of confusion from other classes. I’m credentialed in social studies, but for this class I have to basically pretend that I’m a 7th grader taking math, science, and ELA over and over again. Every year, the kids have similar math questions. Today it was the question about the differences between fractions, decimals, and percentages.

You see on the board where it says ‘28%, 28/100, and .28?’ Well, I have a kid in my class whose name is Joy. I taught her older brother, so I know her family a little more than her peers. So I asked, ‘Joy. Does your mom call you Joy at home?’ Kind of knowing what her response would be.

She said, ‘No. She calls me by my Nigerian name.’

I asked her if she wanted to share her Nigerian name and she said no. So I was like, ‘Okay, I have a Chinese name that I’m known by at home, and a Chinese nickname that I’m known by at home. And if you share yours, I’ll share mine. Okay?’

So she shares hers, and when she asks for mine I say, ‘I ain’t telling you!’ And we’re all cracking up. I tell her my three names. And say, ‘Here’s why I’m asking you this question. Because 28% is Joy. 28/100 is Chommy. And .28 is Chioma.’

And she was like, ‘They’re the same thing.’

I said, ‘Yeah, they’re the same thing, just expressed differently depending on the situation. Think about which name your mom uses when you’re in trouble and which one she uses when she’s happy with you.’

And she was like, ‘Oh my god!’ All the kids in the class were like, ‘Oh my god! We get it!’

It’s those kinds of moments that I wish people could see. When everything comes together. The kids and I are stretching ourselves, we’re building off each other, we laugh a little, and we end the day feeling a little more confident than we did when we started.

School can be amazing at every age when authentic relationships are built and adults earn the trust of the kids in the room.

–Raymond Lie

Social Studies & AVID Teacher at A.P. Giannini Middle School

San Francisco, California