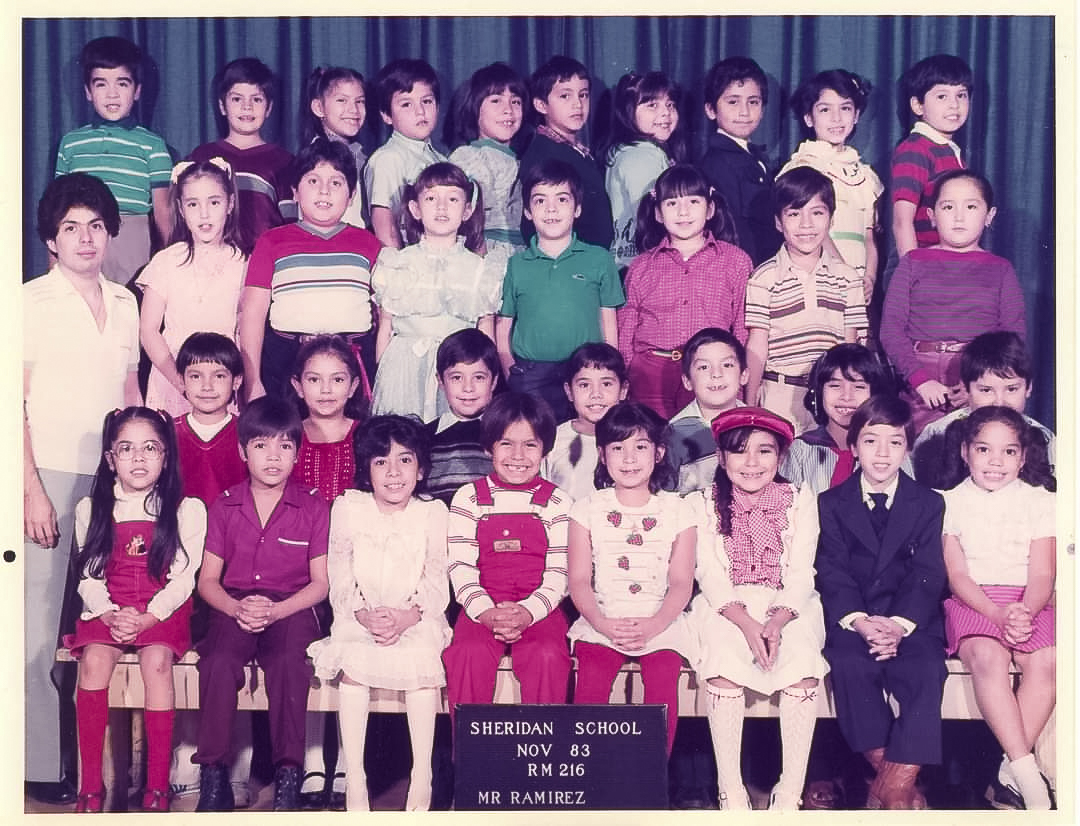

It’s hard to view my career in stories. Maybe it’s not even my story. Maybe it’s the story of my dad.

I grew up in South Chicago. My dad was a preschool teacher. And everywhere we went, it was like, ‘El maestro, el maestro!’ And so that made me a celebrity by extension: la hija del maestro.

He taught preschool, but he also taught ESL at the community college, and he took the kids swimming at the Y on Fridays. He did tutoring at the high school, and the school was definitely the center of the community. I remember when I was little, one of my dad’s families had a house fire. And my dad was the one who was fundraising. My dad helped students and families survive the hardship.

My dad did not want me to become a teacher. I went to University of Chicago, and he told me, ‘You’re not gonna go to a school with this tuition and then make a teacher’s pay.’ He was concerned about the income, but he was also concerned about the unbelievable amount of time and energy he knew teaching took. He was concerned that when I had children, teaching would draw me away from them.

So after college, I worked for a while at City Colleges of Chicago and then at a small nonprofit where I wrote grants and helped with youth programming. I worked with kids through Upward Bound.

But then my husband got sick.

He was getting his master’s degree during his illness, and we always said that after he was done, I was going to go back for my master’s degree. My master’s was always part of our plan, but not necessarily for teaching.

It was a three-year battle with cancer. And then my husband passed away.

I don’t know that grief ever ends. But you have to get used to a new tomorrow, a new normal. And it made me think about where I was happiest: as a student in the classroom, and working with students in youth programming.

I wanted to start a new life.

I wanted a sense of direction for myself and my two kids.

So I went through a transition-to-teach program. And it was the best decision I could have made.

I love my job. Are there aspects that I would change? Of course. But in general, I get to come and hang out with youth every day and talk about books. This is the dream.

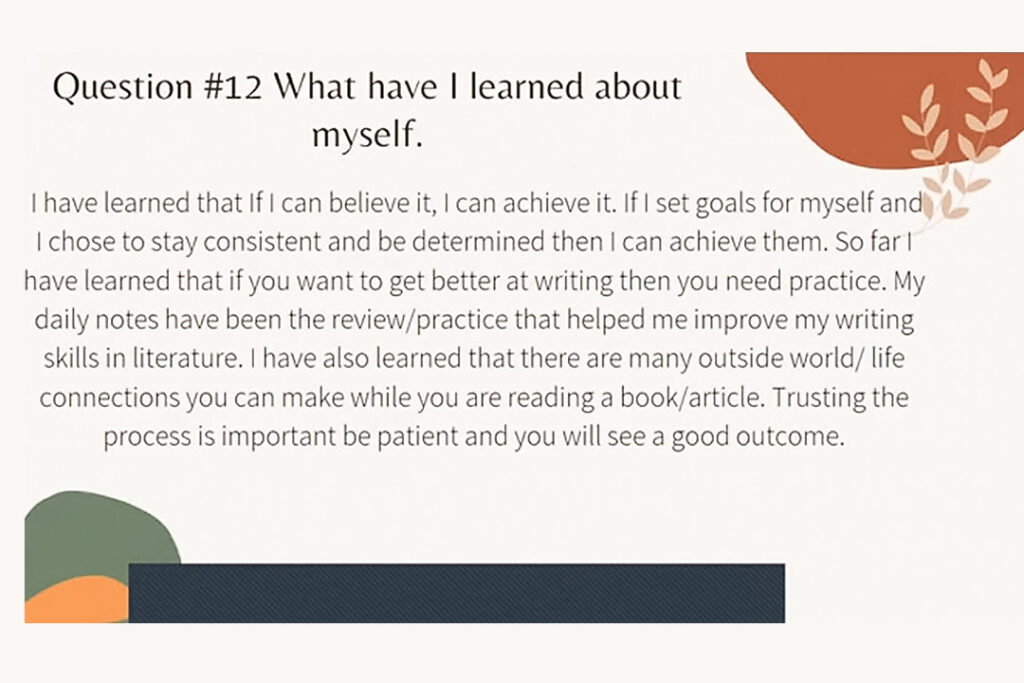

I think studying literature changes the way you walk through the world. And to be a part of that in any way is overwhelming. I have a portal into tomorrow, looking at these children.

What’s beautiful about high school is that they come in with their experiences and their opinions, but they’re not hard set. They are always changing their minds and asking questions. So that’s the coolest thing, being a part of it and seeing the fireworks — watching someone who’s struggled to have that ‘aha’ moment finally have it.

I always use the example of the Derek Chauvin trial. There was a woman who worked at the Speedway who took the video of George Floyd, and she knew in her own mind why she was taking the video — it was very important to her to take that video and to turn it in. But when she was on the stand, she did not have the command of language to explain what she saw and why she thought it was important. That had to be frustrating for her, to recognize the importance of that moment and not be able to deliver what she wanted.

And God forbid that that’s ever any of my kids, if they need to use their words to defend themselves or someone they love. I want them to have the tools to advocate for themselves, and so much of that is language. Being a part of them developing that is amazing.

It takes two seconds to fall in love with these kids, and it’s amazing how very little it takes for them to love you back. It fills you up.

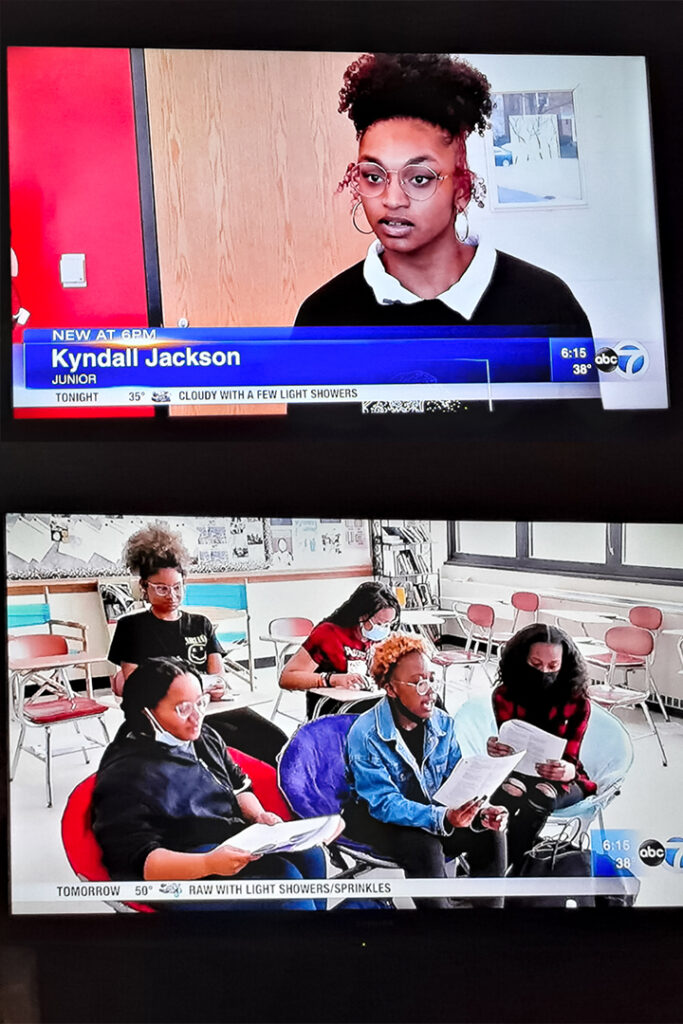

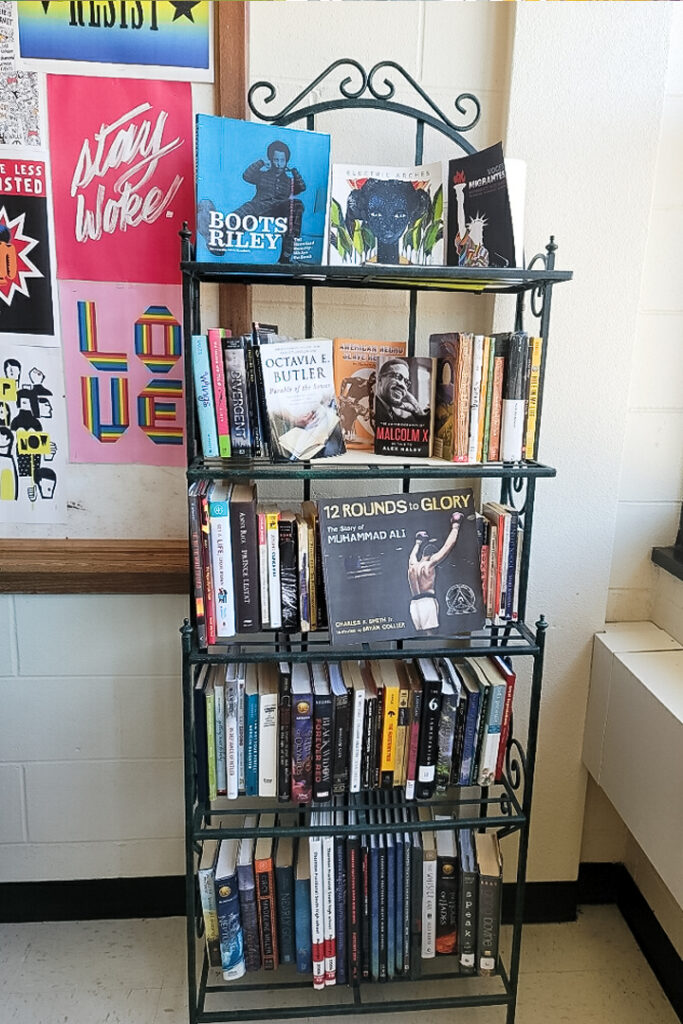

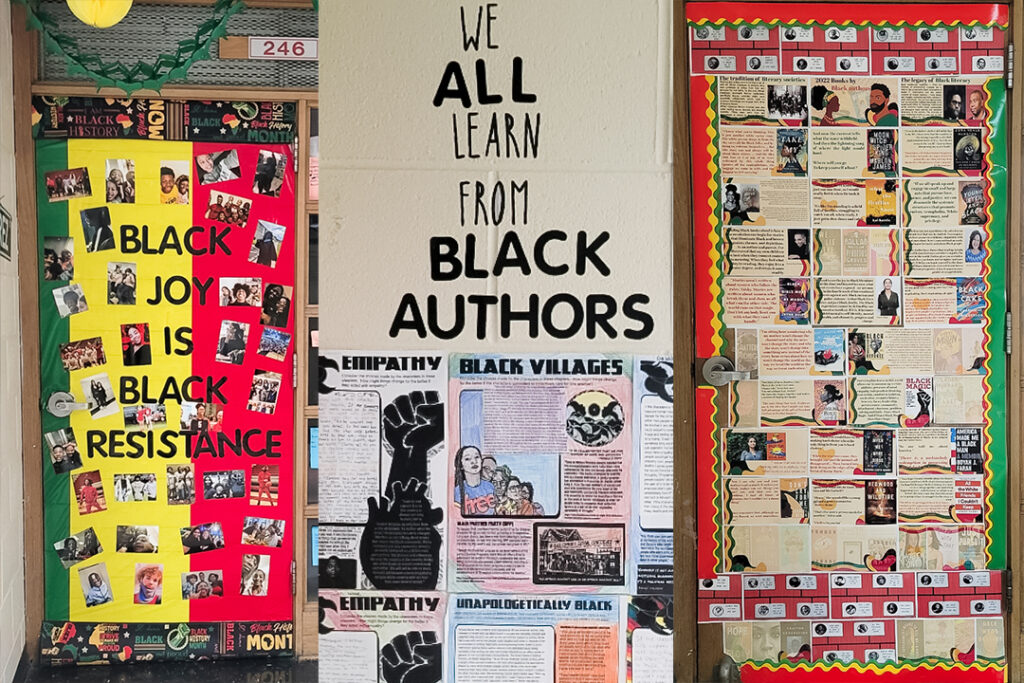

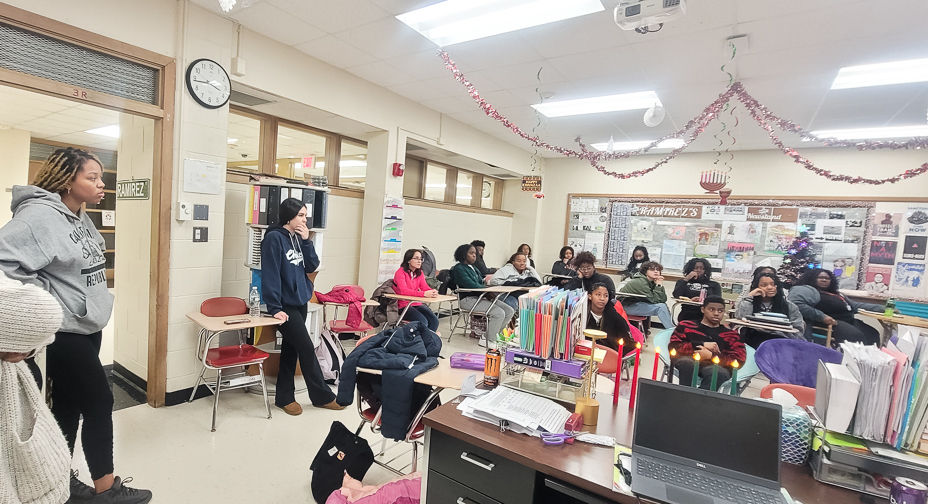

I teach four sections of English 9 and then yearbook. We start the year with Shadowshaper, which is a book about an Afro Latina teen. It aligns to the hero’s journey, and we pair it with The Odyssey. It covers racism, sexism, gentrification, and the power of heritage.

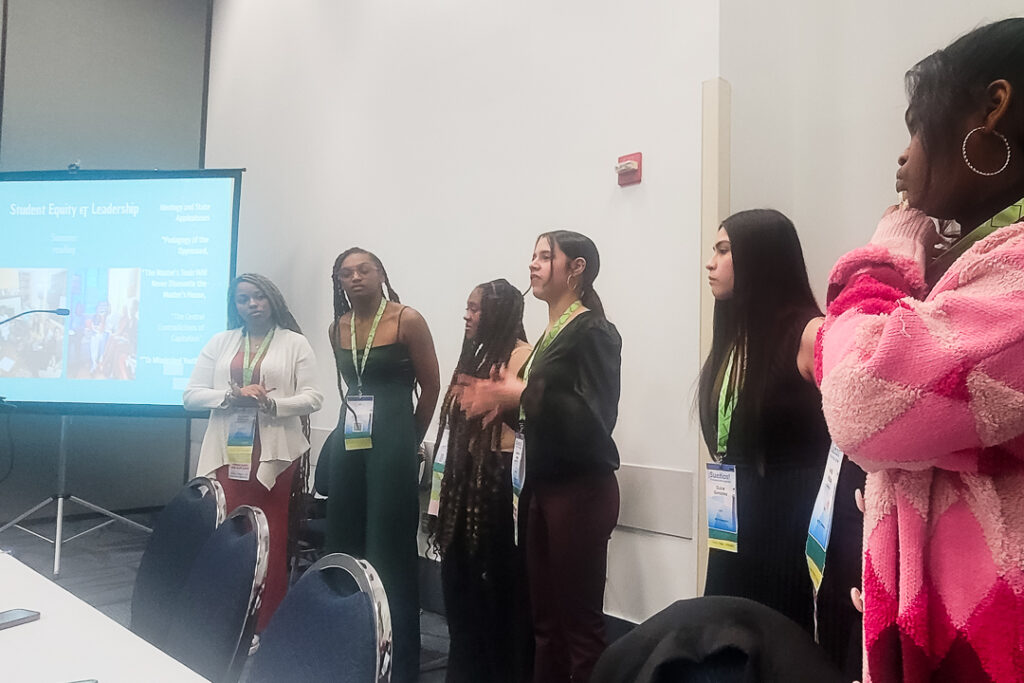

We also read Maus and Maus II, and then Parable of the Sower. We’re trying to get more representation, so students can talk about things that are relevant to their lives. A bunch of my kids just went to the National Council of Teachers of English conference to present on how curriculum influences student activism. And it’s been beautiful watching how they can take fiction and turn that into lessons for their own lives.

I’m the sponsor of Student Equity and Leadership, which is a newer club. We had something called Student Support Wednesday, where the students could meet with teachers in areas where they were struggling. The school board was going to take it back, and the students organized and got a petition out that they presented to the board. The board didn’t take away Student Support Wednesday after that, and it was great to watch how the students took a stand about something that was important to them.

This year, they’ve raised questions about the over-policing of students in the school. There are some changes that have happened of late that they’re working to combat – like that loud siren you asked me about, at the end of the school day. It’s unnecessarily aggressive, to encourage students to make their way home.

It’s definitely interesting watching the kids as they begin to think about issues of race, class, gender, and power. They’re starting to grow into advocates for themselves.

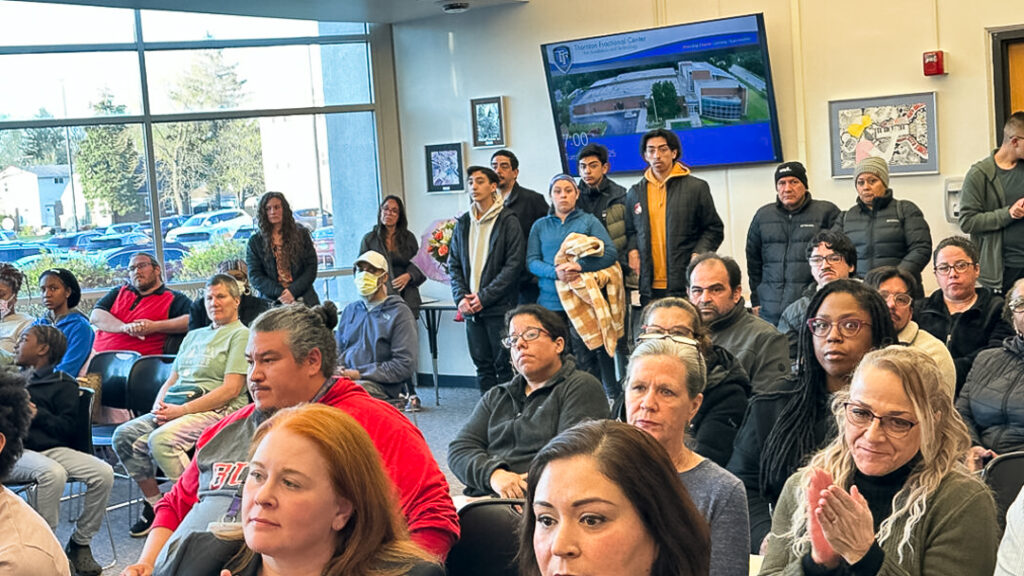

Recently, nine of my students went to address the school board about different issues and concerns. I was so proud of their poise and the preparation they put into composing their statements — their courage. At their age, there is no way I could have done that.

Education is so much more than standards, and I remember that when I see how this work develops their character and their confidence.

I think all teachers have moments when we consider leaving. I can’t say that I’ve had a serious one. But I do know that when things are tense in the building, that definitely makes a difference. When there are changes and they’re unexplained, that makes a difference.

It’s difficult for me to walk into my classroom because it used to be beautiful. I had area rugs, bookshelves, bungees, and that was okay for four years. And then all of a sudden, there was a snap decision: no outside furniture. I felt demoralized, explaining the bare room to my students when they walked into their learning space.

It can be emotionally exhausting. When I’m with my own children, I feel guilty that I’m not doing work. When I am with my students, I feel guilty that I’m not with my children. It could help if there were less paperwork — fewer binders full of documentation and evidence and evaluations. If it’s not necessary, cut it. But it’s tough to determine which pieces of teacher accountability to cut while simultaneously battling deprofessionalization of teaching.

Where I feel extraordinarily lucky is that in both of the schools where I’ve worked, my principal has been incredibly supportive. And that makes a huge difference. Feeling respected and trusted has made a huge difference here. I feel like my administration has my back and that they trust that I’m doing the best for my kids.

This is a Title I school. We are about 60% Black students and about 20% Latino students, and the deficiency narrative about the kids kills me. They are the smartest, most creative kids, and people make judgments based on things as superficial as durags.

If people could conceive the magic that happens in these babies’ brains, they would invest in public education more. The cure for cancer has been sitting in one of these classrooms for decades. But because we don’t have the resources to fully educate our children, the world gets hurt.

We are all missing out on the potential that is here every day, that is so clear to see if people would be willing to see it.

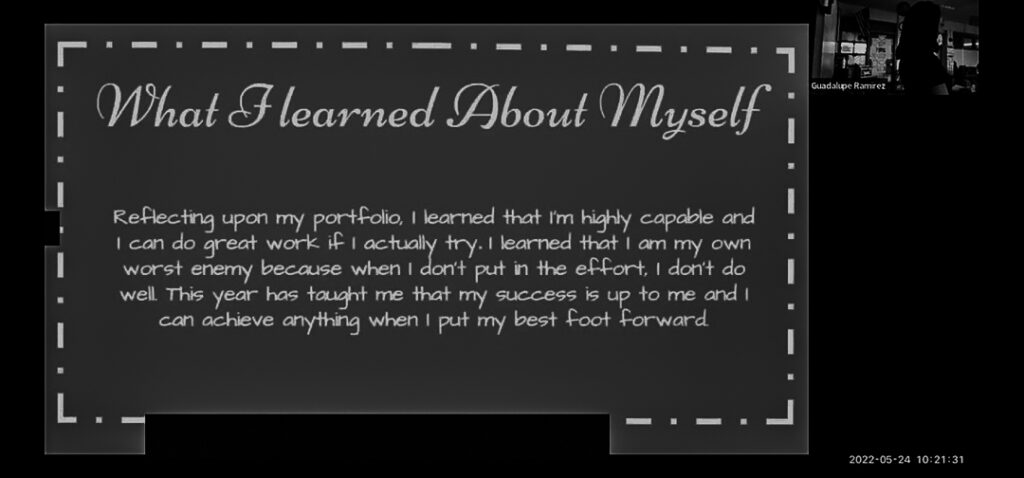

My students submitted their National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) proposal on a longshot, because it’s typically only teachers and professors who present. I told the kids that they shouldn’t expect their proposal to be accepted — but it was. So then we had to get to work.

The high schoolers came to my house every week over the summer to prepare, for no less than five hours each week. They were so serious about it. And that wasn’t the only time. We have a future teachers program here, and over the summer, my students prepped readings and taught at the program. It was a unit on student voice, so I felt like it should be led by students. Each class period was 2.5 hours over two days, so they prepared five hours of material.

There’s this narrative that students are lazy. But they did this for no grade. They are starving for brain candy. They pushed me, because I was not expecting to dedicate as much of my summer to this as we did. But how can you say no, when kids ask to learn?

The other thing that’s unbelievable is the love you get from parents. When the proposal was accepted, we had a barbecue to celebrate. The parents said ‘whatever you need,’ and they came through with that, times 100.

Being a teacher is such a weird life. It’s so strange, because all of a sudden, people who would be strangers are like your family. Like my birthday, over the summer. The kids dropped by and left flowers and cake on my back porch. I don’t even know how they knew it was my birthday. It’s overwhelming, the richness it brings to your life — nonstop.

There was my life before teaching, and there’s my life after. Now that I’m teaching, my life is completely transformed.

The high school teacher prep program is part of our district’s initiative to recruit and retain more teachers of color, because that’s been a struggle. There are so many obstacles, in general, to becoming a teacher. I waited tables while I was going through my teacher prep program, and the program told me I had to quit, because I wouldn’t have time to do both. But I was paying tuition, and there’s no way I could afford to quit. There are obstacles beyond interest in teaching. But I do think a program for high schoolers like this is a great way to create interest.

I also think it’s important to dispel the doom and gloom about teaching. When I tell my kids, ‘You should become a teacher,’ they say, ‘Oh my God, why would I ever be a teacher?’

I tell them, ‘Don’t you see me come in with a smile every day?’ And depending on the district, the pay isn’t always awful. There are districts that are competitive. And it’s so rewarding.

So positive stories about teaching are important. But positive stories about learning are important, too. If kids hate school, why in the world would they ever want to become teachers? We need more honey than vinegar. If we show them a joyful classroom, it’s easier for them to imagine creating that joy for other youth.

March (two months later)

I resigned a few weeks ago, effective at the end of the school year. Students were exercising their voice, and I was called in for discipline. The administration felt that our Student Equity and Leadership club was encouraging kids to speak out too much, and they dismantled and suspended the club.

Resigning was really, really difficult for me to do, because I love the kids here, and the families are amazing. As much as this has been a difficult year, it will probably be a highlight of my career overall: having the students’ proposal accepted to the NCTE… and one of my students got accepted to University of Chicago. Her essay was about me. It’s been beautiful. It’s been difficult, but I wouldn’t give up this experience for the world.

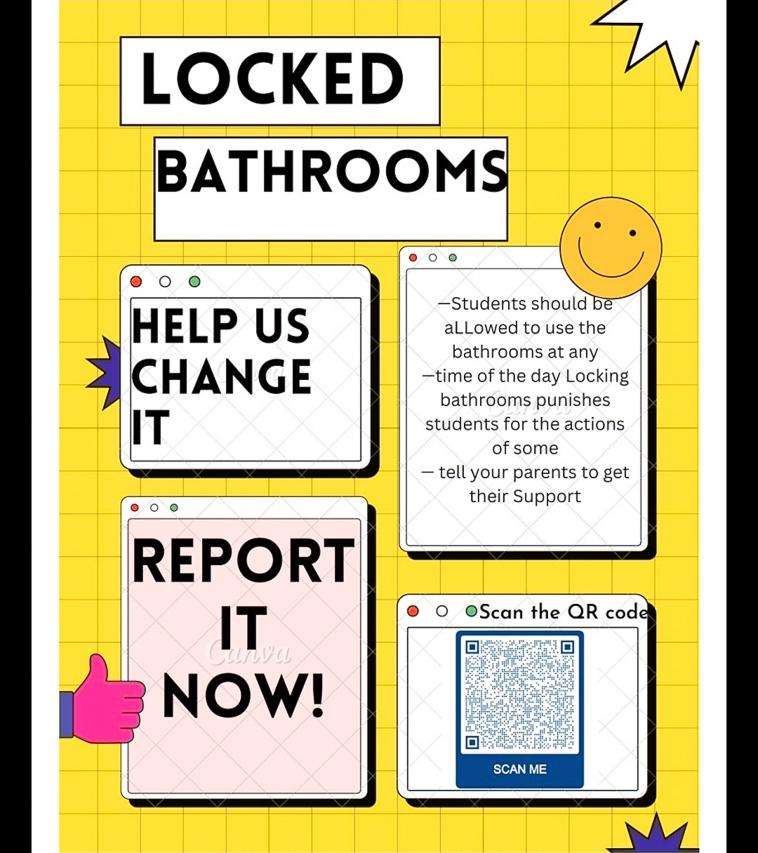

Certain things that the students were requesting, in my opinion, were very reasonable: please stop locking the bathrooms, don’t bring K9s in for searches. Increase the academic rigor, include students on curriculum teams, don’t put deadnames on student IDs. I was expecting that they would be welcomed as collaborators to change some of these things. But that was, unfortunately, not the case.

This has been a great lesson for myself and for the students. A lesson about power. With the club dismantled, they were discouraged from speaking at board meetings. So for the last few, they were silent. They went to the board meeting, but they didn’t say anything. And then they decided that they don’t need the club to express themselves. They have something to say, club or no club. They asked their parents to speak with them. And that’s powerful, when you have a child go up to speak and their parent stands with their hand on their shoulder.

It’s a great lesson of the gains you can and cannot win. They may have the power to dismantle the club or discipline the teachers, but they don’t have the power to break down the community that you make with parents and students. I hope the students take that lesson away: you don’t need the institution to exercise your power.

If you’re not in the classroom, you might think that what’s good for the students is compliance — obedience and good behavior. But I think that what the kids are coming up against goes against the very purpose of public schools. They were asking for more teachers of color, more diversity in the texts. They have questions. Some of the stuff we do, while perhaps very well-intentioned, does harm.

Like with the K9 searches: there have been weapons found in the school, and sometimes our kids smoke weed in the bathrooms. These are real concerns. However, that’s not the bulk of our students. And when the K9s were brought in, the students said, ‘This makes me feel like a criminal.’ Self-critically, when the K9s came in, I didn’t think anything of it. I told the kids at the top of the hour, ‘If you need to use the bathroom, use the bathroom now, because once the bell rings, I’m not gonna be able to let you out.’ I really, really didn’t think anything of it. But the students felt criminalized.

Part of our job is to keep children safe. That becomes tricky when you hear the pain in their voices. How can we do it differently? Or how can we do it better? These children are dying to get involved. They might come up with something — they are so creative. But we’re very stuck in ‘this is how it’s always been done, and so this is how we’re going to do it.’

And if you’re an adult whose style of teaching is based in obedience and authority, then when that’s threatened, it can set you off.

Lansing is interesting in that the demographics changed quickly. There was an NPR story about it called When Students Are Black And Teachers Are White. About 20 years ago, the school was probably 70% white. And now the school is less than 10% white, with 90% minority enrollment. However, the neighborhood is still very white.

When we retired the name ‘Rebels’ (as in Confederate Rebels), social media was ablaze with racist comments. There are voters who are active and vocal, and the students can’t vote. So I do think that to some degree, if board members are trying to stay on the board, they may feel beholden to take certain perspectives into greater account. There are people with deep roots here in Lansing.

I am loyal to South Chicago, so I understand loyalty to an area. For the community here, they were attached to Richie the Rebel. Their band uniforms were Confederate uniforms, and those got taken away. And then we started taking down the Confederate iconography in the school, and in 2020, we lost the name Rebels. That was part of the community’s identity, and now it’s gone. Being from Lansing meant this very particular thing to them, and if it’s not that way anymore, then who are they?

For someone who grew up here, maybe their identity is so deeply intertwined with the history of Lansing and what Lansing ought to be, that any change threatens something identity-wise for them. And I think that is why they resist it so fiercely.

There are wonderful people in Lansing. But there is a small contingent of vocal people who are afraid of losing their sense of self. Maybe they’re afraid of not being able to see the high school where they grew up anymore. So it’s harder to see the beauty.

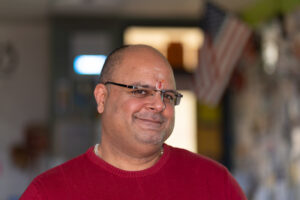

My principal sent me a picture from a parent who’s a graduate of TF South, and this graduate was so excited when he saw the big sign outside my classroom that says ‘Ramirez.’ He said, ‘When I came to school here, there weren’t any other Latino students.’ Seeing a Latina teacher brought him joy.

But with his joy and pride comes fear, because for the people who used to call this school home, they don’t know where their deep joy and pride has gone.

April

Teachers are worried about what we can or cannot teach. Academic freedom is on the line. I think that stems in part from a lack of understanding of the history of public education.

The architects of public education were intentionally nation-building. They understood exactly what they were doing in creating this educational experience. They understood that teachers’ roles in education have never been neutral. And I think today’s teachers need to be aware of and take seriously our role in nation-building. Are we going to maintain the status quo, where there are larger and larger divisions between people? Or are we going to work to subvert that?

In Illinois, there are culturally relevant teaching standards that require us to advocate for our students. There are standards that require us to teach difficult topics in the face of resistance. As teachers, we need to be brave, and we need to remember that what we choose to teach or not teach is going to impact generations.

Teaching is an act of courage. We need to be confident that we are experts not only in our content area, but also in our pedagogy. We are not only tasked with content, we are tasked with creating engaged citizens.

Right now is the time to elevate public education. We are at a critical juncture. In this moment when there is so much division and so much inequity, the next generation is going to make this world a better place — or not. When teachers are trying to bring up multiple perspectives, we are trying to elevate everybody’s humanity. Education can either lead to conformity or the practice of freedom, and we should continue to choose freedom.

There’s that saying by Paulo Freire: ‘Reading the world always precedes reading the word, and reading the word implies continually reading the world.’ Teachers work hard to help students do that. We are preparing children for a world that doesn’t exist yet. And so we have to teach them critical inquiry, even if it’s uncomfortable. Because the world depends on it.

Somewhere along the line, freedom and liberty and what that means got twisted. We shouldn’t be teaching compliance. We should be telling them that liberty means being revolutionary — dreaming of that different and better world.

The accusation of indoctrination is interesting because there’s no such thing as a neutral education. We are always choosing whose stories to tell. Textbooks and teachers curate the knowledge that’s most worthy. And in this moment of history, it is so important that students are able to understand perspectives that are different from their own.

Thomas Jefferson was a brilliant author and key in what this nation became, but he was also a slave owner. We’re not writing him out of our textbooks, we’re asking students how those two things sit together. How do we make sense of the good with the bad? It’s difficult. We have to be their guides, and we should help students understand that their education isn’t neutral. We’ve always told a certain person’s story and pretended it was neutral, instead of deliberately choosing counter-stories and having students sit with those two things at the same time.

What I love about education in general is asking questions, searching for answers, and recognizing when we’re wrong. Then we get to go back and figure it out. I worry with this attack on knowledge that our students aren’t ever going to be able to see the full picture.

We are forced to choose what knowledge is of most worth, because we see our kids for 55 minutes, five days a week, and we cannot teach everything. But we can be critical in the way that we teach. If students aren’t taught to be critical consumers of the world, then they’re not going to be ready for higher education. If they don’t have the tools to understand complexity, then we’re setting them up for failure — and we’re putting ourselves as a people in a rut, instead of fueling imagination and telling our students that they are producers of knowledge.

If you went to private school or your children went to private school, you may think that discussions around public education have little to do with you. But our public schools are resourced according to neighborhood, and differences in schools are exacerbated based on how they’re resourced. My parents felt that our local public schools didn’t have the resources that were needed for a quality public school education. My dad was a public school teacher, but my sister and I went to private school. It’s not always so simple.

I think that what everybody can do is fight for systemic change. So much of school performance is hidden. There are schools that, for whatever reason, have a commendable rating when only 8% of their students are reaching proficiency. I cannot fault a parent for not sending their child to that school, because it’s not doing its job. I think knowing how your local school is doing is important, whether or not you have a child: put pressure on leadership, but also come up with solutions and ways to get involved.

If there are issues of security, safety, or disproportionate suspension, there are neighborhood solutions. University of Chicago released this brilliant report on how to decrease school violence, and it was about more counselors, not more metal detectors. Being at a board meeting and bringing up that research could help push people in the right direction. It’s a lot of work staying up on what’s good for schools, but I think that collectively, people can do it.

There are schools that have grandparents come in as dean’s assistants — because you’re not going to mess with someone’s grandma, right? There are schools that have a parent ombudsperson, because discipline is less when there’s a parent there to fight for you. And the way our society is organized, some parents don’t have the time or the resources to go to school and fight for their children.

Ask the teachers, ask the PTA: what are the problems? How can I bring my unique set of skills and talents to make a difference? If you do that, you can help make schools worthy of your child. There are children there now, and they deserve every bit as much. We can all make those differences.

I feel overwhelmingly lucky to be a teacher at this moment of history. I think that the children today are beautifully defiant. They’re not going to accept less than what they deserve. And they don’t lack the courage of that conviction.

Let’s come together and try to understand how we can move forward. Where there are beliefs that do harm, let’s work to dispel them. Where there are different perspectives that can help us arrive at something new, let’s encourage that. Listen to children.

I don’t always agree with everything they say. And I don’t have to. They can do it on their own. They are organizers, and they do this in their own beautiful way. They’ll challenge me, which is also beautiful. They’re not going to sit there and take notes and just take my word for it. And that is so exciting. Because I’m often wrong. And I love it.

This generation of kids, they’re going to change the world, and it’s not going to be easy. I know there’s going to be a lot of struggle around it. But they are strong.

I am, beyond words, grateful to be a teacher right now.

–Lupe Ramirez

English Language Arts Teacher

Lansing, Illinois

Share a link to this story

…or see Lupe’s posts on:

Wondering how you can support Lupe‘s students? You can find their Amazon wishlists here:

Aayla’s wishlist

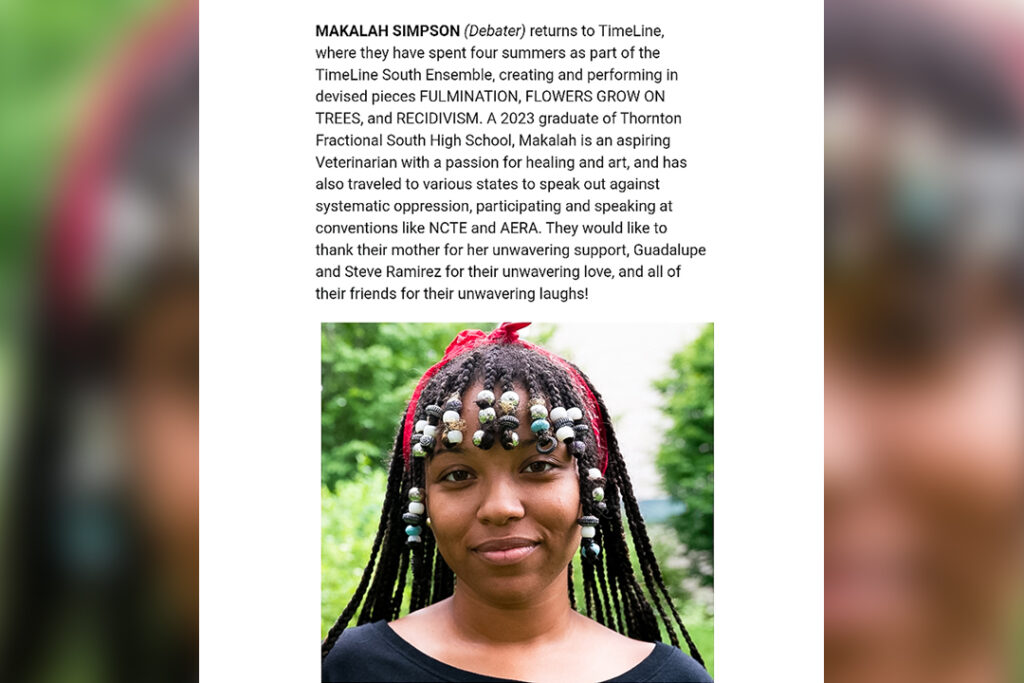

Makalah’s wishlist

College wishlist