At first, I didn’t want to be a teacher. I come from teachers. My mother’s a teacher, my grandmother was a teacher — on my mother’s side, there are teachers all the way back to slavery. I grew up in a classroom, helping my mother set up for first grade at the beginning of the school year. I didn’t want to do it.

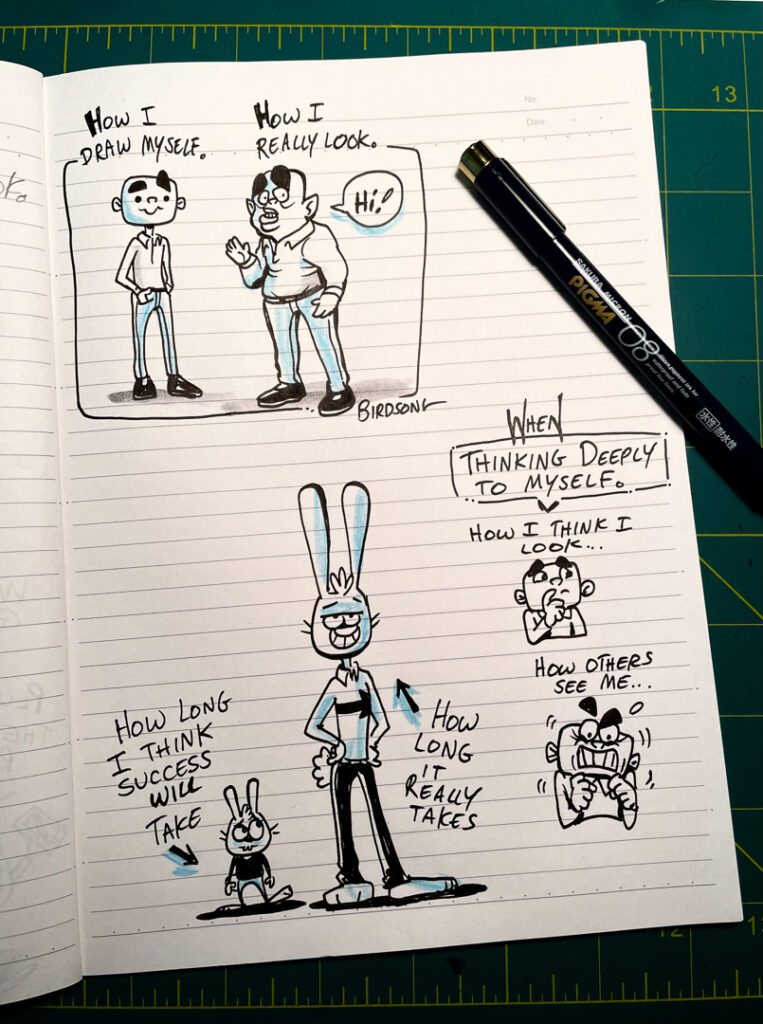

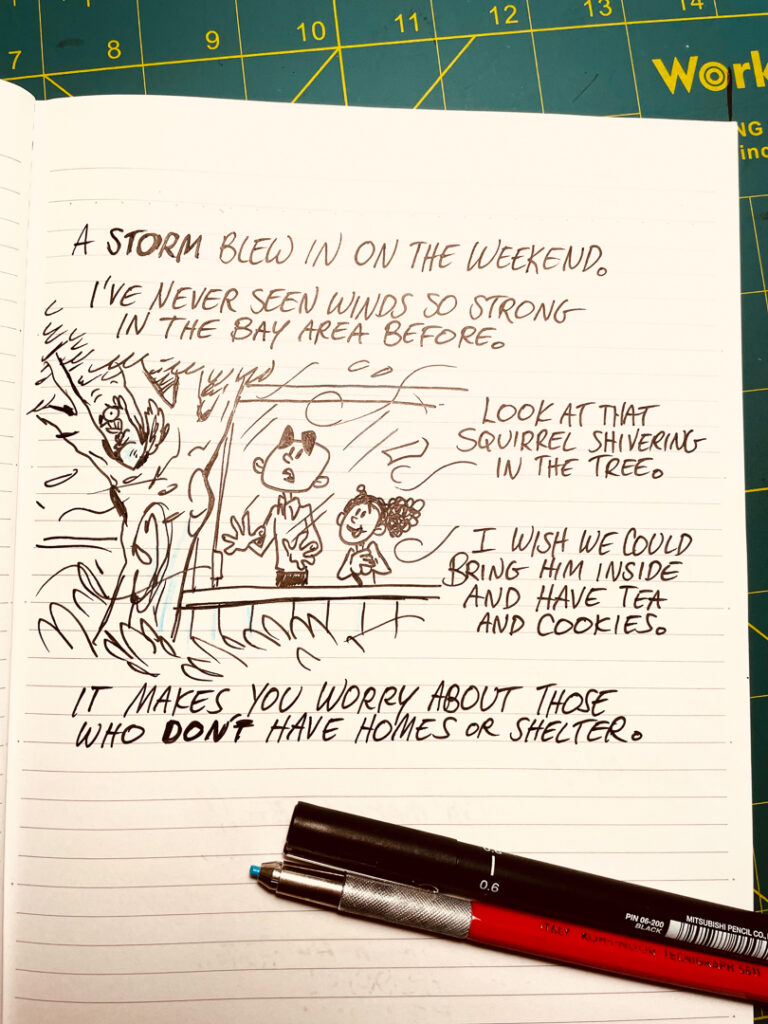

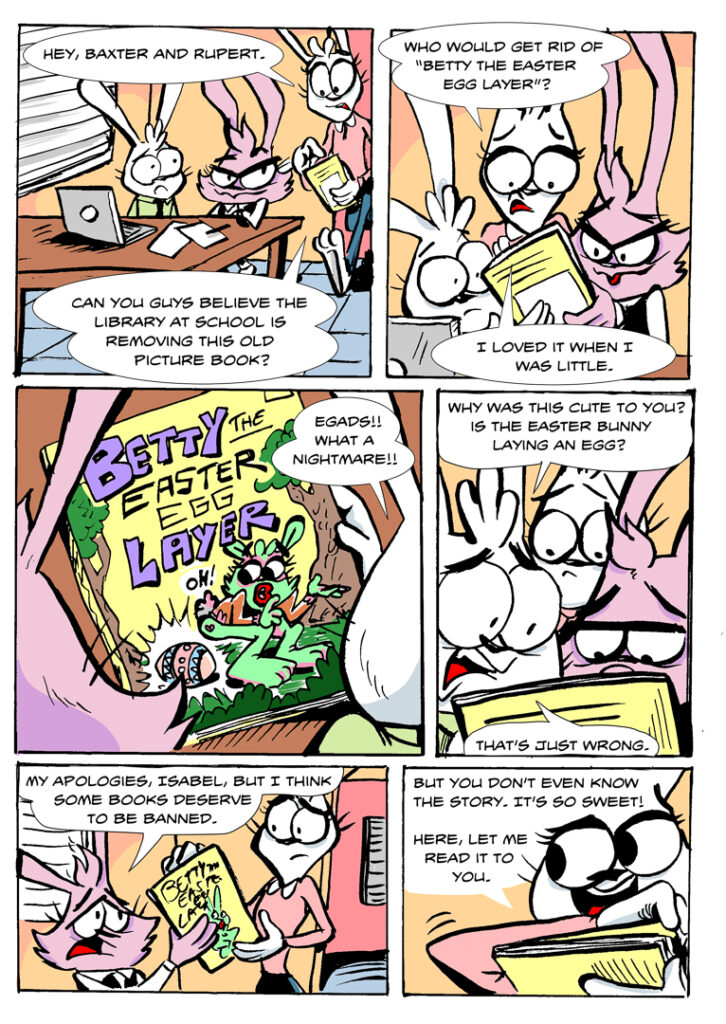

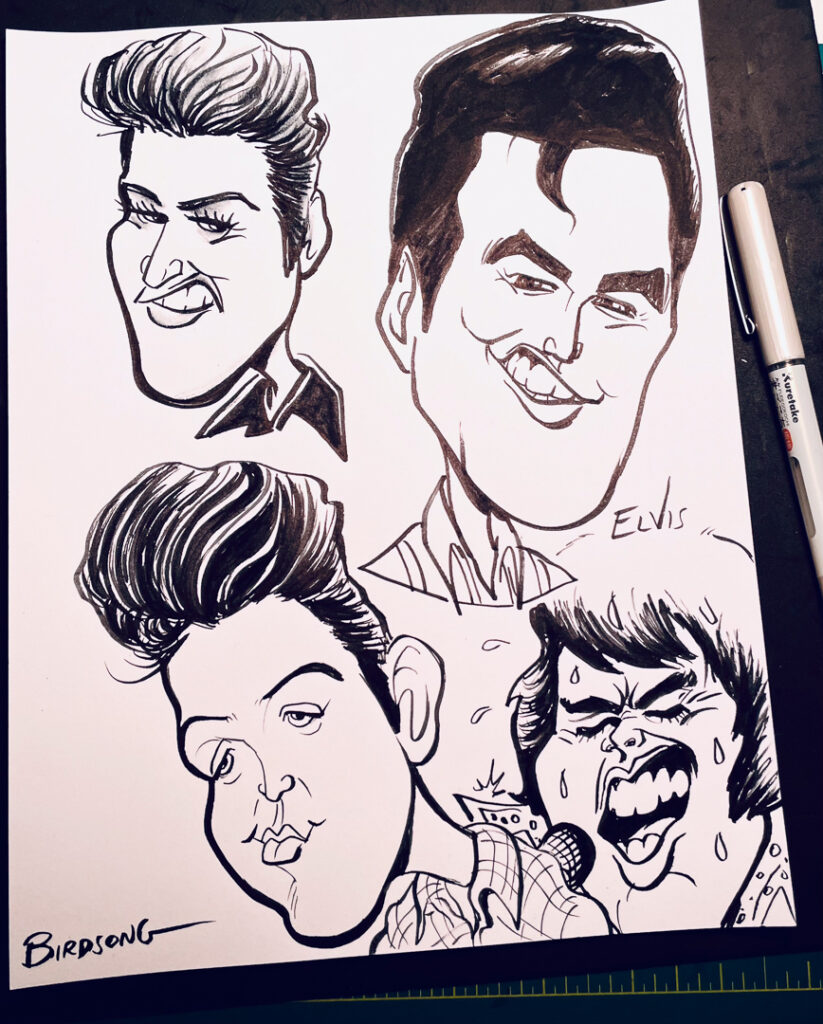

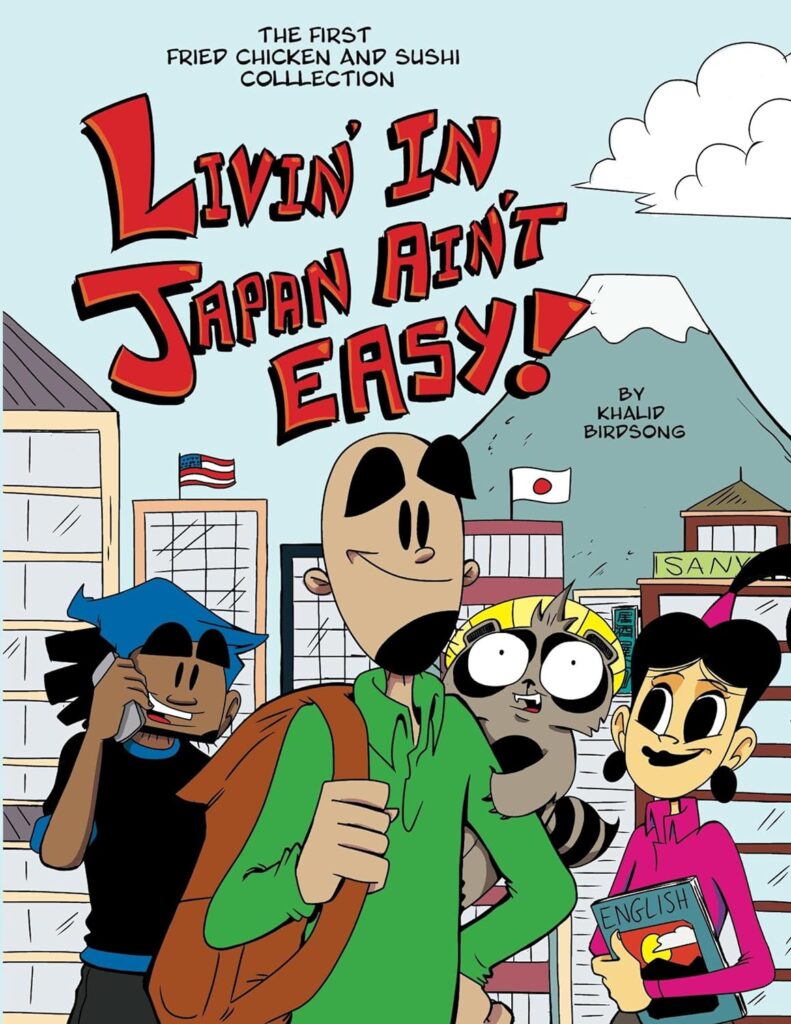

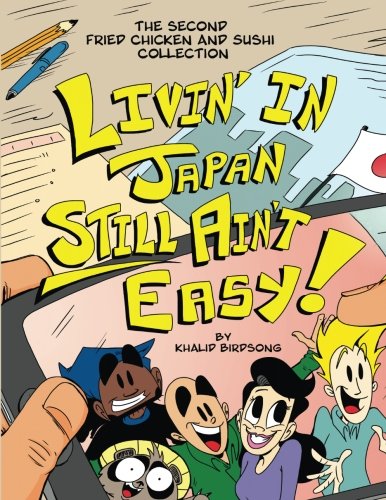

I wanted to work in comic books. There’s now a huge market for graphic novels and stories about regular life, but when I was a kid, it was mainly superhero comics. I wanted to do comics like what you would see in Europe or Japan, but we didn’t have that here. So, I worked hard to try to get into superhero stories, but I didn’t love it as much.

I ended up moving into illustration, and at Howard University, I ended up getting a degree in graphic design. Then I was a freelance illustrator and cartoonist, but I needed some more regular income, so I taught in afterschool programs. I made decent money working part-time, and I enjoyed doing that. I enjoyed working with kids. When they finished their homework, I would do a cartooning class once a week and show them how to draw. And then I actually liked that, too, which was surprising to me.

I thought, ‘Okay, I like this, but I’m not going to be a teacher. No, no, no.’

I moved to Orlando, Florida. I was still freelancing, but I got a chance to teach in a very large public school, and I ended up falling in love with it. It kept surprising me — not only that I loved working with the students, but that I really liked to break down how to create art. I liked the ‘how to’ part. I loved getting to know the kids, helping them learn to create, and seeing the magic of that. I really got hooked.

Over the years, I’ve changed how I feel about teaching, and I see it as another art career.

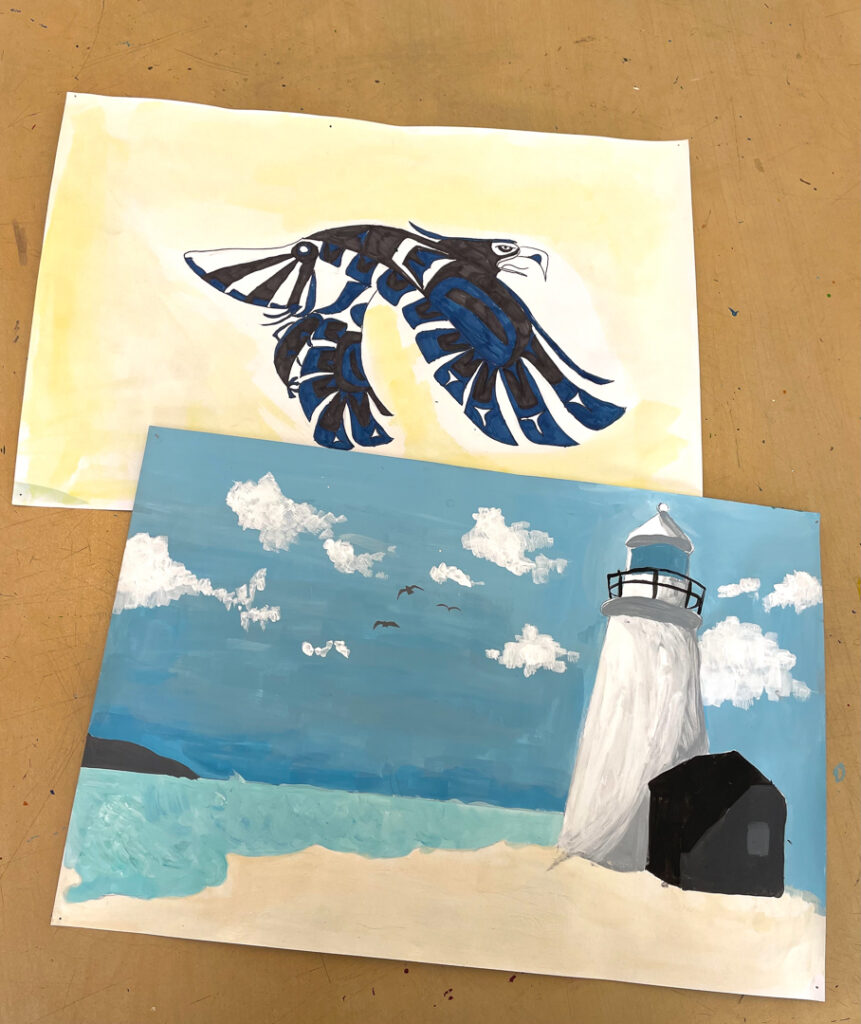

In order to make a comic, you have to know color theory, and you have to understand so many different parts of art, so drawing comics makes it easier for me to break art down for my students. We learn about everything here, from painting to drawing to sculpture, but I think that my start in comics really helps to share it with the students in a way that is fun and easy to understand. They learn how to draw a person’s head from multiple directions and how to do it on their own without any reference. In comics, you have to learn how to draw a lot from your imagination or your memory. I try to teach students to create what they care about.

Some years ago, I was teaching a fourth grade student who I’d taught since kindergarten. One day, after a lesson, he had this flash of realization: ‘I get it! What you were teaching last year and the year before, I see how it’s helping me now.’

I was so excited because most students don’t understand scaffolding and that you’re building on something. But he totally got it. And he was like, ‘Oh, yeah, if I didn’t learn this other thing before, I wouldn’t be able to do this.’ I told him, ‘That’s right. That’s why we do it.’

That’s one of the benefits of being an art teacher — I get to teach them every year. And I’m a part of their growth. I’m planning everything in advance so they can build on it.

That student solidified the value in my teaching. And anytime a student says thank you for teaching them, I love that: ‘Now I know how to do this because you helped me. You paid attention to me.’ That helps me know it’s sticking. I’m doing this. There’s something that’s working.

At the beginning of each school year, I have the students draw a self-portrait, so they can see how they grow over time. It helps them see, ‘Wow, I didn’t understand how to draw eyes last year, but now I do.’

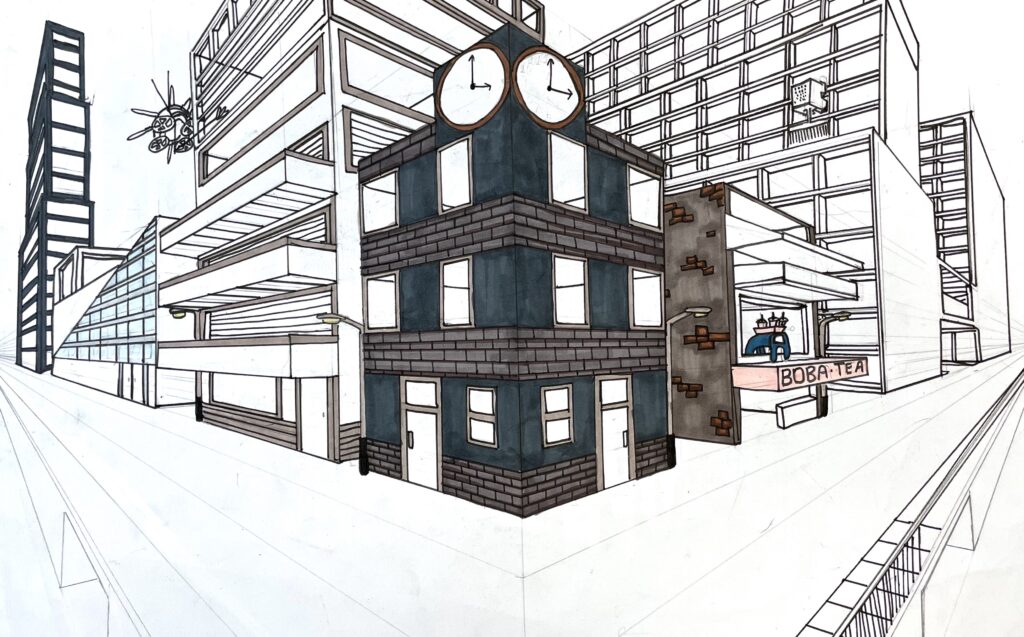

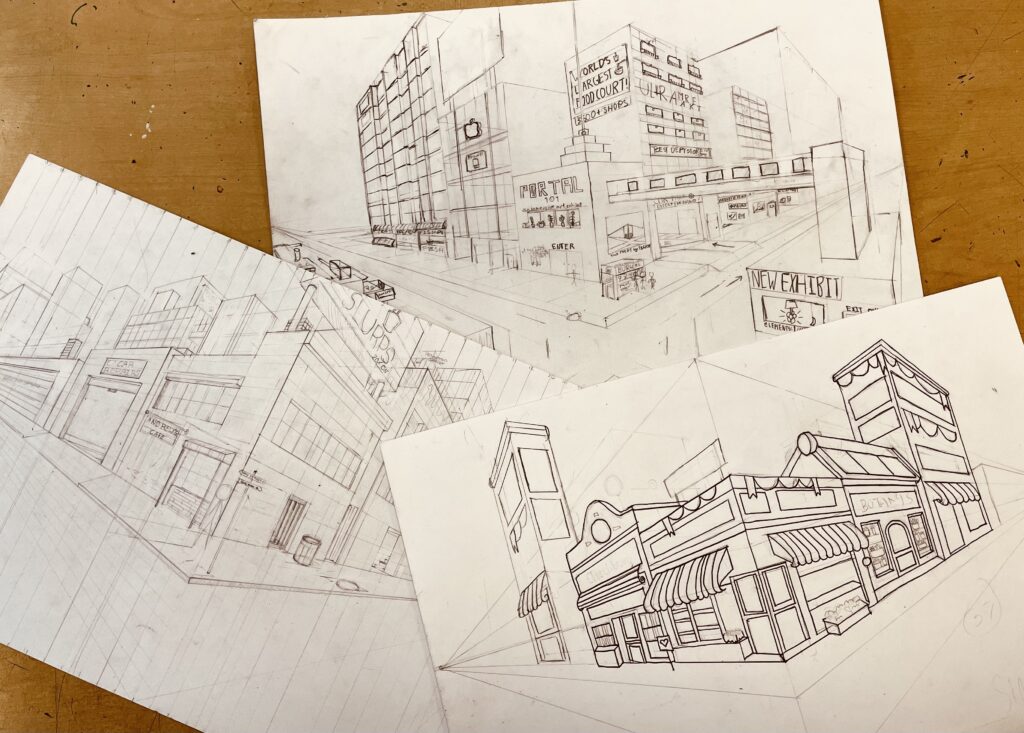

We do the same thing with drawing buildings: learning to use one-point or two-point perspective. In sixth grade, they draw a street corner; they have to learn not only the technical aspect of drawing all the lines but they have to learn to see. Their brain wants to mess things up, or the angles want to go wrong, and they have to learn to see the three dimensions on a flat piece of paper. Once they learn to see, it helps them with everything else they do. They start to say, ‘Oh, I see what happens here. When something goes further away, it gets smaller.’

That’s really what art is: learning to see.

You know the classic thing of making a sphere look round, where you have to shade darker on one side and gradually get lighter, for value? When you show kids something like that, they get excited, and there are countless times when they’ve started jumping up and down.

I always tell the students to go home and teach someone in their family what they’ve learned, because it’s how they’re going to remember. One of my students did that, and their parent emailed me so excited about what they were learning. A different parent came in and told me how happy they were that their kindergartener was learning how to draw a horizon line. That simple idea ended up opening up her whole world. That student is in high school now, and she’s an amazing, phenomenal artist.

When I taught kindergarten, a lot of that stage was about learning to see shapes. I would say, ‘Look around the room. How many rectangles do you see?’ They would point out the door, the window, the table. And I’d tell them, ‘If you learn how to draw a rectangle, you can learn to draw the human body because it’s made up of shapes. You just have to see shapes in everything.’

Then they have less fear about drawing because they learn they can break it down into shapes and add details on top. Every year, even in eighth grade, I’m trying to remind them to take a look: ‘This is a basic shape, and you don’t have to be afraid of it.’

The kids get sick of me saying it, but I always say that artists are thinkers. When you’re drawing something, you have to think through what you’re presenting, even if it’s something abstract. You have to choose the colors, how you’re going to put them on the page, and where they’re going to go in your composition. Once students own that, then there’s a lot of power, and then they feel like, ‘I can do this. I am an artist.’

If you create something and it doesn’t work out, you can create something else. Kids learn that whole process is a part of it. It takes work to create, but students get excited about the fact that they are capable of doing it.

Art transfers to everything else that they do. No matter what career they go down, they’re going to need to think creatively and learn to connect different ideas. They’re going to need the confidence to create something out of nothing. I don’t expect for them all to become artists. But I think that the artist way of thinking and understanding will move through everything that they do. I think it will help them in any area of life.

Having administrators who are supportive of you makes a huge difference for teachers. I’m fortunate to have an administration and a community that supports the way that I teach the curriculum, and if there’s any issue, they will talk through it with me. If a project doesn’t quite work, I can change it. There’s flexibility.

And then I think that this is a hard thing to create, but: an inclusive culture is huge. Having faculty and staff who support you, without cliques… where you feel comfortable being yourself… it’s invaluable. I feel like I can bring my whole self to school and be myself with parents and in the classroom. I am in a community, but I get to be my own person. There are other schools where it just isn’t always like that.

So I think those are the two biggest things that keep a teacher like me in a school: support from administration and an inclusive community that makes me feel like I can shine.

I taught for many years, and then I started feeling tired of my career. I felt like there was nowhere for me to go, whereas if I were working at a corporation, maybe I could climb some sort of ladder or get to some other place. I thought, ‘If I’m going to be an art teacher, I’m going to be an art teacher forever unless I want to go into administration, which I’m not interested in.’ And that really got to me for a while.

In college, I’d done an internship in New York as an advertising copywriter. I thought that was interesting. I felt like if I could get better at writing, then it would help everything that I do, including cartooning.

So I left. I worked for a medical device company as a copywriter. It wasn’t very creative, but I was at least writing all day. It was exciting. I learned a lot. But I missed the creativity. I also felt that what we were doing was important in its own way, but it didn’t feel the same way as teaching.

Then, the pandemic came, and my job was cut. The art teacher who had been teaching here at Keys was a friend of mine, and he passed away from cancer. It was really hard. The school reached out because I’d taught here in the past, and they asked if I’d consider coming in.

This is a community, and I’d kept up with a lot of the teachers — they were some of my best friends. It felt like a family business where an uncle I loved had passed, and they were asking me to come in. I thought, ‘I’ll come in and see how it goes.’

The only thing is, it was still the pandemic. So I wasn’t coming back to teach in the way that I had before. I was trying to teach art on Zoom. I had to totally relearn how to teach. I learned new skills, but that first year was really hard… having to package up and send art supplies home to students.

For all of us, as teachers, it was difficult.

The students had to take pictures of their art and post them online, and then I had to go in and write comments for 140 students. Normally, I could just walk around the classroom and give feedback and encouragement, but I couldn’t do that. It was tough.

But I will say that the pandemic gave me a deeper appreciation for in-person teaching.

When my wife and I lived in Japan, I noticed that teachers are more respected there. Even just the word ‘sensei’: it means teacher, and it’s used to refer to any person of authority. You call a doctor sensei in Japan, and you call a teacher sensei too.

But in Japan, as well as here, teachers burn out.

Even for people who want to keep teaching, it can just be too much. Sometimes, you want to try other things, especially if you’ve never done anything different. I think that my story shows that you can leave education and you can come back into it. There’s nothing wrong with going in different directions. It’s okay to be flexible and to try different things in your career.

If you want to try something else, it doesn’t mean you have to close the door on teaching. You don’t need to decide you’re never going back.

Things change. Your point of view might change. You’re never stuck.

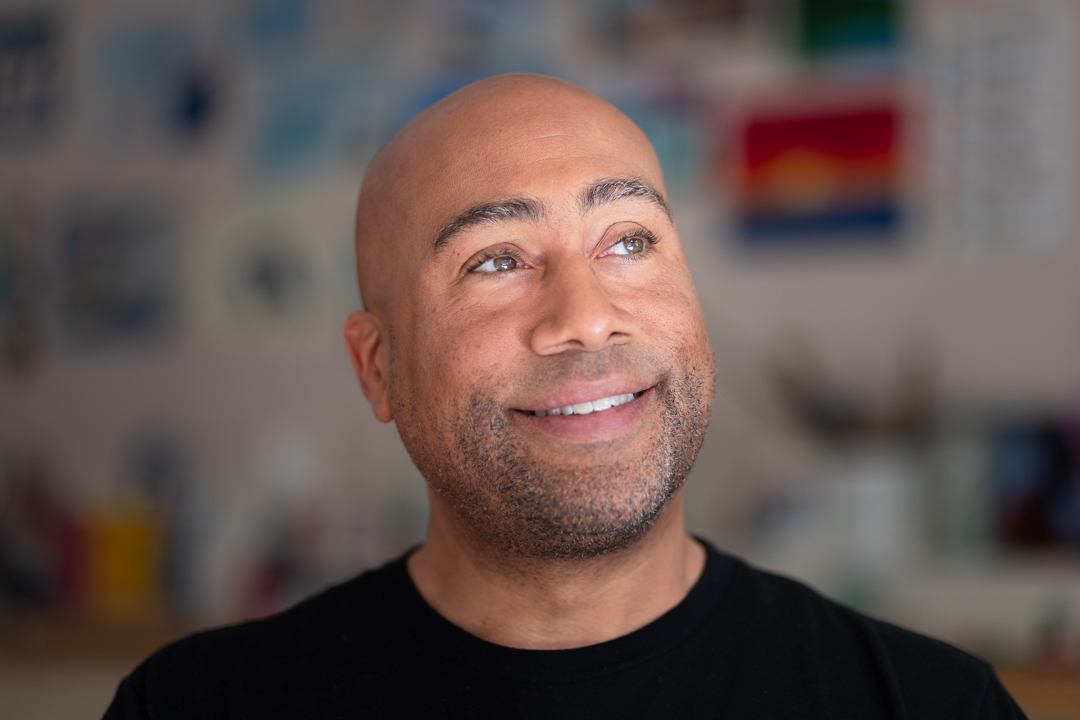

–Khalid Birdsong

Teacher at Keys School

Palo Alto, California