I always thought I wanted to go into law. I saw all these courtroom drama TV shows growing up, and that’s what I wanted to do. I went to the University of Wisconsin–Madison with the intention of eventually going into environmental law, but I had a change of heart along the way. I really didn’t know what I was going to do, because I thought law was it for the longest time.

I worked with the Forest Service for a little bit, and then I traveled in South America for six months. I was massively in debt. I wasn’t sure what was next, but I just knew I didn’t want to go into law anymore.

I grew up in Minnesota, but I had a thing for California. When I came back from South America, I told my dad I was going to San Francisco, and he said, ‘You’re going to the most expensive place? You don’t have any money.’ He was right. I came out here anyway.

I waited tables. That’s the reason I’m still here — because I got a job waiting tables. I was looking for jobs in newspapers, because this was pre-Craigslist and all that, and I got a job selling environmentally friendly light bulbs. I was considering environmental consulting, and then I got a job temping in an office. I still waited tables at night. At the time I thought, ‘I’ll just work all these jobs and I’ll never get bored. I’ll always have some variety.’

Teaching high school wasn’t on my radar. I really liked college, but high school wasn’t my favorite chapter. The thought of spending more time in a high school wasn’t something that ever occurred to me at the time.

After working a handful of random jobs just to get some cash flow going in San Francisco, eventually I got a job with a company called Science Adventures, where all you needed was a degree in science. We’d go into these different elementary schools after school and lead science lessons, which was actually really fun. I mean, we had rockstar status at some of these elementary schools. The kids loved it.

I started doing sales for the company because we had to go in to get kids to sign up. I’d host this big science magic show. It was a great job, but I didn’t have a car, and I was going all over the place. I was using public transportation and sometimes even renting cars to go do these things. Once I took my expenses out of that, I wasn’t making much money. With all the other jobs I was juggling, I decided, ‘Something’s gotta go.’ Out of all those things, teaching the science lessons was the most enjoyable and the most fulfilling,

At the time, San Francisco had a teaching crisis, where they had a huge shortage of math and science teachers. I learned about the credentials, and it turned out that if you taught at this particular time, you could get emergency credentials. So I enrolled in a teaching internship program. This was 26 years ago.

I started out teaching summer school. Then I worked on the south side of San Francisco, in the Bayview–Hunters Point area, which was wonderful, but it was a challenging place to be. There was a lot of poverty and as well as occasional violence in the neighborhoods. Our school was full of young, super enthusiastic, inspiring teachers, but we collectively lacked experience. That happens a lot in the inner city. There was no curriculum, and no resources, but the kids were really fun and there was no denying their potential. We were a young group of teachers who all wanted to make change.

I would teach all day, and then I’d ride my bike to San Francisco State to do night classes. It was really intense. I was so strapped for cash. But at the same time, I loved the work. I thought, ‘Hell yeah, I will do this for $27 an hour.’

Soon enough, I realized how different of a high school experience I could create for students than the one I’d had. San Francisco is so diverse, especially compared to where I grew up in the suburbs of Minneapolis. I have fortunately been able to build a strong rapport with most students, which has made this whole endeavor all the more meaningful… Lots of positive interactions. It feels so different from what I experienced as a student myself.

When I first got hired, they were like, ‘You’re the science teacher.’ I asked, ‘Well, which kind of science?’ Turns out there was nothing in place. There were no standards. The students kept showing up for class and that created some creative pressure on me, especially in the beginning, I was coming up with ideas in my sleep. I started with a small bag of tricks, and then I built it up over the years. I love environmental science, but really all science.

I’m constantly learning, you know. That’s one of the paradoxes of this profession: you have this clear role as a teacher, but the learning actually goes both ways.

While I’m no longer in the mix in San Francisco, here at Menlo-Atherton High School, 20 miles south of the city, I still get a whole spectrum of kids and everybody’s bringing something different to the table. There are phenomenal students.

My school is located in an affluent area, but we have an incredible range across the socioeconomic spectrum. I’ve had kids who walked here by themselves from El Salvador. I teach multiple kids whose parents aren’t in this country, especially boys whose parents felt it was more dangerous for them to stay. These kids have all these different stories. So I’m learning Spanish, just constantly learning. That wouldn’t happen the same way if I were doing law. I also have students whose parents are venture capitalists and professors at Stanford. All different kinds of kids.

I think every teacher has hit the wall at some point, because it can be really all-consuming, exhausting work. The highs can be incredible. But when you feel like you’re not connecting, it can be a real grind.

Being a teacher makes me feel better about the future because there is hope in working with these kids. These kids are much more globally minded than when I was in high school. It’s a different time, but they’re compassionate. It’s really kind of heartwarming.

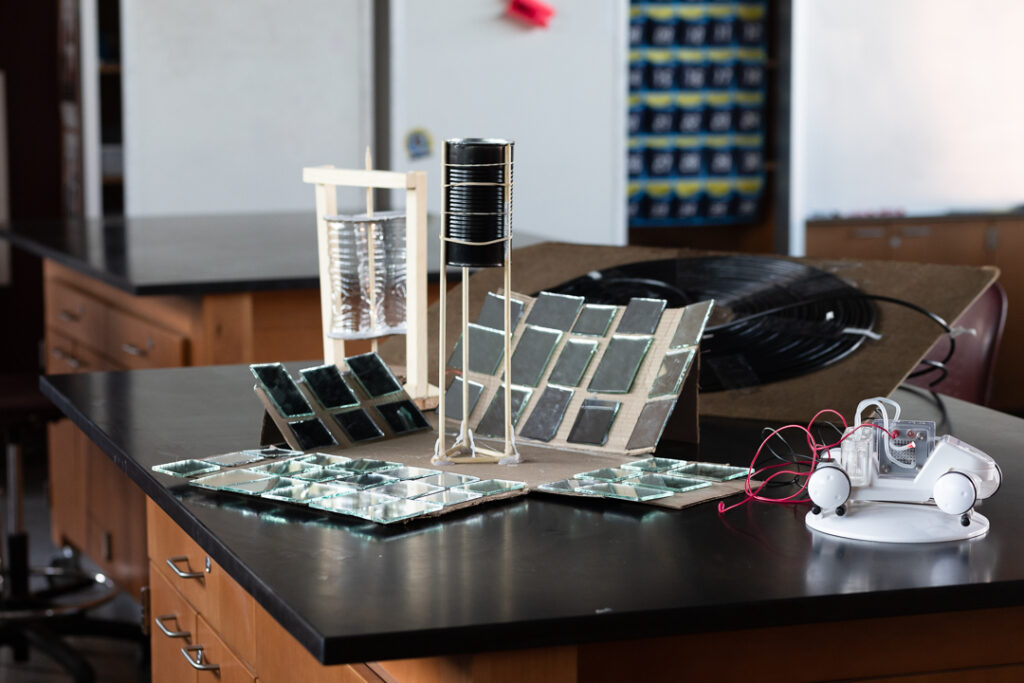

As a teacher, you play many roles. Sometimes you’re almost like a parent or therapist when the kids’ parents aren’t here. You’re doing all these jobs that you’ve got no training for, making it up as you go. Sometimes with the stage I set in my science lab, I have eight different groups doing eight different projects, and they all need different things. You are very much living in the moment as a teacher.

I want the students to feel like they’re empowered, to care about the environment, and to just like looking at the world. It all kind of comes together as we go through the semesters. We look at climate change, and then we make the link to food, fertilizer, and soil and how we do monocropping. We’re using all these chemical inputs that reduce the capacity of the soil to absorb carbon. The units all come together nicely.

This is our aquaponics system, which I call the mothership… it houses all the fish kids pull from to put into the systems their groups design. My goal is to always make what we learn as relevant as possible and solution oriented.

One of the fun things about Advanced Placement Environmental Science is a lot of kids come in already a little bit interested, and they’re so motivated and smart. We also want to make sure we’re pulling in and maintaining the diversity of who takes this course, so for some kids it’s way more work than they’ve ever done before. But once they’re out, some of the kids go on and do environmental science in college.

You see these kids, and while you’re with them it can seem like it’s a long time, but really you’re not with them very long. You’re one little spot on their life path. I have to constantly remind myself to keep that in perspective. It’s like, ‘Don’t lose the plot.’

I don’t know what the secret is to being a successful lifelong teacher. But I’ve worked at three different schools, and people are working so hard. That’s, I think, partially where the burnout comes from. It’s a labor of love. But at some point, you just get exhausted. And so all these little breaks that happen along the way, they’re so essential.

When I first started teaching full-time, I was broke. I taught summer school a couple of times, but I had to stop that in order to keep doing this for the long haul. I realized I needed to be able to recharge and do something different for a bit- change the mental channel for a bit. I don’t mind working in the summer, but I’ve got to get out of the classroom. I’ve got to be able to take a break.

I’ve been very fortunate in that I’ve had strong administrative teams, for the most part, because that is the dealbreaker for so many teachers.

This is my sixth year as the department chair. We’ve got 20 great people in the science department. I feel like we’ve done good work. But I almost think for the sake of any group, it’s good to rotate the leadership to bring in new ideas and mix it up a little bit. I took a role in the district for a little while. I try to keep it fresh.

I’ve considered going into edtech, since I’m here in Silicon Valley, where Google and Facebook are five minutes down the road. I don’t know if I could get the same satisfaction out of doing that work. But I think for teachers who aren’t supported or aren’t paid a living wage, moving into other careers can be very appealing.

You hear stories about teachers working jobs on the side. It’s really a sad state of where we are, as a society, if a full-time educator needs to work side jobs to pay their rent.

Most people in public high schools in California are teaching five classes, and that’s one too many. I think it’s one of the reasons for burnout. I mean, we’re teaching on an industrial level. I’m a department chair, so I don’t have quite the student load as most teachers.

There are plenty of teachers on this campus who have 150 students, which means 150 papers to read and grade. It’s brutal, because even if you could somehow only take 30 seconds to assess each paper, that’s 75 minutes for every assignment. You have to really pick and choose how you spend your time. You have to be intentional.

In a lot of districts, you have people who aren’t getting paid what they should be paid. You’ve got administrations that maybe aren’t as supportive, or they’ve got to answer to the superintendent or their test scores are low or whatever. It can all come down on the teacher, and I guess I don’t know what the answer is, but I know that teachers are working hard. If we could give every teacher one less class to teach, maybe we could give the kids more feedback. We could spend more time collaborating.

At my current school, we’ve got 200 people on staff, but I hardly ever see them. It’s a big campus (33 acres) and everybody’s so consumed with what they’re doing. How can we create a sense of community on campus? That’s one of the things that really hit me during the pandemic. It continues to be a challenge and probably one for any larger school.

It’s hard to create professional learning communities. How do you build those kinds of human connections in a school, where people want to be a part of it, they feel like they’re fulfilled, and they feel like they’re being recognized?

Every single day, each teacher makes thousands of decisions. So much work and so many interactions will never be recognized. I’ve certainly hit the wall along the way and thought, ‘I don’t know if I can keep doing this.’ And then there’s a break and I can come up for air, regroup, and soon enough I’m ready to jump back in with another group and usually with some fresh ideas. Teaching science keeps me coming back year after year.

I try to mix things up and teach new courses, and I try to keep my courses as hands-on as possible. For my AP class, I don’t do lectures — there’s as little of me talking in front of the room as possible.

I see science as the vehicle for teaching kids. It just so happens that I teach science instead of math or English or something else, but in general, I’m trying to teach and help these kids. Not that I have it all figured out. I’m modeling all the time and thinking, ‘Okay, this is what it looks like to be responsible. This is how what I’m doing will influence these kids.’

We have different projects. For example, we just did a unit on ethanol. We ask questions like, ‘Should we be using apples to make ethanol to put in our cars?’ We look at the reality of it. What is the energy future? And what’s disruptive? It’s all so relevant. I think that’s what makes Environmental Science especially fun to teach, because the relevancy piece is never lost. It’s always right there, you know. Your entire day, every decision you make has got some kind of environmental impact.

One of the reasons I like this class is because I feel like — maybe more so than environmental law — I can have an impact on the environmental side of things.

It’s a pressing need for us as a society to study and figure out as many of the environmental dilemmas as we can. I feel like a lot of the kids I work with are the people who are going to do it. Even for the kids who aren’t going into the environmental fields, this class gives them a perspective that changes their behavior.

More often than not in my classes, I’m certainly not the smartest one in the room. But I get to create the space where the kids are having conversations, digging into these issues, and hopefully getting inspired somewhere along the way.

I am the conductor, and for me, that remains a very satisfying role to play.

–Lance Powell

Science Teacher in Sequoia Union High School District

Atherton, CA