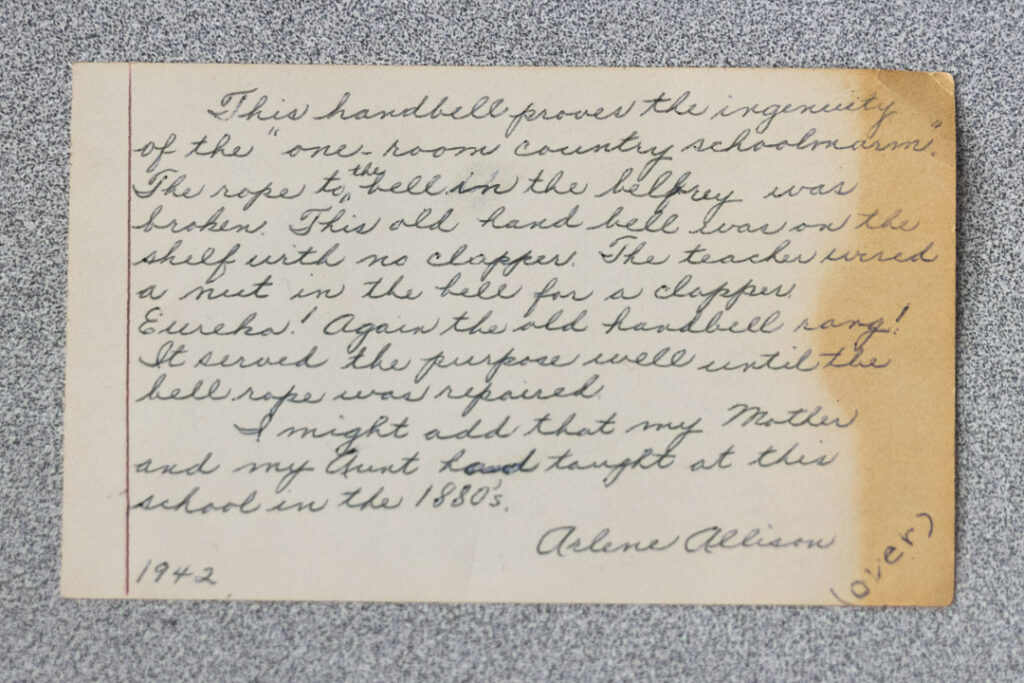

Teaching runs in my family. The bell was my grandma’s. She was the last teacher at a one room schoolhouse in Cold Spring, Wisconsin. Because she was the last teacher, they gave that bell to her. She wrote on that card that both her mother and her aunt also taught in that school.

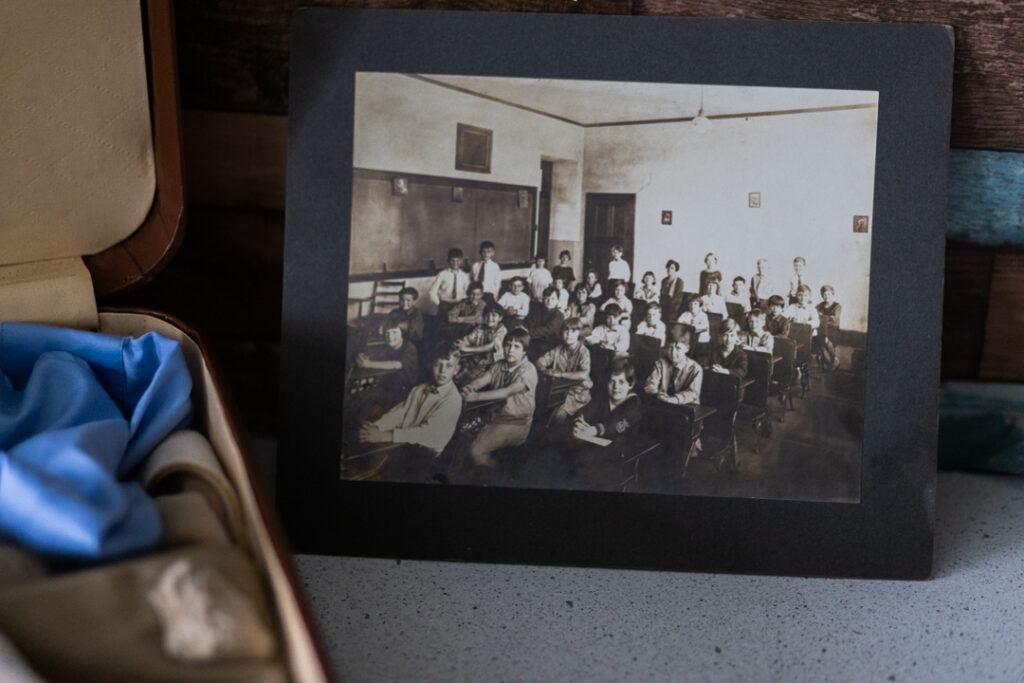

The picture is of my grandpa’s sister. She was a teacher for two years in Whitewater, Wisconsin, and that’s a picture of her in her classroom around 1935.

I brought these items in for the kids to see because we’re reading ‘Bud, Not Buddy’ right now in my class. It’s all about the Great Depression, and it helps them when I can bring in something with a personal connection. It makes it more relevant for them. I like bringing anything I can to make it a real experience for the kids. In the book, Bud has a suitcase with all his belongings in it, so I brought a suitcase too. I try to make it as exciting as I can and help them use their imaginations so that they want to keep reading the book. It’s working so far.

I have the kids bring in their own artifacts, too. One of the students brought in an old doll that she wanted to share. What that shows me is that they’re going home and talking to their families about what they’re learning, and then they’re making their own connections. That’s what I want for them — to be that excited about it. So if they ever want to bring anything in, they absolutely can do that. It makes them feel more invested.

When I was little, you never wanted to play school with me, because I always had to be the teacher. I would set up all my stuffed animals — they all had names of all the kids in my class. They all got report cards. I was that child.

My grandma had a big part in that because I spent a lot of time with her. She was a very good teacher, and she was passionate. She taught her entire life, which wasn’t always common back in those days.

Even when I worked at Dairy Queen in high school, I always wanted to train the new employees. I loved helping. I like explaining systems to people. And back then, I didn’t think, ‘Ooh, I’m mentoring someone on how to put a twirl on the top of an ice cream cone.’ But you know, it’s tough to start new anywhere. And I worked in college at Sentry Insurance, and I would develop different programs for new employees and come up with new ways to train them. I like creating things like that. I still really like mentoring the new teachers.

I taught first grade for the majority of my career — 14 years. Then I went to fifth grade, and I was there for several years. Then I did multi-age: third, fourth, and fifth. And now this is my fourth year in sixth grade. I always believe I’m where I’m meant to be at the time.

I’m passionate about the social-emotional aspect of learning with kids, and sixth graders really need you. They’re a hot mess. At this age, they don’t know what they need. And they really just need an adult who they can turn to, an adult who’s going to be there for them. And I can be that person.

Middle school was probably the worst time of my life. So more important to me than their reading or their writing is how they’re feeling. We need that balance for the kids, especially nowadays. For them to be able to learn, they need someone tending to them as a person.

My philosophy can be summed up with this quote: ‘We have to open the heart before we can open the mind.’ I feel very strongly about that.

Now that I’ve been doing this for 26 years, I get graduation announcements, invitations to graduation parties, and once in a while you get wedding invitations. I mean, for big parts of their life, they remember you. Some of them I had way back in first grade. And they still remember you and want you to come to those big days.

It reminds me that my time with them is a big part of their life. In middle school, it’s those moments when they will approach me and say, ‘Can I talk to you privately?’ When they’re coming to you as a trusted adult, to talk to you about something that they haven’t shared with anyone else. Or when they turn in an assignment and they share, ‘My parents are going through a divorce, and I don’t know what to do.’ It can be them questioning who they are — their identity. And that reminds me again and again why I’m here — because I can be that person right now for the students.

Every profession is important. But that’s why this is one of the most important professions there is. Because without teaching, there wouldn’t be other professions. We all need teachers to get to where we’re going.

Later in my career, I trained my dogs to become therapy dogs. My one dog, you could tell she was very special from the start. I had a principal at Rothschild Elementary who was very supportive of the idea. So I started bringing the dogs to school. The guidance counselor would take her, the principal would take her — she was with kids with anxiety, she was with kids who were in trouble.

Then we had a mass shooting in our community. There were five people who were killed. And I brought one of my dogs to school with me, because many, many kids were affected. The dogs can sense when things are wrong, and they just go to those kids. One of the students had lost a family member, and my dog stayed with that student all day. And every week after that, she would go with that student. And then every year on the anniversary, she would too.

After that happened, I presented at a statewide convention about how to introduce therapy dogs into schools. I feel like I must share this information with anyone who is interested because it’s truly magical to watch students respond to Izzy and Bella. It may be an instant smile with a morning hello or a pat with a goodbye. Other times, I watch in awe as students pet their ears and slowly forget they’re taking a test — or snuggle up and forget their fears or sadness.

When I first started teaching in the 90s, I didn’t walk into a classroom and think, ‘Okay, where are the safe spots in this room?’ I wasn’t constantly thinking about what I have to do if an intruder were to come into the building.

We are always the first line of defense for our kids, whether it’s a situation that is happening in the classroom with another student or something that’s happening externally. We are the first line of defense, and teachers take that very seriously. Never did I think that I would see something like this in my career. But I think we accept it. We’re still here. That’s just part of our job now. But it does add a lot.

We can’t open our windows. We can’t open doors. I’m glad our school is so vigilant about it, because it’s only silly until it happens to you. These kids are my responsibility. When I have them, they’re my responsibility.

You see that pink tape on the wall? That’s so I know where our fatal funnel is. So I know where to go with the kids.

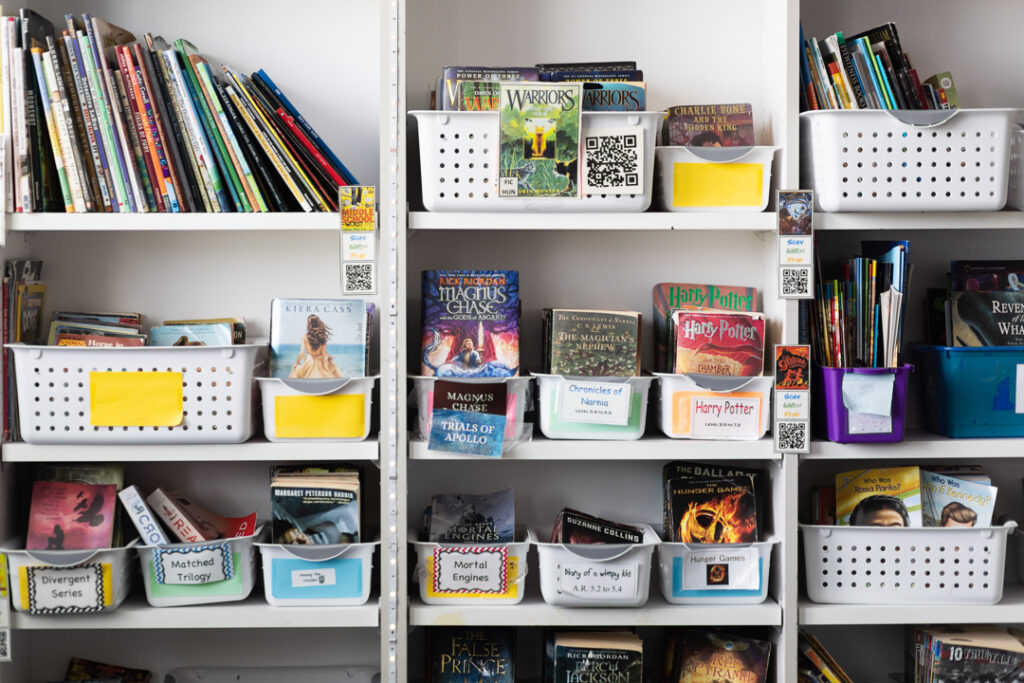

We don’t want kids to walk in the classroom and feel like they’re in a prison. So there’s a lot of money teachers put into work out of our own pockets. I could probably buy a small house with the money I’ve spent. I mean, all of these books. Bookshelves. Rubbermaid totes. Baskets, containers, crayons, school supplies. Anything to make the room more homey. We have to take everything down every summer too and then re-do the classroom before school starts again.

And if kids don’t have money for a field trip, we end up paying — because I am not going to let a student not go on a field trip. I always think, what would I hope that someone would do if it were my child?

So when teachers as a whole get criticized, we can tend to be sensitive. Because we worry about our students, and I think we do our best to always make things better.

We have a lot of conversations about teacher retention, enhancing the profession, and what we can do. Something I feel would help is if administrators were having more conversations with their high-quality teachers. And you can have conversations with all of your teachers, but especially those that you want to keep. Because if you’re reading the articles about teachers leaving the profession, if you’re paying attention to anything that teachers are sharing, you know there are problems that could have been fixed that could have kept them from leaving.

If you as an administrator know a teacher is going to leave, why not ask them why? Or say, ‘What would it take for you to stay?’ I’m sure that’s happening in some places. I think having those tough conversations is beneficial.

The other thing I think we need is more teacher voice and teacher leadership. I had a professor in college who said, ‘If you ever leave the classroom, you cannot be out of the classroom for more than five years. Because you will lose touch with what’s happening in the classroom.’ That was back in 1993. It’s still true, for sure. But look at our technology and how it’s changed. It’s got to be three years now — two or three years — and then you’re out of touch. So I feel that teachers have to be empowered to be decision makers and innovators.

I’m not saying that it’s not happening anywhere. However, a lot of times administration will seek input, but it won’t be used. It’s helpful to invite educators to take part in things that impact them, like instructional practices, your materials, the curriculum, the hiring of staff… but again, don’t just ask, truly listen. And then truly let their voices matter. Because when teachers are empowered, they’re going to take more ownership, and when they have more ownership, they’re going to be less likely to leave.

So I would say that’s a big one. The other thing that I’m a huge proponent of is surveys. I read about a district that surveys their teachers every other week. They ask, ‘How are you feeling about your work? Is there anything you’d like to share about how you’re feeling? What support or resources would make work easier for you?’ They ask three questions like that every two weeks — it’s quick and anyone can respond. And they have so much data. And of the people who didn’t respond, 56% of them ended up leaving at the end of the year anyway. Interesting. And for the ones who stayed, they have all of this actionable data.

It’s like with our kids. I do a quick check-in: ‘How are you feeling today? How did your week go?’ We all need a quick check-in.

The way I explain Love and Logic to people is that it’s very logical, but it’s not natural. It’s telling kids what you are going to do, rather than what they’re going to do. So it’s learning how to share control with kids, rather than being a drill sergeant or a helicopter.

A drill sergeant tells kids what they need to do — or else. A helicopter swoops in and does everything for the kids. Love and Logic teaches kids how to think for themselves by telling them what we are going to do, not what they should do.

A prime example is, ‘You are welcome to go to your next class as soon as you have everything picked up.’ Or, ‘I’ll be happy to continue as soon as it’s quiet.’ So again, it’s telling them what I’m going to do. I love leading the parenting class, because the parenting class gives me positive relationships with the parents.

Some of the biggest problems parents have are getting kids ready for school on time or getting them ready for bed. You need to make your child part of the process. I recommend parents start by having a conversation that starts with, ‘You know, we’re having trouble getting up in the morning. What do you think is going to help you get up?’ Of course the child will respond with, ‘I don’t know.’ Then the adult can respond with, ‘I have some ideas. Would you like to hear them?’

You never want to give your best answer first because children never like the first answer. So you need to come up with alternate options. Like, ‘Some kids want water dumped on them. How would that work?’ ‘Well, that’s not going to work.’ ‘Okay, good decision. Hmm. Some kids want you to walk in the room and turn on the light. How would that work?’ Come up with different things. But if you really wouldn’t be okay dumping water on them, then don’t give that option. I try to give children two (preferably three) choices in these situations. Because they have the control, nine times out of ten, they will get up.

I tell parents, rather than telling your child they have to dust, consider making a list of chores and letting them select one or two. Because they’re probably going to comply more if they have a little bit of skin in the game. (I still hate to dust, to this day, because my mom forced me.) It doesn’t matter if you’re two years old or if you’re 80 years old. Everyone wants control.

Drill sergeants will say, ‘No, they are going to do what I say when I say it.’ And I grew up with a drill sergeant. I listened to my dad. I did what he said when he said it. The problem is that kids who grow up doing exactly what they’re told have a difficult time making their own decisions later in life. And not just that, but when you learn to do what others tell you, you’re more easily influenced by peers too.

So we want to teach kids to think on their own, to become their own problem solvers, and then to deal with the consequences of their actions.

There’s a piece of advice that I love. It’s from the Cult of Pedagogy, and it’s called ‘find your marigold.’

It’s the one essential rule for new teachers: find the positive, supportive, energetic teacher in your school, because your growth early on depends on who you’re planting yourself next to. If you plant a marigold next to almost any vegetable, the vegetable will grow stronger — because the marigold protects the vegetable.

So the key is to find your marigold, because that person is going to protect and support you and help you to grow. And if you don’t find one, then you can’t stop looking. Keep looking in your school, or go somewhere else. Because there are marigolds everywhere. When you surround yourself with good people, you can do anything.

–Pam Gresser

ELA Teacher at D.C. Everest Middle School

Schofield, Wisconsin