My mother is a teacher. She is a wholehearted teacher. I grew up seeing her face light up with joy every time her students came up to her on the street: ‘Oh, hi, Miss, do you remember me? I was your student in fifth grade.’ She also taught students who were deaf, and they would greet her in Arabic sign language. That love and respect she was shown moved me because I realized her lasting impact on her students’ lives.

I noticed how her teaching was her life. Even during the pandemic, when all the schools in Egypt were closed, she found a way to help by tutoring children virtually. She was 74, and yet she didn’t want to stop helping children.

She taught me that teaching is a divine career and so, we, teachers, must be a role model for our students in order to be able to guide them to become the best version of themselves.

When I moved to the United States, I did not have a good experience in the airport. The immigration officer looked at me, and right away, they took me, even though all my papers were legal. They just took me to a room and started questioning me because I am from an Arabic-speaking country.

I was scared, and I was unable to understand what they wanted — even though I could understand English, I was so confused and tired. There was a cultural misunderstanding and some suspicion because they kept calling me by my last name, and I didn’t recognize it. In Egypt, in both formal and informal settings, we call each other by our first name.

That cultural misunderstanding caused me to stay there for three hours. I decided I wanted to become a teacher, not only to teach language but to teach cultural competence skills. If I had learned in my English classes that Americans sometimes call each other by their last name, I would have expected this. I wanted to become a bilingual teacher so newcomers wouldn’t find themselves in my place. I wanted to become a world languages and Arabic teacher to share my language and culture, and to help Americans understand the diversity of Arabic-speaking people and their cultures.

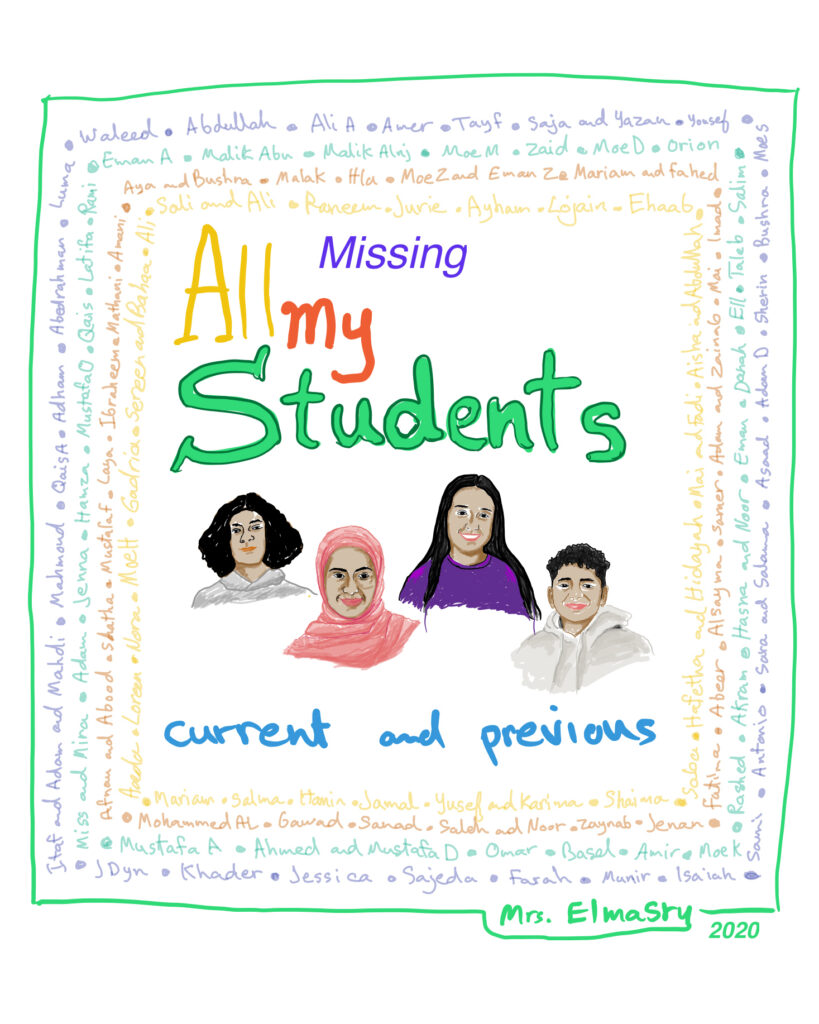

Sometimes former students come to visit me or send emails telling me what they’ve accomplished. In the middle of the pandemic, one of my students told me they got their auto mechanic license, one is finishing nursing, and one is in medical school. I am so proud of them.

This year, three of my students chose teaching as a career. It feels full circle.

I want people to understand that teachers are humans. We have families, and we understand parents’ struggles. We were also students before, and we understand where a student comes from. In my case, I understand how difficult it is to start a new life. I also taught myself English, so I’m aware of the challenges my students face trying to learn Arabic. I tell them, ‘If I was able to learn English by myself, then you definitely can learn Arabic,’ and they laugh.

Teachers have limited resources, and we probably want to do things that we can’t. The other thing is that many of the policies that parents don’t like aren’t put into place by teachers. I see many students and parents confusing classroom rules (set by teachers) and school policies (set by administrators) because teachers need to enforce the policies. It would be good if parents fully participated in the surveys schools usually send to collect their opinions before putting a policy into effect, so their concerns can be addressed.

Parents, don’t wait until the school calls to get the communication you need. I encourage parents to partner with teachers — especially if their kids are freshmen, because the first semester is very difficult, and freshmen might not talk to their parents about it. In elementary schools, we do a great job of that. We have classroom moms who we invite to read at storytime. But in secondary schools, we have a lot of social, emotional, and mental health needs with less parental presence. No one adult can handle this by themselves.

I really work to have a relationship with newcomer parents. Just sending emails will not work. They might not have an email address, and if they do, I’m not sure whether I should write in English or Arabic. They might be in the process of learning English, not aware of the terminology that we use, or unfamiliar with the education system in the USA. So I call them.

My school does a great job of encouraging families to be involved. At the beginning of the year, we host a Back to School Night, where all families are invited to walk their child’s schedule and meet with their teachers, counselors, coaches, and club sponsors. This helps put a face to the name they see on their child’s syllabus. We also host two parent-teacher conferences each year so parents can discuss their child’s progress one-on-one with their teachers.

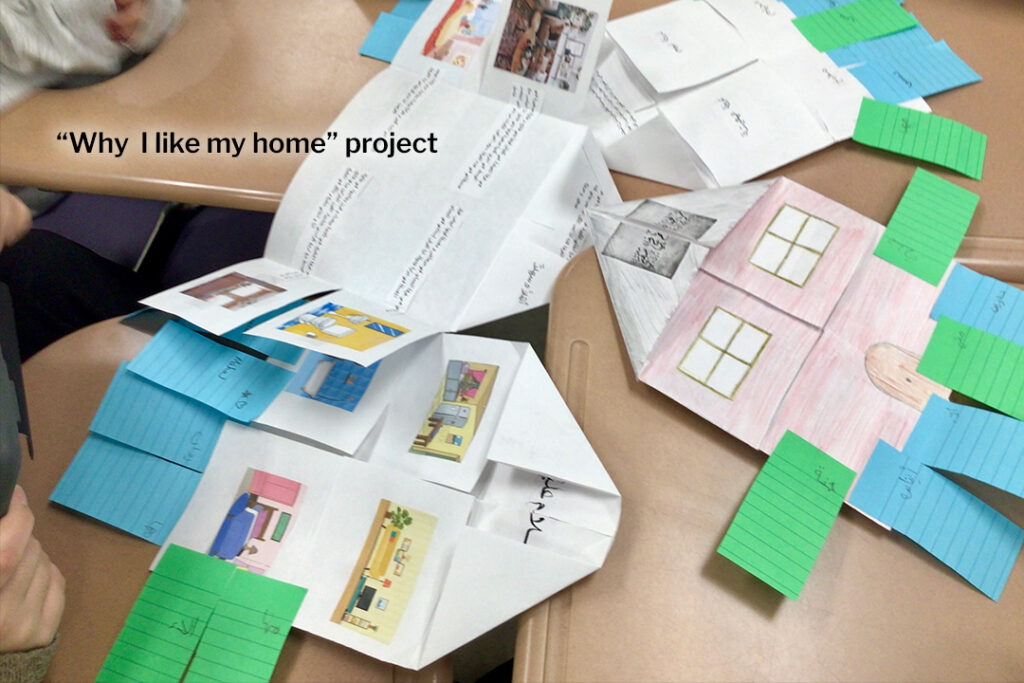

For families who speak Arabic or Spanish, we organize a special event. Our students who are learning the language give tours, read stories to children, perform traditional dances, bring dishes from Spanish and Arabic-speaking countries, sing songs, and hold a fashion show of the many traditional clothes of the Arabic and Spanish-speaking countries. This event is always fun and attracts many families as it is entirely in Arabic and Spanish. It helps bilingual families feel welcome in our school, and it’s good for our students, as they’re not only practicing the language they are learning but also helping others.

When you come to a new country, there’s culture shock. You don’t have friends, and you have a new language, new culture, new education system. Everything you know, you suddenly don’t. It’s so difficult if you are in high school because that is the age when you want to become independent. Everything you have learned so far would have prepared you to become independent, but you are in a new country and what you’ve learned will not help you. So you’re kind of a baby now, at a time when you don’t want to depend on anyone. For that, we need to be patient with newcomer students.

I was teaching English language learners in bilingual Arabic classes. There were many cultural misunderstandings. Many students were going to the dean’s office, and there were clashes and fights. The students had very low self-esteem, and I was their third bilingual Arabic teacher in three years. Students felt like nobody wanted them.

I had never been to an American school, so everything was different for me too. Little by little, we started to develop this relationship. And by the end of the first semester, their behaviors started to change. During the last week of the semester, they asked me, ‘Are you going to be here next semester?’ I said, ‘Yes, I’m not going anywhere. I will be here until you graduate.’

And this provided the stability that they needed.

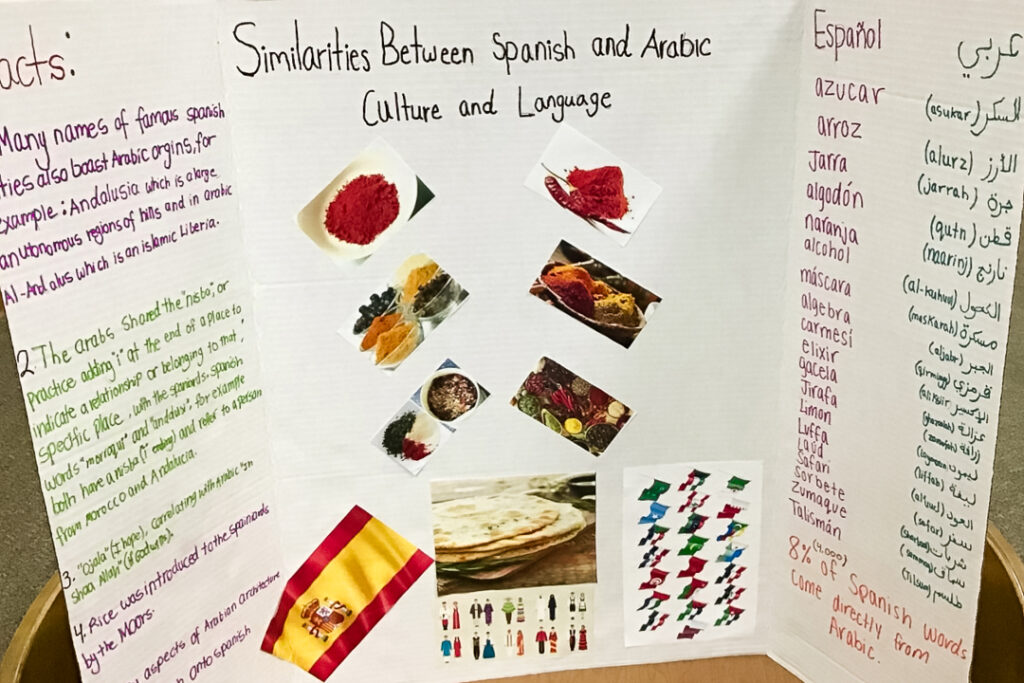

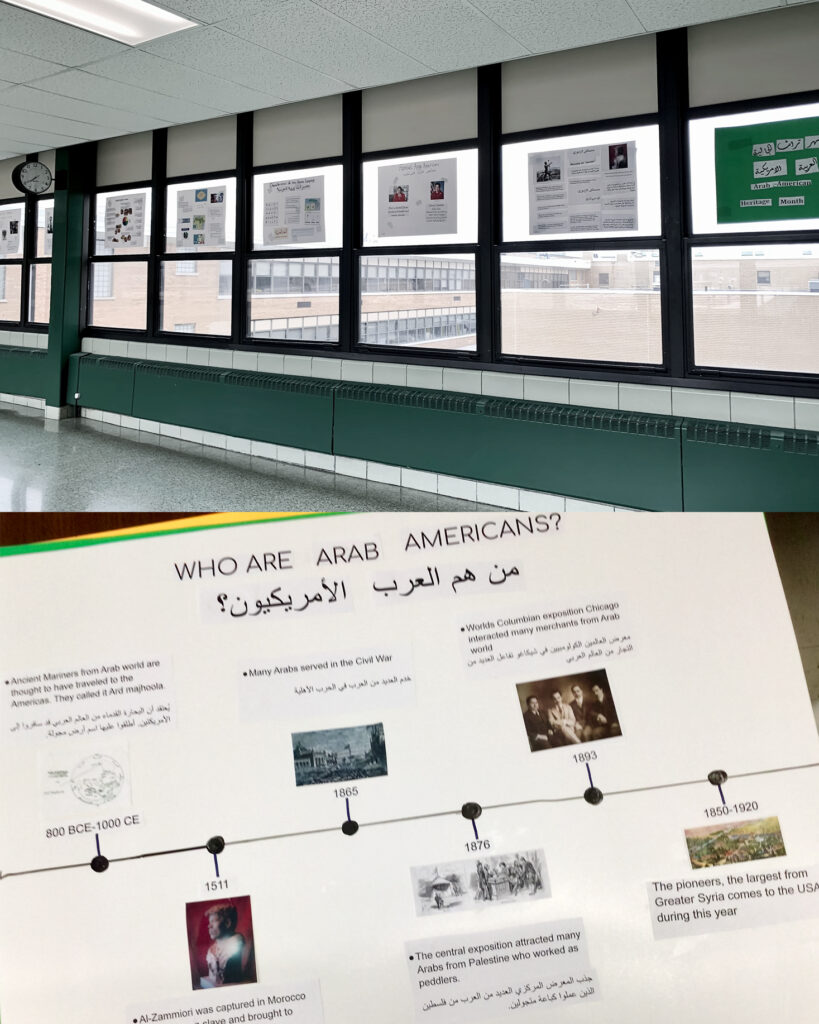

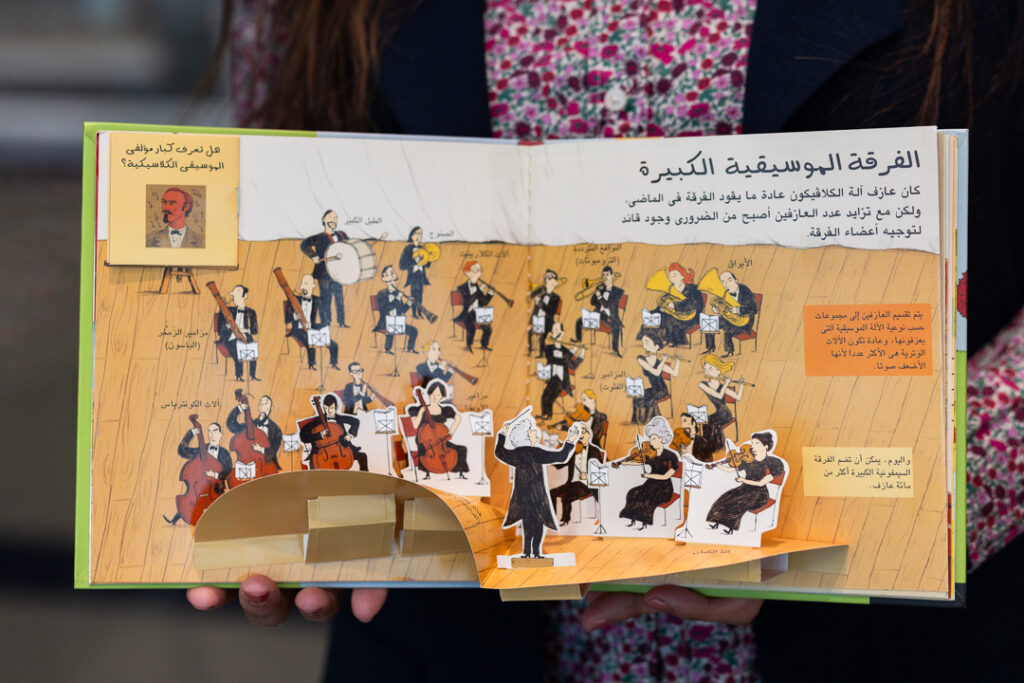

Everything is changing for these students. They need the confirmation that nothing is wrong with them. That’s why I proposed to offer Arabic as a world language at our school, along with Spanish and French. It confirms their identity and teaches others about the cultures and traditions of students’ original country. Now my students have a class where they are the experts.

In high school, we teach five or six periods a day, and then we do grading and planning. It’s a lot. Many countries allow closer to 40% planning time for teachers, and we’re not even close to this.

For example, my schedule has two planning periods and 20 minutes for lunch. The rest of the periods are leading classes, and you cannot leave your classroom. It can be so stressful. If something happens between this period and that period, you must still carry on because there is no time to decompress, unless you request a substitute to take over your class, which you don’t want to do so students won’t miss instruction time. This exposes teachers to ongoing secondhand trauma without the ability to unpack their emotions and sometimes even without realizing the harm this exposure is doing to them.

The teaching load needs to be lowered, but how can we lower it with an ongoing teacher shortage? It’s a cycle, because the load is one of the reasons why teachers leave. If we could lighten the load, teachers would be more likely to stay.

There are several ways districts are working on this. For example, block scheduling to allow both teachers and students to focus on fewer subjects a day and to provide longer passing time between periods for everyone to decompress. Another example is common planning time, which my district does, to allow us to collaborate, share resources, and mentor new teachers.

Another new idea (that’s easy to implement with no cost) is flexible four-day scheduling where students go to school five days a week as usual but each teacher only teaches four days, with the fifth day dedicated to planning remotely or in person. This means each class meets four days a week on a rotation. For example, if you have 100 teachers, each day only 80 teachers lead classes while the other 20 (who could be of the same subject or grade level) spend their time grading, planning, and collaborating. This flexibility would give each teacher an additional day per week for planning, which will improve teachers’ mental health and reduce burnout.

To help retain teachers, we need to address racism and harassment in schools. As a teacher of color, throughout my career, I’ve experienced microaggression, racial slurs, and offensive comments from staff and students. A coworker told me, ‘You don’t know how to speak English.’ A group of students called me a racial slur. If this was my experience, and I am a staff member, what is our students’ experience like? We need to create policies that reduce racial harassment in our schools to create a safer and more welcoming environment for all.

During my policy fellowship with Teach Plus Illinois, a group of us worked on developing and passing the Racism Free Schools Act. It was signed into law and will be implemented this coming school year. RFSA mandates schools to create a specific policy addressing racial harassment and share it with staff, families, and students. It requires districts to provide training for staff on recognizing and reporting racial harassment. Currently, Teach Plus, ISBE, IDHR, and UIUC are collaborating to create a model training that will be available for all districts at no cost.

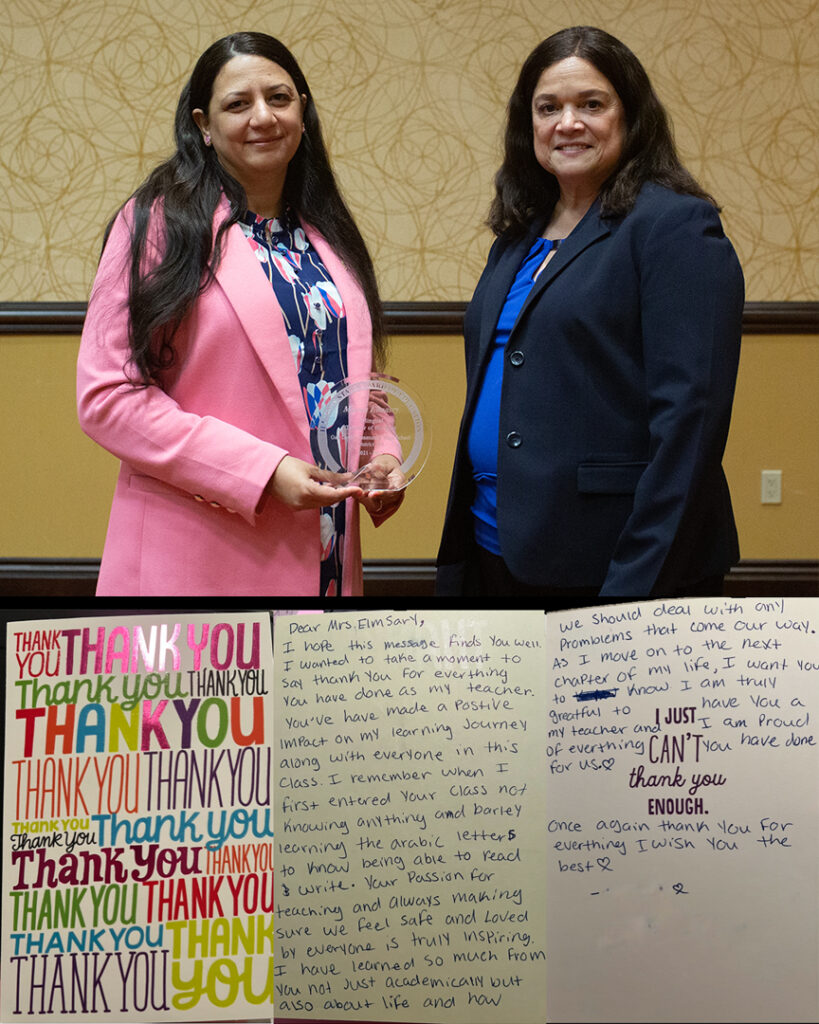

I think teachers will stay if they feel appreciated. Districts can follow District 229’s example in recognizing minority teachers: teachers of color, one-teacher departments like music and art teachers, those who work with historically disadvantaged students, ESL and bilingual teachers, and special education teachers — especially those who teach students with low-incidence disabilities. We need to recognize those teachers. If you teach students with interrupted schooling or who are in the process of learning English, you need to put all your teaching skills to use to help them; it’s different from teaching a class where students might be able to handle the material by themselves.

We need to appreciate those teachers because they provide stability for students and connect with them. Students see themselves in those teachers. I didn’t realize it until I saw how happy my students were when I received the Illinois Bilingual Teacher of the Year award. I heard them talking about it with pride. Seeing a teacher who looked like them being honored made them feel appreciated too. It gave them hope that they’d survive and become successful too.

Nothing beats a simple note from a student, watching a colleague being honored, or seeing a student (especially one who was struggling) become happy and successful in all aspects of their life.

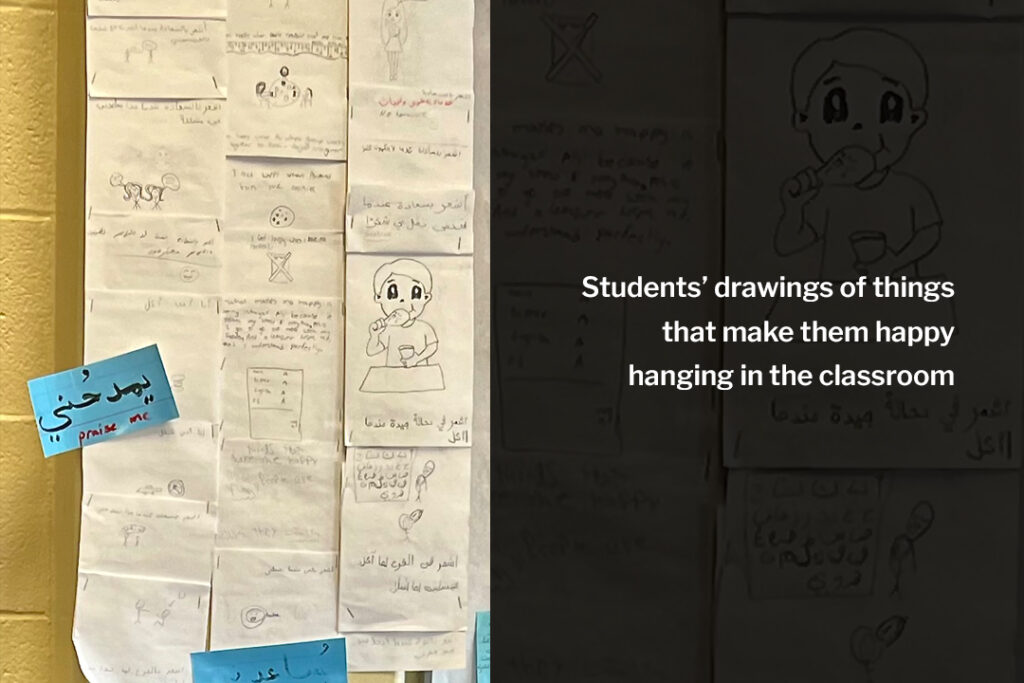

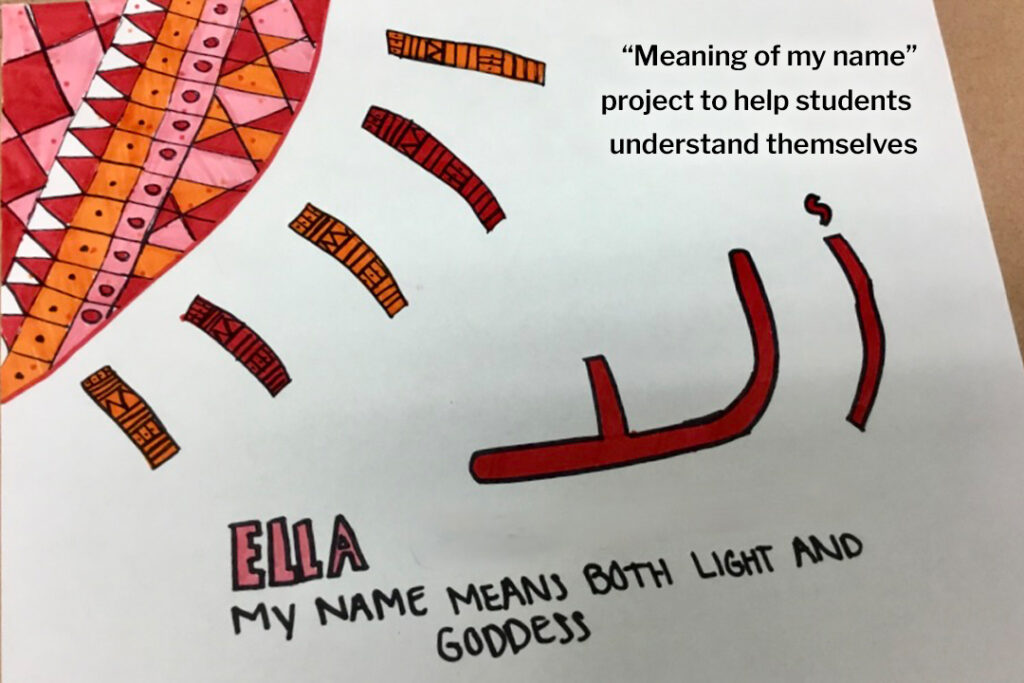

Each year, I ask students to draw two things that bother them the most. To build a community in the classroom, we have to interact with each other constructively. I tell them, ‘How will I know what is bothering you unless you tell me?’ I ask them about things that make them happy too so that I can do them more. I love my students and I want them to feel relaxed in my classroom. I don’t want to do something that hurts their feelings, and I want them to be sensitive to their classmates’ feelings. This drawing activity helps them recognize their feelings, show empathy to others, discuss difficult topics like racism, and connect as a class realizing our similarities.

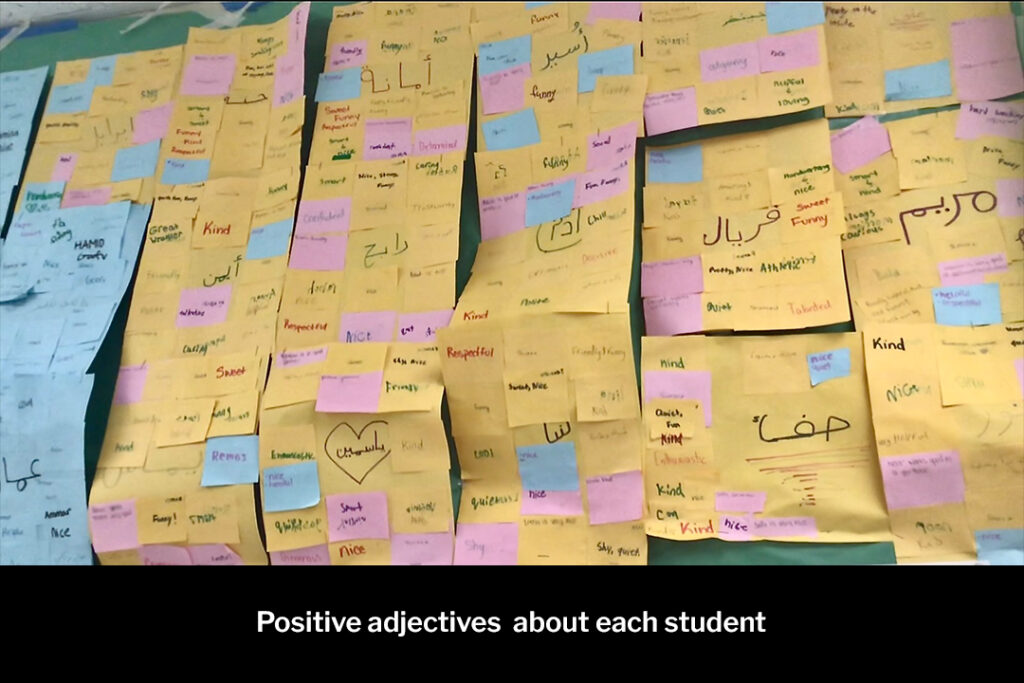

I ask students to write their names on a paper and pass around Post-it notes. I say a student’s name, and everyone must write one positive adjective about that student. I collect and review the notes, add mine, and hand them to that student. After calling the names of all the students, the class glues the Post-it notes onto their papers and we hang them in the class. This activity helps students see good in everyone, including themselves, and discover traits that they might not even know about themselves. I see my students bringing their friends to my classroom to show them their papers!

Our students experience many challenges, uncertainties, and even trauma. In order for our students to learn, our classrooms need to be the oasis in their lives, or waaha in Arabic, where they can safely put their guards down and let their authentic selves shine through. Those activities help create this waaha.

Many community colleges and universities offer Arabic, so schools should not be afraid to offer Arabic too. Only four or five districts in Illinois offer Arabic despite the large interest. There are challenges like finding qualified teachers or allocating funds. My district used the Arts and Foreign Language Education Grant to help start our Arabic program.

The biggest challenges are the myths, stereotypes, and even prejudice about the Arabic language and its peoples, so I think we should just address those out in the open. One of the myths is that Arabic is too hard to learn. But because Arabic is phonetic, the words are pronounced the way they are written with no silent letters, making it easy to read and write.

America is diverse like a beautiful garden with different flowers. Each has its own beauty. We need to stop othering people who are different from us and start learning about the beautiful cultures of those who live among us, like Arab Americans. We need to enjoy our beautiful garden, our country.

–Marwa Elmasry

World Languages/Arabic Teacher at Oak Lawn Community High School

2022 Illinois Bilingual Teacher of the Year

2022-23 Teach Plus Policy Fellow

Oak Lawn, IL