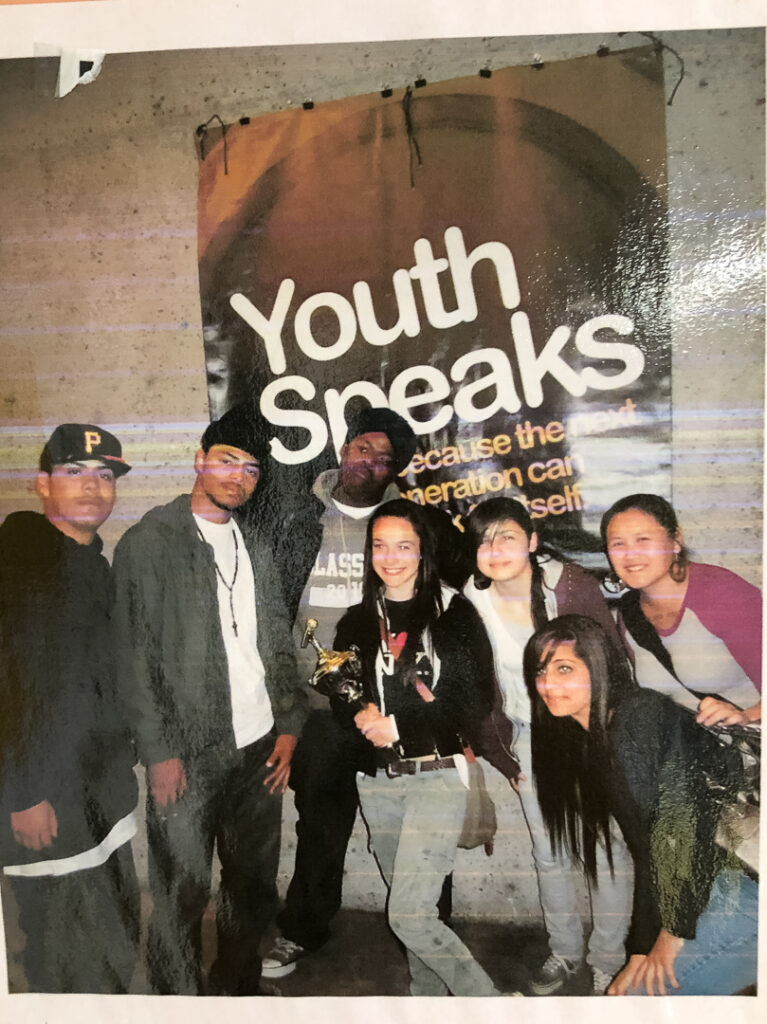

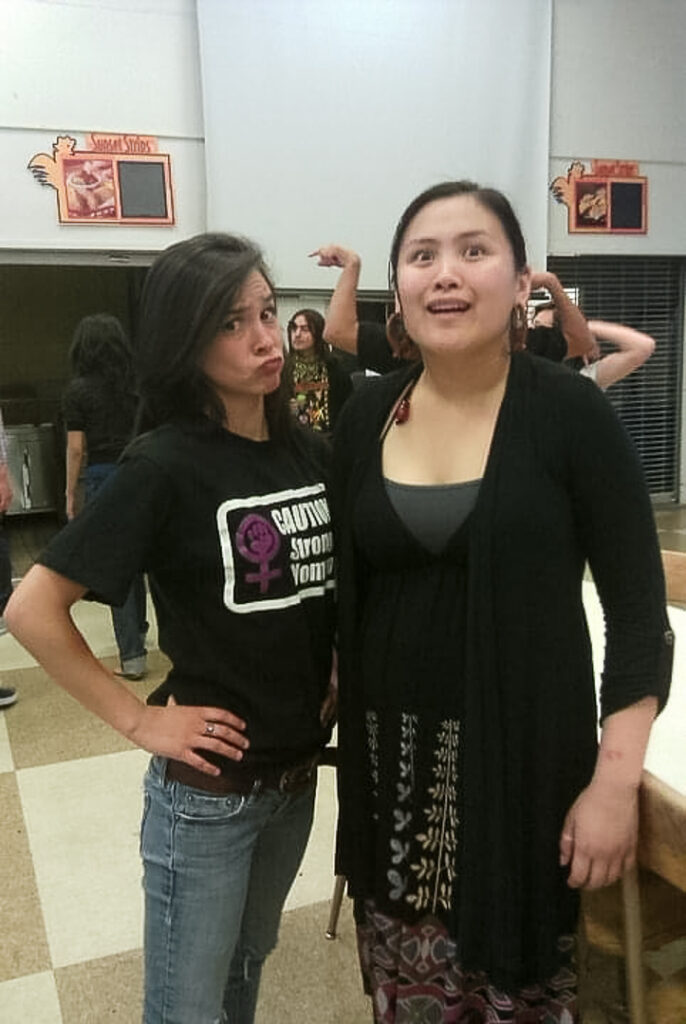

I went to high school here in San Leandro, at the school where I teach. We have three ‘academy programs,’ where students can apply to go through 10th through 12th grade in cohorts focused on multimedia, business and finance, or social justice. I was in the cohort called Social Justice Academy, so I took my history, English, and elective classes through the lens of social, political, and environmental justice.

My teacher in that program, Erica Viray Santos, was the most incredible teacher — she still is. She taught us how to ask critical questions about the world. I remember sitting back and watching the way that she interacted with students, and feeling the relationship that she and I had as teacher and student. I knew that’s what I wanted to be. I wanted to impact students the way she impacted my classmates and me.

That program helped me understand the importance of teaching critical consciousness, empathy, and compassion. I felt a sense of responsibility that there needed to be more teachers who did what she did.

I thought a little bit in college about doing something else, but I always came back to the joy that I get working with young people. I always came back to my desire to help with that ripple effect: letting young people find in themselves what we already know they have — this inherent power to be good and to do good.

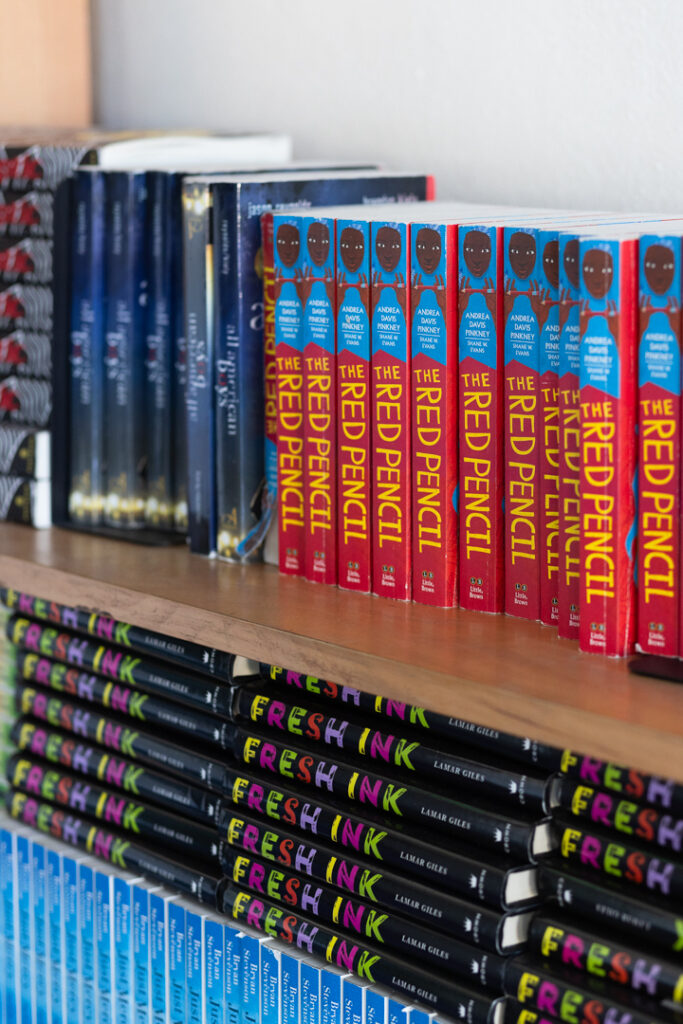

My initial choice was to be a history teacher, and in college I thought I would major in ethnic studies. But as an undergrad, I got into speech and debate, and that led me to communication studies. I realized how much I loved writing and how teaching English would give me the flexibility to authentically talk about issues and events with students. There’s an openness in teaching English. A lot of students gravitate towards their English teacher for exactly that reason.

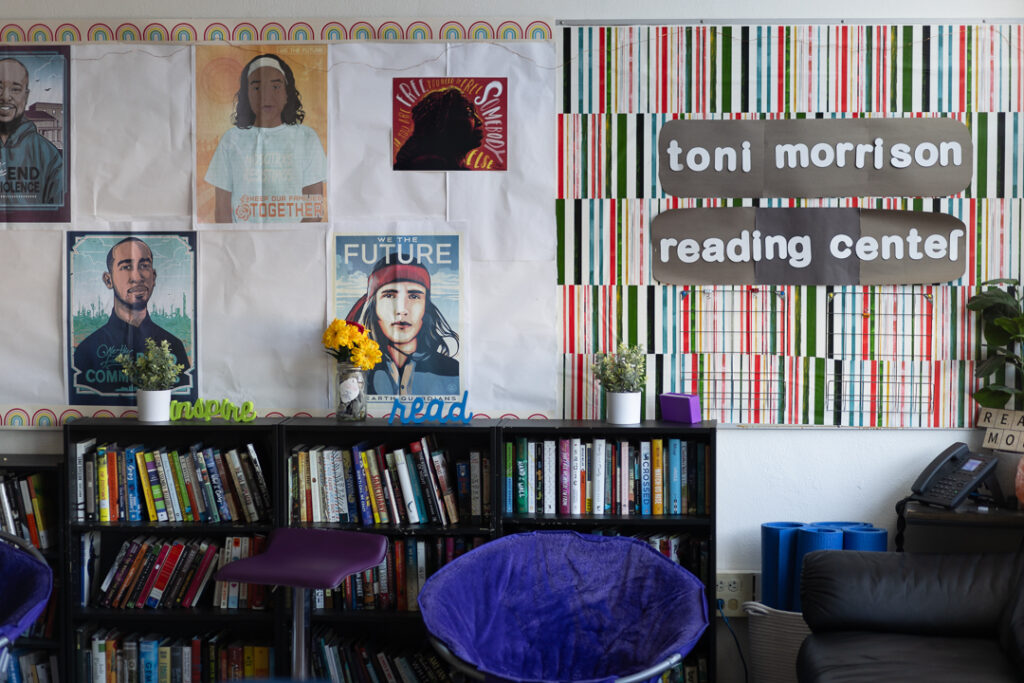

English teachers believe in exposure to stories and experiences. Literature builds empathy and compassion, and that translates to our students. I gradually realized how special an English teacher can be, and that’s what I chose to do.

I love my community. I had a great experience here as a student, and even then I had this vision of coming back and teaching here. I wanted to work in the place that transformed me. So even before I taught here, I coached the cheerleading team throughout college. Coaching cheer solidified that I wanted to work with teenagers and with the teachers here, and it allowed me to stay connected.

I didn’t start my teaching career here, though. I got my credential right after Donald Trump was elected, and there wasn’t a job opening here at that time. I took a job in another Bay Area district that’s a bit more affluent and less diverse. I was a little disappointed that I couldn’t teach where I wanted to, but as a white woman I felt an obligation to teach other people with privilege, especially following that election.

I have a vivid memory of sitting in a department meeting there. I was young and eager to collaborate. Everyone was going around and sharing what they were doing in class, and then it was my turn. I was excited to share about an essay my students were working on: they had just read ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ and were writing about the role that savior complex plays in the book — the choices Atticus makes and what they think about his choices. I remember looking around and seeing all of these confused faces. A colleague said, ‘That sounds cool. But it doesn’t sound like you should be doing that in English class.’ And it reinforced for me that there’s a huge disconnect about the role of the teacher — not only with people outside of the teaching profession, but also a disconnect between teachers from different backgrounds and different generations.

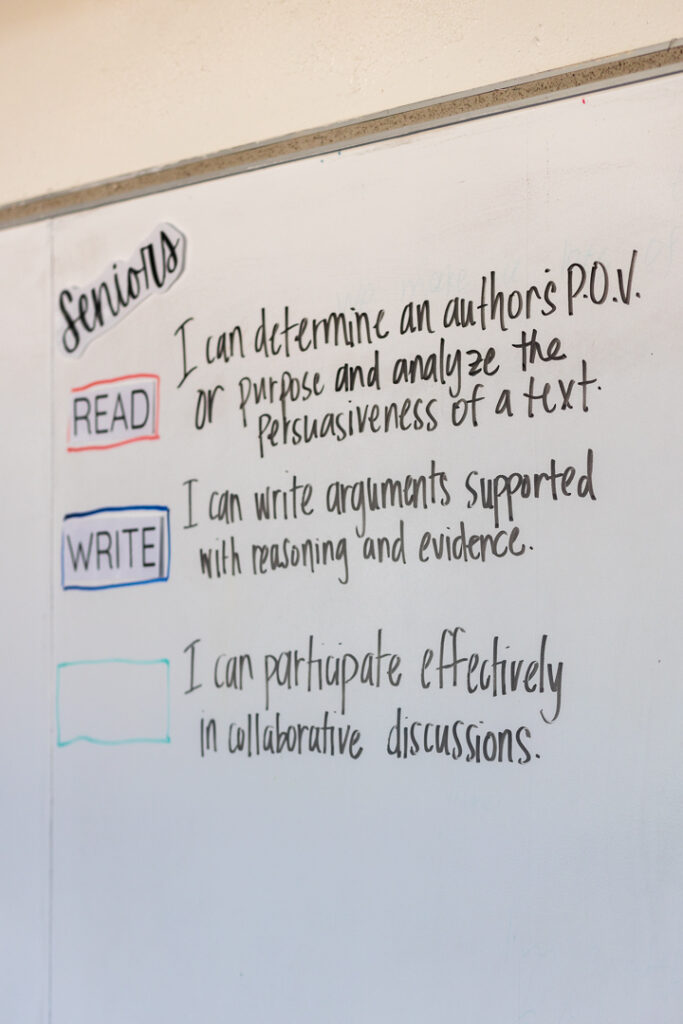

For me, teaching is about asking hard questions and encouraging critical thinking. It’s encouraging kids to connect academics to their own experiences, in order to learn the content but also to learn about the world beyond content standards. So in that moment, I was thinking, ‘The fact that you think this topic is outside the scope of an English essay means that something’s missing.’”

I knew there were teachers back here in San Leandro doing the work I wanted to do. So as soon as an opportunity came up, I made my way back.

Historically, we understand school as a place where students get basic knowledge. Right? You learn how to read, you learn how to write, you learn basic mathematics. School isn’t always a place where you’re talking about challenging things. I grew up being told that we don’t talk about money, politics, or religion at the dinner table, and for a lot of people, that idea carries into the classroom.

There is value in being aware of how you talk about those topics. They can be sensitive. Everyone has different experiences, cultures, and families. But I also feel like the reason why we live in a nation that is so divided, in many ways, is because we don’t know how to talk to each other about things that matter. If it’s not something we’re taught how to do respectfully and intelligently, we suffer in ways that go beyond academics.

And so I believe that we do need to give students resources for how to ask critical questions, how to research things on their own, and how to view things from multiple perspectives. We need to teach students how to understand that multiple things can be true at the same time. It’s a cultural shift. And as our nation becomes more and more divided, many teachers — especially younger teachers — feel it’s a teacher’s duty to give students tools to overcome that divide.

In the past, San Leandro was known as a Sundown Town: if you weren’t white, you weren’t out when the sun came down. This area has a deep history of discrimination and redlining. Being right next to Oakland has affected the way that San Leandro has grown and developed, with San Leandro residents historically trying to separate themselves from Oakland. My dad grew up here and talks about how you could stand at the border and see an immediate shift in the buildings, the homes, and the people.

Brian Copeland, a writer and actor who grew up here, has written about how San Leandro’s homeowner associations got together in the 1950s and ’60s to prevent homeowners from selling to Black families. Not so long ago, people in Oakland referred to San Leandro as Klan Leandro. Some people still do. But now our city is much more diverse.

Things have shifted a lot, but the people who lived through that experience are still here. Not everyone’s mind changed as our demographics changed. So there is still a lingering narrative around ‘letting these people in.’ Over the past few years, the city has been making space to name and acknowledge our history as a way to reconcile and move forward. I see a light at the end of the tunnel, though it still feels far away.

The administrators here are incredible. They’re very aware of how our city’s history and racial labels have harmed people in the past, and they actively work on how we reframe our roles as people so that we don’t center our race, but also don’t ignore how the way that we show up affects the space. It’s not easy. It’s very nuanced. I’m constantly still doing work to be aware of my positionality and the impact that it has on the work that I do. And I think that that awareness has helped me learn how to step up when it’s my time and how to step back and default to others when it’s their time.

This is my home, and I care a lot about it. I’m grateful to have awesome colleagues who are willing to support me and to figure out how I can help them, too.

I believe that any work of true activism is always going to come from a place of love: a love for humanity, a love for freedom, a love for what’s right. Love is a universal language that everyone can respond to. And oftentimes, people who are challenging ideas or systems are viewed as angry. Activists are viewed as coming from a place of hate or misunderstanding. And that initial gut feeling that you get from somebody’s anger can be the barrier that prevents conversation and prevents any progress from happening.

I often end up having conversations with people about what it means to them to ‘love your neighbor.’ How would you want your child to be treated? Because if you have the ability to empathize, then any conversation around justice shouldn’t be an issue. But it doesn’t always go well.

I met my husband when we both worked at In-N-Out Burger as teenagers. He grew up in a more conservative family, in Castro Valley. So when we got together, I was ‘fighting the power’ — and he was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ He was one of the first young people I interacted with who was willing to argue with me. Our interactions as kids gave me tools to think about, ‘Okay, how do I stop and listen to what other people have to say, even if I am repulsed by it? And then how do I empathize with this person enough to make progress?’

We challenged each other a lot. He helped me learn how to connect with people who are starkly different from myself. I’ve learned a lot about how to interact with my students who have different views, from being loved by someone who has different views.

When teachers talk about being overwhelmed, I know it’s not always clear why. It’s not always because of the number of classes per day. I think five classes a day could be manageable with other structures in place to support. As an example, tighter restrictions on class size, or prep time proportional to workload.

How it works here is that each district negotiates a maximum class size with their teachers’ union. 35 is the maximum number of students I can have per class, and all of my classes have at least 32 students. The upper limit in my last district was 36. PE classes have a higher limit, and special education classes have a lower threshold, but generally speaking, the limit for general ed classes is 35. And that’s huge.

Let me break down what this means for teachers’ schedules, and I’ll try not to use jargon. When I teach four different classes (like English 1, English 2, English 3…), those are four entirely different curriculums. That’s different from teaching the same curriculum four times in one day, because each of those classes requires different preparation. But most of the time, despite this, every teacher is given the same number of prep periods per day: one.

To give a more specific example: I co-teach two of my classes with a special education teacher, which means we have a cohort of students who have individual learning plans. To address those students’ needs, she and I need to co-plan. But I still only have that one prep period — to meet with her to co-plan those classes and then to plan for my other two without her. The amount of prep time a teacher is given during the workday doesn’t generally increase as our workload increases.

This structure also means that the newest teachers are often the least prepared, because seniority plays a role in how classes are assigned. So a new or young teacher, who likely needs the most preparation and support, will accept a large number of classes because they don’t have the job security to say no — and then they inherently will need to spend long nights and weekends prepping for that schedule, because the system isn’t designed to give them work hours to prepare. It takes a toll on people.

Both the blessing and curse of teaching is that it can be done in isolation. We all have our own individual classrooms that we sit in, and we do our own work, and there aren’t always natural opportunities for connection and collaboration.

That isolation can draw people away from the profession because you start to believe, ‘I’m the only one doing this work, and I’m all alone.’ That’s hard in any job, but particularly one that has so many implications for others’ lives, and it takes an emotional and mental toll. So I think finding ways to support teachers in building strong connections with one another is one of the most important things that could help boost morale and keep high-quality teachers in schools. We need to create and invest in a culture of collaboration between teaching staff.

I was once part of a survey with Teach Plus where we asked teachers, ‘If your district had $100 per teacher for self care, what would you want?’ And most teachers said they wanted coffee and food in the teachers’ lounge so teachers would be encouraged to gather there. They wanted to go to the teachers’ lounge and see each other, and they asked for more paid time to collaborate with one another. So it’s not just vacation time that people are asking for. We want time together, and teachers are asking for opportunities to connect and to be seen and to be heard, and I think that districts don’t take that seriously enough. I wish they did. Because when you feel really connected to people, you want to stay, and you have colleagues to lean on when you’re feeling overwhelmed.

I have seen the public perception of teachers shift dramatically over the past six years. When I became a teacher, there wasn’t a lot of support, but the general consensus was, ‘You do good work.’ And then the pandemic hit.

Now there’s a mixture of ‘teachers are heroes’ and ‘you’re not doing enough.’ So many people developed hate for teachers because their child suffered during the pandemic and they felt helpless. That was real for people.

In terms of the criticisms around what teachers are teaching, it goes back to what we talked about earlier: the national disconnect about the role of the teacher. As much as I think it’s valuable to know how to read and write and do basic mathematics, the reality is that young people spend the majority of their waking hours in school, not at home. They’re here eight hours a day for most of the year, and that means that we have a big impact on the type of people they become. And if you look at the mission statements of most schools, they say something along the lines of ‘helping young people become good citizens of the world’ — universally, schools have that mission. But when it comes down to it, most people don’t know what that means.

When I think about helping young people navigate the world outside of school, I think about things like, ‘Can you talk to people who are different from you, who have different beliefs from you? Do you know how to navigate understanding political concepts, so you can choose how to vote when you leave? Do you know how to make good financial decisions?’

Imagine if every kid could leave high school feeling ready to navigate the world. That should be the point, right? To prepare students for whatever comes next? But it’s not always part of our job description.

We know that kids spend a lot of time in school, but we can’t accept the level of responsibility that attributes to teachers. And I want people to do that. I want us to trust that the educators who are in these roles are doing the things that we’re doing with fidelity — and out of love.

When you think about a kindergarten classroom, you generally think about high-energy kids playing and talking to each other. You wouldn’t expect half of the class to be dead quiet, right? Because they’re children. They’re imaginative and playful. But somewhere along the trajectory of getting to high school, that fizzles out in a lot of kids.

In elementary school, we tell kids, ‘Sit down, be quiet, don’t do that, stay where you are.’ And then they get to high school, and we say, ‘Why isn’t anybody talking? Get up out of your seat.’ So there’s a push and pull of the norms that we set for students.

At the start of each year, most teens are very quiet, and they’re not wanting to share and not confident in their work. They’re not willing to take risks. And so I love the second semester, because by then you’ve built a relationship with all of your students, and you know them really well. You have an idea of how to tap into what they each need individually to step up into themselves. It’s empowering for me to see students volunteer to share something in class — or to see the moment when something clicks for a student and they say, ‘Oh my gosh, I do understand how to do that. I didn’t need to ask for help this time.’

Even today, just before you got here, I was with a student who’d been having a tough time. He didn’t connect well with the teacher in his last English class. He got distracted a lot, and he barely passed. In my class, he asks for help a lot now. He’s getting it done. And today, I gave him an essay back and told him, ‘You did really great on it.’ He has an A in the class, and it’s the first time he’s ever had an A in English, and he lit up today while looking at his work.

Those moments are what keep me coming back every day. As teachers, we come back to see students’ confidence grow. And I feel lucky to get to do this work with teenagers, because it’s really special to see these people who are almost adults stepping into what has always inherently been in them, but they haven’t really been able to reach.

–Jenna Hewitt King

English & EL Teacher at San Leandro High School

San Leandro, California