My mom came to the U.S. from India. She got a scholarship to do her PhD in French at UCLA, and then she adopted me from India when I was six months old. It was a huge family occasion — they all banded together to help me to come to the U.S. I made it here, and then it was just the two of us.

It was just my mom and me my whole life. She was an English professor at an online university. She made the sacrifice to leave tech and do something that allowed her to be at home with me at the end of the day. She had freedom, and I had the sense that teaching was a family job.

The library was my happy place. I would bring armfuls of books home, and I would finish like 30 books halfway through the week. So every time, my mom would tell me to check out more next time. It came to the point where I couldn’t even carry the books that I wanted to read; I was so excited.

Every summer, I would do the reading program, where you track the number of books you read. One of my core memories is getting my reading sheet stamped by the teenage volunteers when I was eight. I felt like I was so good at reading because I won free pizza.

My fourth grade teacher, Miss Branch, is the reason I became a teacher. I was the new kid in the class, and she was so bubbly. I wanted to be like her.

When I was older, I volunteered in the children’s department of the library. I loved that job. Every Friday, I would go and help out. The library closed early at six, and we would set it up in the quiet. I decided, ‘I want to be a librarian or a teacher.’

I grew up in California, right next to the Apple headquarters in Cupertino. It was stressful, and my school was highly competitive.

I had a teacher in high school who made fun of my skin color. It was AP Stats, and he gave an example of how if we looked at all our skin colors, mine would be the darkest. He pointed at me and made a joke at my expense. I don’t even remember the joke, but I remember feeling the humiliation of being the brunt of his joke in the middle of class and feeling embarrassed about having dark skin. I called him out at the end of the class — privately — and I said, ‘Hey, that comment wasn’t really cool.’ He said, ‘Okay, sorry.’ In my yearbook at the end of the year, he wrote, ‘Haha, remember that time you called me out? Good luck.’

That same year, another teacher made a remark in class about survival of the fittest. He said, ‘If we paired the fairest person with the darkest person in this classroom, they’d have great children.’ And he pointed at me. He said, ‘If you’re stuck on an island, what are you going to do to survive? You’d procreate with her, because the darker the skin, the easier you’ll survive in the sun.’

My friends and I were shocked, and everyone was kind of laughing hesitantly because they didn’t know how to react. I laughed it off, but the more I thought about it, the less comfortable I was. It’s a super taboo thing in Indian culture to be dark-skinned vs. fair-skinned. I’d never felt any stigma towards it until my teachers pointed it out my senior year, and then I felt wildly uncomfortable. I didn’t understand why they thought it was acceptable to make those comments.

Being a teacher is powerful — you’re in a place of guiding people. So when that happened, I thought, ‘I will never make a child feel terrible for things they can’t change about themselves. I’m not gonna let that happen to any other kids.’

I went to University of California, Riverside. When I was in college, we had an AmeriCorps group called the University Eastside Community Collaborative. The goal was to help students in Riverside’s Eastside improve in math and language arts.

I worked part-time in a second grade classroom. The experience was wild, because you go north in that part of California, and everyone’s rich, and everyone knows all the numbers and letters — but then you go south, and the kids don’t know how to read. The experience was so different. I had trouble fathoming that they didn’t read books at home. But the more I worked with that population, the more I understood the experiences they were going through, and the more I realized everything my mom had done for me.

There is a cycle of poverty. We’re going in circles. Because if someone’s not educated, they’re more likely to have kids when they’re young, and then those kids are placed into the public education system and don’t have extra supports at home. Maybe they help their siblings, so they’re doing extra work, and maybe their parents aren’t at home, because they’re out working three jobs to sustain their children. And then those children don’t necessarily get the support they need from the public education system. When they grow up, they find themselves in the same situation their parents were in.

The endless cycle of poverty frustrated me. How could we let this happen?

I was tutoring a small group of kids, and I fell in love with them. I decided I didn’t want to teach in a posh neighborhood. I wanted to teach in a neighborhood where kids could benefit more. Because where I grew up, kids go to Kumon, they go to Sylvan Learning, they do ACT and SAT prep… all those extra supports are in place. But the kids who don’t get that, what about them? Who’s going to take care of them?

I remember talking to the teacher whose classroom I was helping in, and she said, ‘It is what it is. You try your best and you help them, and sometimes they come back later and say, ‘You helped me.’ But sometimes you see them later in life, and they’re not where you thought they would end up. And that’s life.’

My journey to teaching wasn’t easy. My family wasn’t necessarily supportive of my wanting to be a teacher. I had to take a gap year right after high school because my GPA wasn’t high enough to apply where my family wanted me to go, and they thought I would benefit from going to India instead.

I wanted to apply to college at the same time as everyone else. I tried to apply on my own with the help of my guidance counselor, but ultimately that didn’t pan out, and I boarded the flight to India a week after I graduated from high school.

I don’t want to give my family the credit for it, but I had a really nice time in India. It turned out that I loved being around family. I now fully understand how to get on a bus and go places in India by myself… I learned to do things on my own. I volunteered in a Pre-K classroom with Indian students. It was definitely a pivotal experience.

I tried a tad bit of college there. I didn’t understand the system, and it didn’t work out for me. After that, I felt like my family was saying, ‘Look, if you mess up this time, then you’re going to be a failure. You’re not incapable. You’re smart. But if you don’t pull yourself up by your bootstraps, then there will be a time in life when we cannot support you.’

I applied to all the colleges. It was a nerve-wracking experience. My highest financial aid offer was from UC Riverside, and I ended up going there.

And then I was like, ‘You know what, I’m gonna really put my mind to it.’ And so I graduated in three years, to catch up with my peers. I double majored in creative writing and education. I was like, ‘Take that!’

It’s rough out here. It’s not the pay. I can tell you right now, for me, it is not the pay. It is the lack of concern, compassion, empathy, and support. People choose to have one, two, maybe three, four, or five children; I’m in here with 26 five-year-olds, and many aren’t used to discipline.

When families were trapped at home during COVID, many children were put in front of a device playing Cocomelon. They got even earlier access to the internet. And the internet is not regulated for five-year-olds. Students are out here cussing at five years old because they saw it on social media. We’re seeing a drastic shift in social-emotional skills and behavior. I would say that one of the leading causes for teachers leaving the field today is behavior and the lack of accountability.

From what I can tell, the behavior has gotten worse, but administration’s ability to hold students accountable has diminished. Admin’s hands are tied because when we lose enrollment, we lose funding — and when we hold kids accountable, through suspension or otherwise, parents un-enroll their kids.

My belief is that if your kid wants to clap back, you have to be real with them and hold them accountable, because otherwise they’re not going to understand that actions have consequences. If a child in my classroom hits another child, they lose recess time. That’s how I keep children safe. I am not just going to give them a warning — if they hit, they lose recess.

And consequences can be positive too, right? If you get X done, you’re allowed to do Y. We have to remember we’re the adults in the situation. They are not our besties. You can have a really good relationship with your child, but they should not be able to run the house, because they are not ready for that responsibility. Trust me, they want you to be in charge.

I’ve had a couple of behavioral issues. And when I tell the parents, they’ll say, ‘Yeah, I tried to take away the iPad at night, but he just takes it back.’ I’m like, ‘What do you mean, he takes it back? Put it somewhere else. He is five years old.’

One of my students drew on her table the other day. I said, ‘You’re going to clean that up, or you’re going to lose recess.’ And then she sat there and threw a fit. It would have been easier for both of us if she’d cleaned it up, but she didn’t, so I had to follow through.

I took my kids out to recess and left someone to watch her. I didn’t leave her alone. I called the counselor, and the counselor talked to her about her feelings throughout recess. I came back and she was still crying.

I brought my voice low. I said, ‘Look, you have 10 seconds to clean that up, wipe your face, and go to lunch. Or I will carry you to the principal’s office.’ She cleaned it up. That’s all it took. Because she knows I follow through on consequences. And that’s what I mean. You can be loving and set high expectations. You can be strict and help them be a better functioning human being in this world. It doesn’t help them if you don’t challenge them. If you’re not going to expect the best from them, you can’t expect the best for them.

In that moment, she knew I wasn’t going to play with her. I didn’t rub it in her face. I said, ‘Thank you for cleaning it up, let’s go to lunch.’ She wiped her face and went to lunch. She was happy the rest of the day.

I want to show the kids that I believe they can touch the sky and keep going. It’s that belief that carries me through my teaching experience. And that belief wasn’t necessarily formed when I was younger, but towards the end of my educational experience I figured out, ‘Wow, if, if you have high expectations when they’re younger, they’ll want to reach those expectations and show you.’

I feel like every teacher has that one kid, where it’s rough and you feel low — and then, whoosh, they grow. It’s because of the nurturing and the loving and the high expectations.

I love teaching hands-on learning. If the kids are going to learn about a tomato, I want them to pour the water, and I want them to understand that this thing is going to grow under the right elements. I want them to experience learning, not just ‘my teacher told me one plus one equals two.’ I want their learning to be interactive.

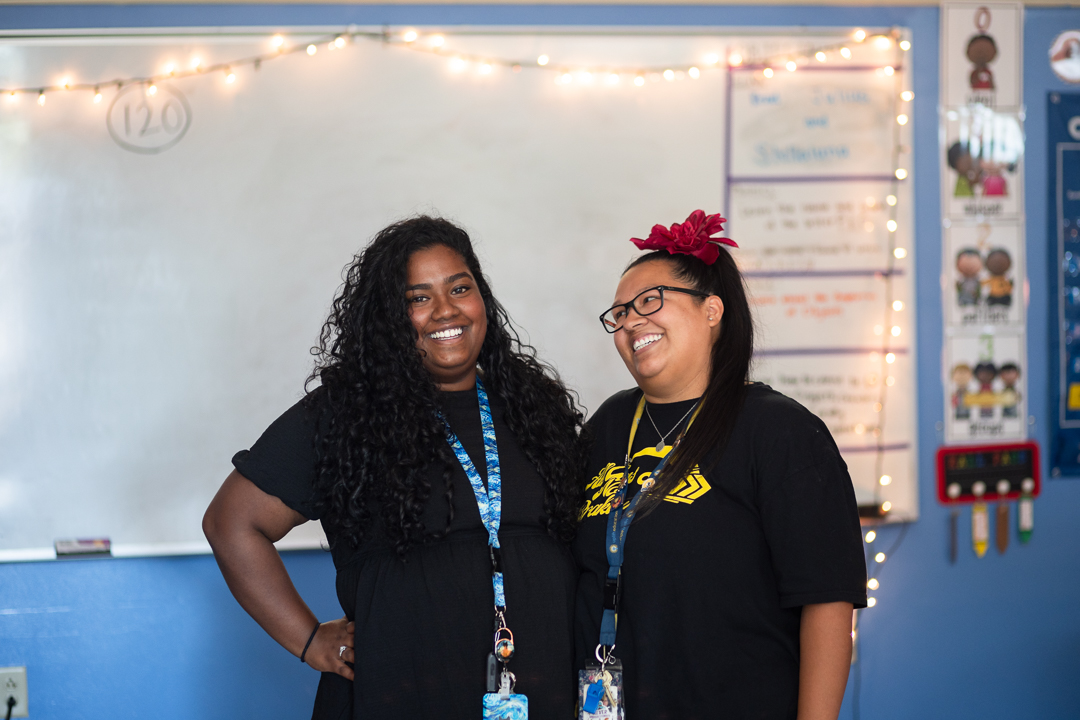

So it started out with just plants. I was the plant lady. And then halfway through the year, I found out Ms. Flores’ husband really wanted a bearded dragon. I was like, ‘Perfect. We can have a class pet. And then he can help the kids grow, and at the same time have a loving and stable forever home to be in!’ So I said, ‘Hey, Ms. Flores, if I buy a dragon and his tank and his equipment, will you take him home on breaks?’ And she said, ‘Yes.’

I did a lot of research before getting Iggy. He’s not from the pet store. He’s from the DFW Reptarium and is responsibly sourced. We taught the kids all about bearded dragons before we got Iggy, and they had no idea he was coming. I surprised them on a Monday, and they were so excited.

The kids show so much ownership over Iggy. The older kids come in here just to look at him, and my kids say, ‘He’s a bearded dragon. Did you know that they’re from Australia? Did you know they eat crickets?’ They go home and talk about him. They do research with their parents.

My kids from last year come in to say hi to Iggy. He means a lot to not only my class, but also to other kids at the school. We’re in the middle of the city, so it’s special to have nature in the classroom. Sometimes teachers will send their kids to calm down by looking at Iggy. If they do really well, sometimes they get to hold him or feed him a mealworm here and there.

He’s the star of the show.

When I first started here last year, we had four classrooms and four kindergarten teachers. This year, they condensed us to three and moved one teacher out of kinder, so we all got more students. As part of that, we got Ms. Flores as a teacher’s aide. I love her.

Ms. Flores makes my life so much better. Don’t make me look at her because I’ll cry. Just having a human being around who has empathy… she has done so much for me, just by being herself. She has no idea how much she means to me.

The school had to cut a bunch of the teacher’s aides, so I’m lucky Ms. Flores is still here most of the time. She’s the head TA, so she’s pulled all over the school to do other things, but her homebase is here, and that makes me feel like her presence is with me throughout the day.

Last year was my first year of teaching. Those babies will always be on my brain. I had a kid — let’s call him Rob — who had trouble making connections. I would say, ‘Hey Rob, come over here!’ And he’d say, ‘Me?’ And I’d say, ‘Is your name Rob?’ And he’d think about it and say, ‘Yeah, I’m Rob.’ The connections were just not connecting.

He would sit over there in the front, and he had trouble controlling himself. As a teacher, it felt hopeless. I worried he wasn’t understanding anything. We would go over the sounds that each letter makes, and by mid-year, he was still making the wrong sounds.

I kept consistently working with him. It made me sad. I was depressed. I kept trying to get through to this kid. At the end of the year, something clicked in his brain. All of a sudden he said, ‘I know what one plus one is!’ I was like, ‘What is it?’ And he said, ‘Two!’

I gave him more math problems. He seemingly didn’t even know how to identify the numbers five minutes ago, and now he was adding. He was doing it. And he was so proud of this work. Seeing how proud he was made me tear up. It was amazing.

He was definitely still lower than where he should have been, but any progress is progress. That’s what I believe in. He grew. He did his work. And he tried his best.

You feel this overwhelming love and pride when they get it.

I got Rookie of the Year last year, which is like Teacher of the Year but for first-year teachers. My boss’s boss’s boss came in and observed me on my first day. And every time he’s seen me since that first day, he says, ‘I remember when I came in on your first day, you looked so scared. And then I came back the next time, and I didn’t even recognize you. You turned the whole class around.’

I have a strong sense of ownership over my class — a sense of pride. I believe in all my kids and I hold them to high expectations, because I know they can get there. And if they act like a worm in the hallway, I will not accept it: ‘You know the rules, you know the expectations, so fix it, and we can move on from it.’ When you look at my class from last year, they are thriving in first grade. They are set up for success and they know the expectations.

Now, I don’t know if that sense of pride will stay with them forever. I’m only one teacher. But what they learn in this classroom is magical.

I have this one picture from last December. They’re sitting in front of the tree looking at each other, smiling. That’s the picture that will stay forever in my brain. Because the things that they felt in this classroom were real. They knew this was different.

They were proud to be in this classroom.

–Kritika Srinivasan

Teacher at Uplift Williams Preparatory

City Teaching Alliance Fellow, Cohort 2021

Dallas, Texas