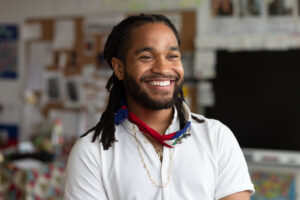

I pretty much always knew I wanted to work with kids because I always found joy in it. I felt I had innate instincts, and I knew how to navigate different situations.

When I was seven or eight years old, I remember being a caretaker for some of the toddlers at my synagogue. I was their ‘babysitter.’ There was something so special about their excitement to see me — that recognition and feeling of being valued. I felt the same as a reading buddy in elementary school, having younger students to read to.

After graduating college, I originally planned to be a wilderness therapy guide for kids, but I wasn’t comfortable waiting so long for the hiking interview date, so I took a job working as a second grade teacher at Feynman School in Maryland. I felt like my strengths were able to come out: problem solving, project management, planning and organizing, but also being creative and having fun with the unplanned or unexpected. I just found myself loving it.

My first year teaching, my co-teacher was often out for personal reasons. I was left to figure it out. When we finally reached the end of the year, I had families and students telling me about how much they learned and how much they loved our time together. It was really special. It felt like I was enough to those who mattered.

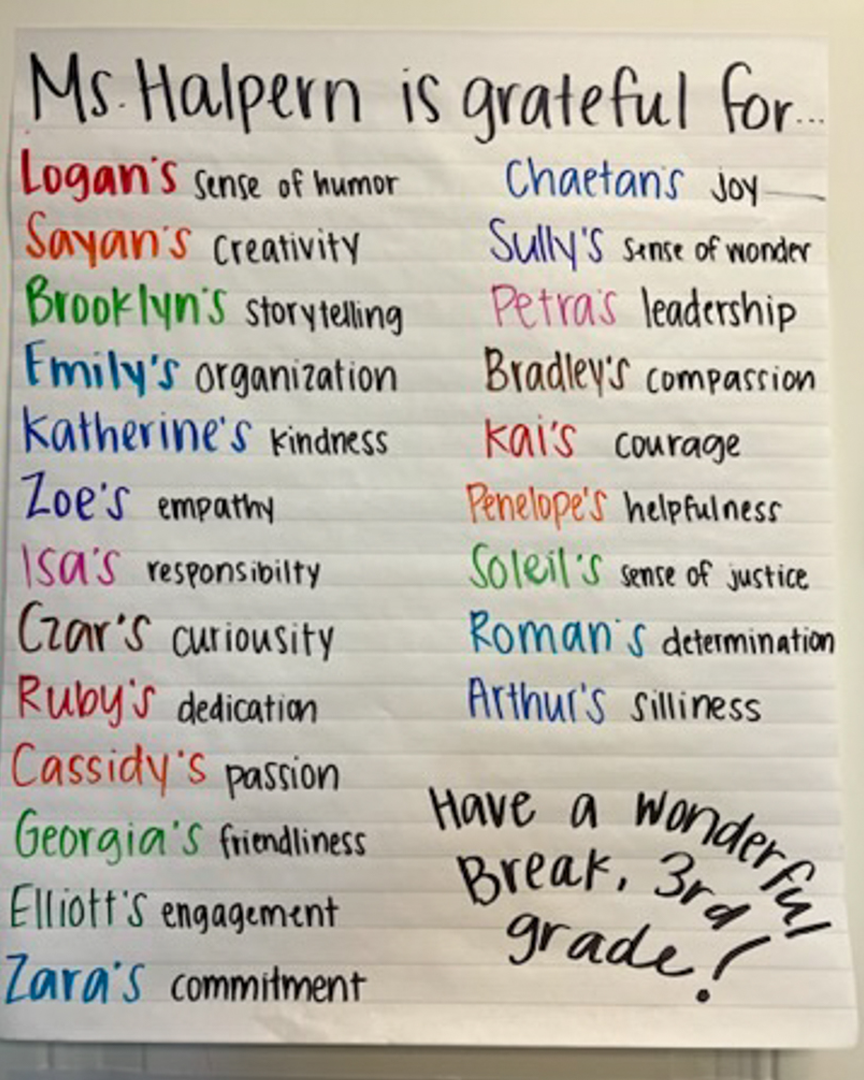

I loved the chance to say to the students, ‘I love so many things about each of you, in your own unique ways.’ I think I always found purpose and power in learning from and with young people even if I didn’t have the words to name it. I only recently figured that out about myself.

I knew I wanted to eventually move out of private schools simply because I believe in the public school system. I was a proponent and wanted to be there, but I didn’t have a teaching certificate. I ended up doing an online teacher prep program while I was at the private school; I got that certification with the intention of moving to public school.

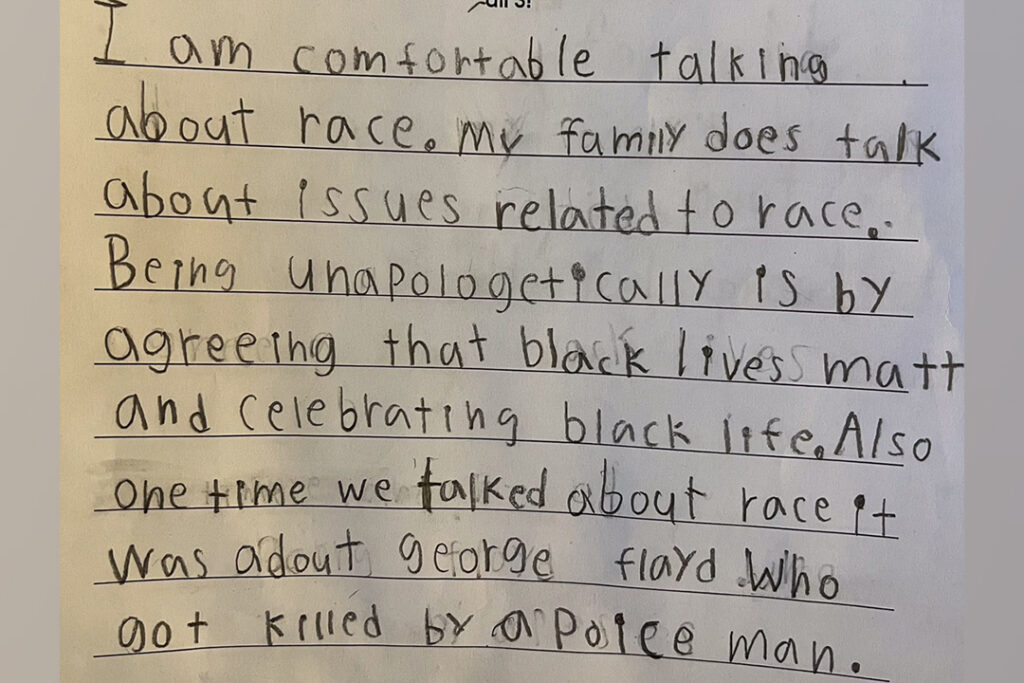

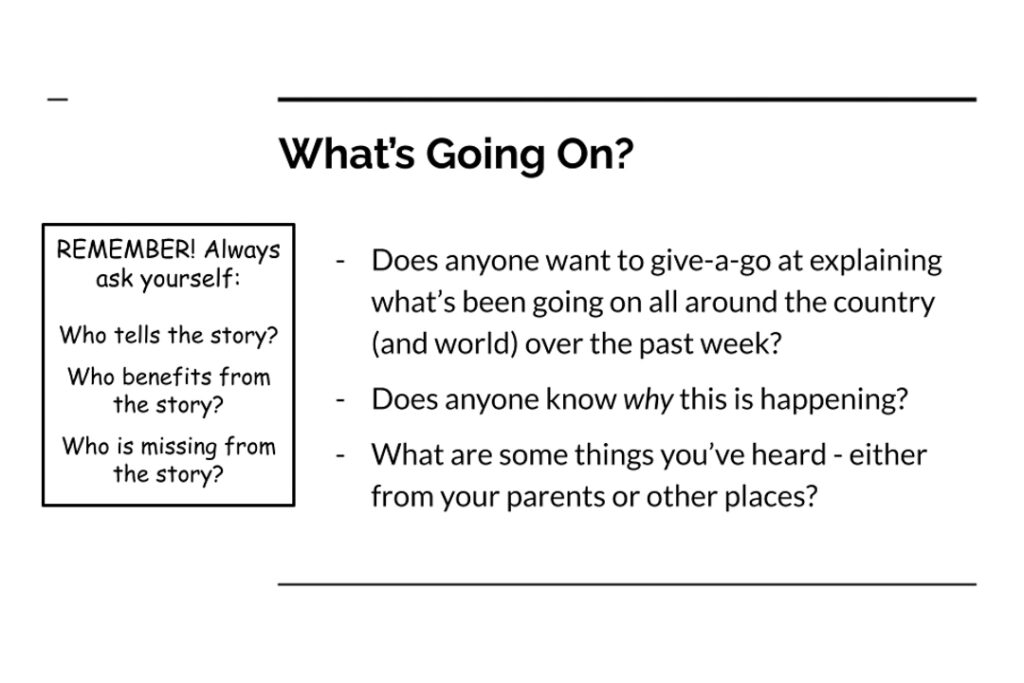

At the private school, when the pandemic hit and there were Black Lives Matter uprisings, I did a mini-unit on the history of policing. I had done a full unit on colonization with my students, so we were able to tie current events back to colonization and talk about how systems of power are interconnected. It was great. I thought I’d be able to bring those same lessons and ideas to my next school, but it didn’t fit in with the public school social studies curriculum.

Once I moved to public school, during the pandemic, another teacher showed up to one of my Zoom classes, unannounced, and watched the very same lesson I led on the history of policing that my previous third graders — and their families — were so appreciative of. This teacher went to my supervisor and said that what I was teaching was problematic. That’s a moment when I really felt the bureaucracy and missed the privileges of private school. In public education, it’s so hard to do what you think is right for the students and push against the norm.

As a kid, my dad used to say, ‘Change only happens by going against the grain.’ He used to tell me that it’s an extremely isolating experience, to stand up for what you believe is just. He was right.

I have two pieces of artwork here: one says ‘Another World is Possible’ and the other says ‘Plant the Seeds of Peace With Justice.’ The idea is that creating a better world inherently sits within tough conversations. Teaching students about justice requires them to know, feel, and sit with being angry or upset. It also requires them to tap in to joy, love, and care for one another. Only then can we build a world of peace.

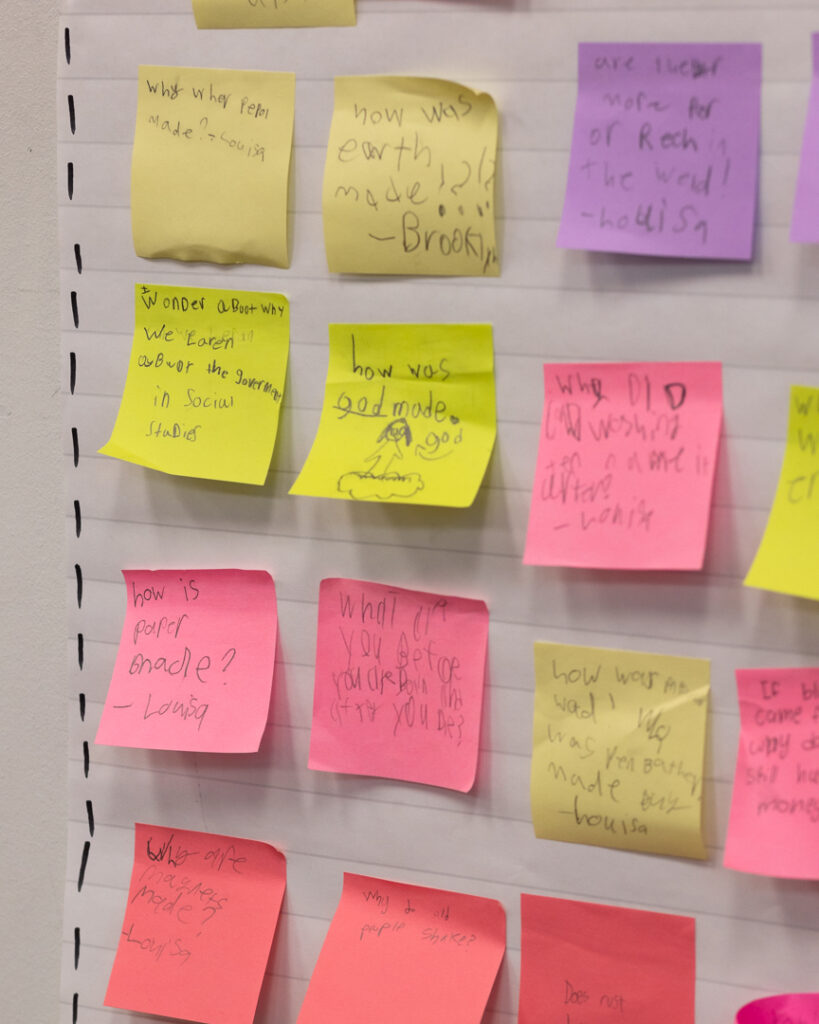

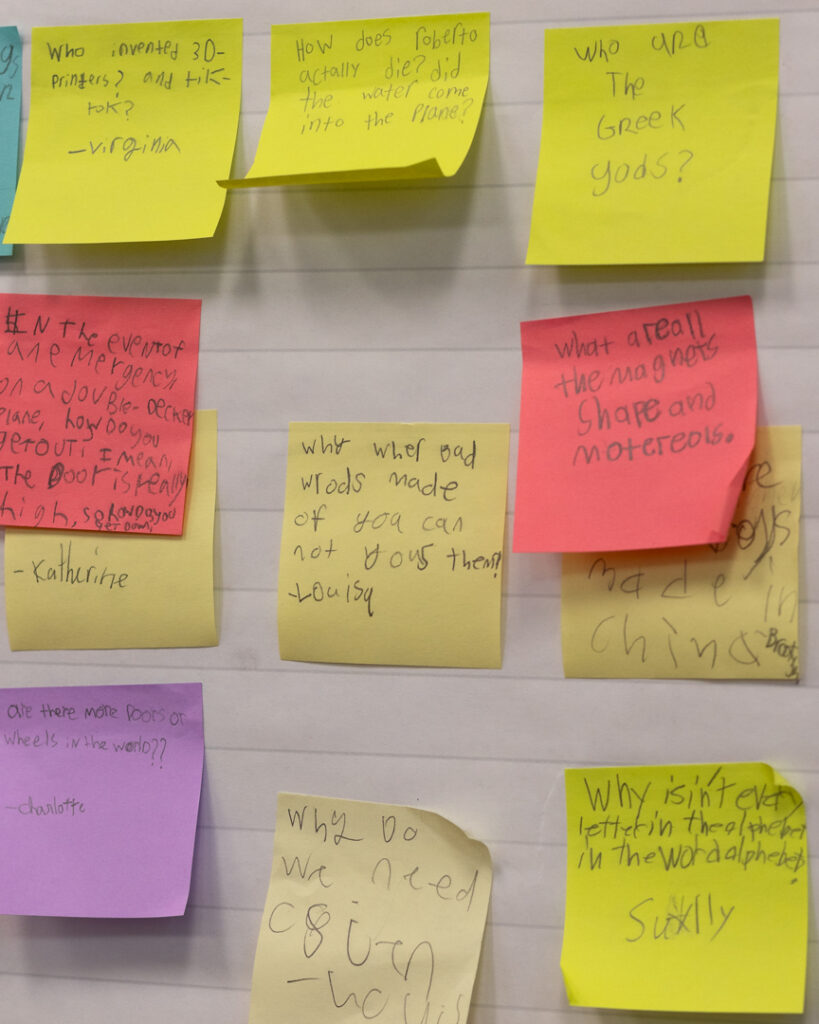

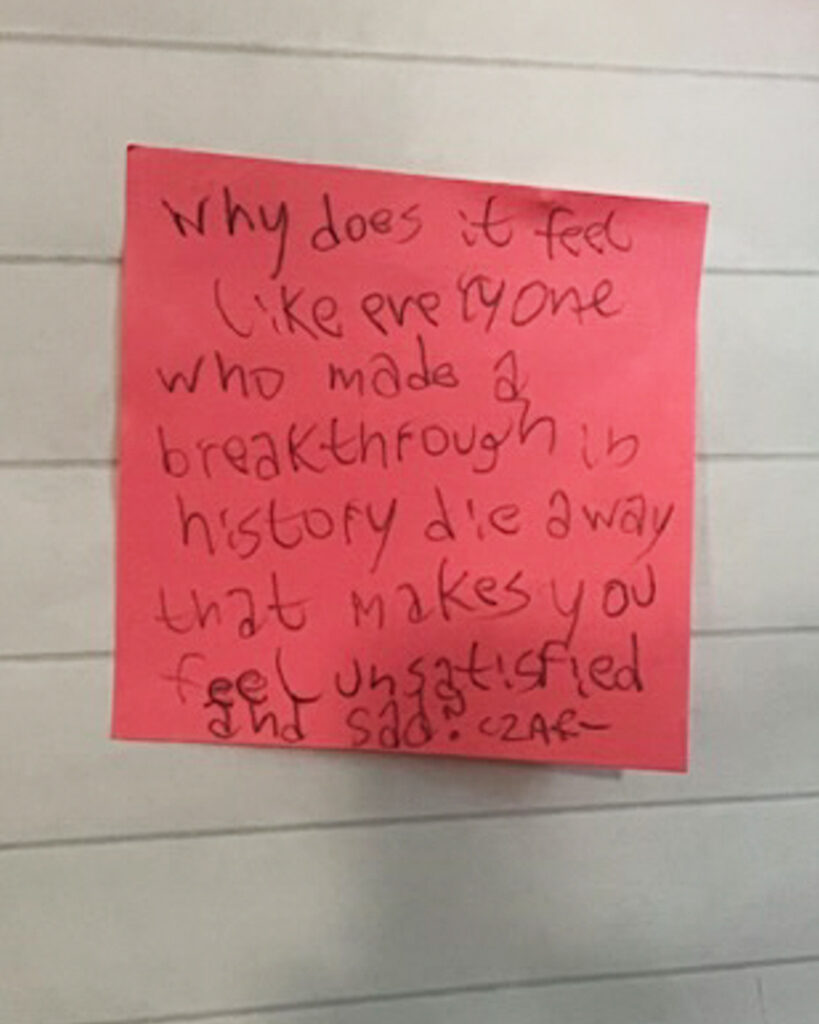

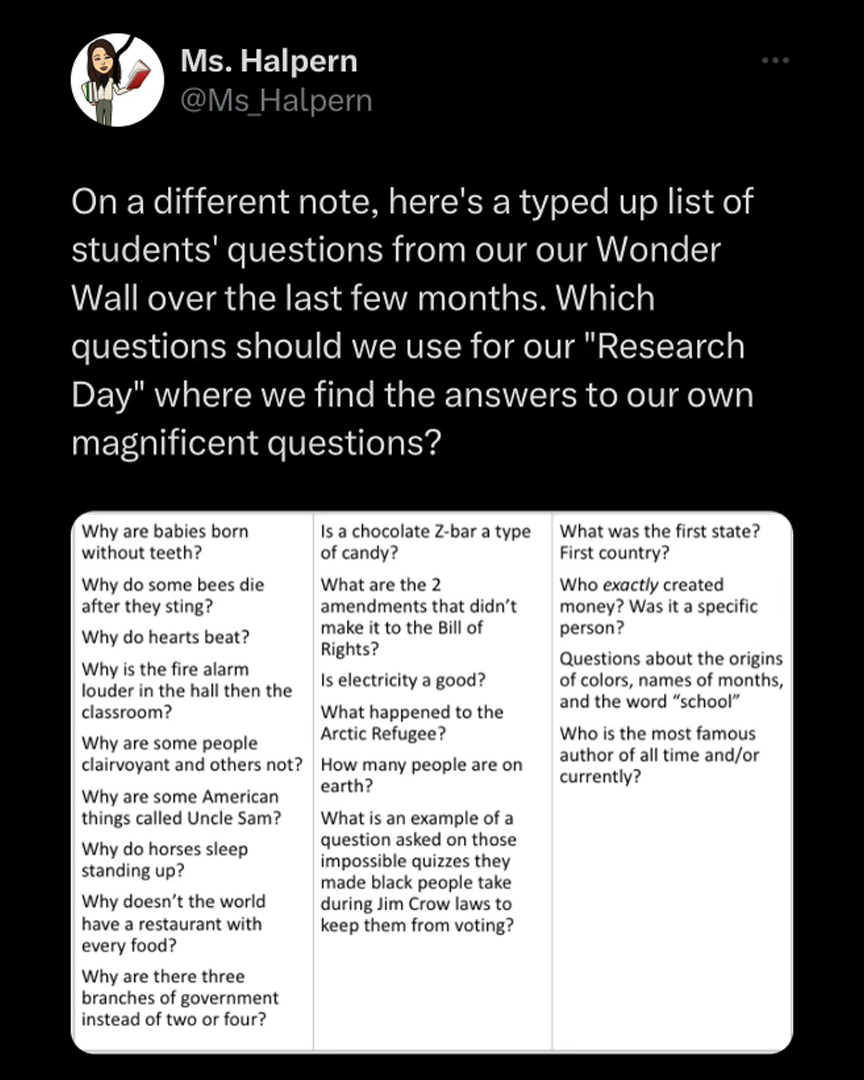

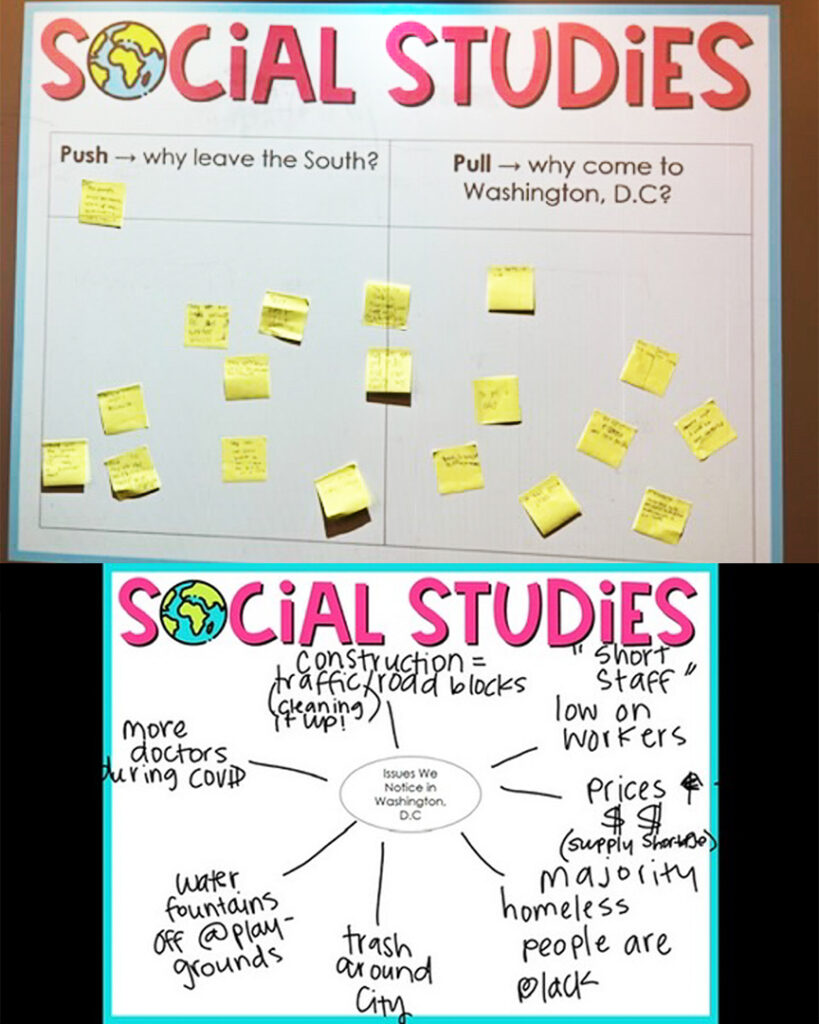

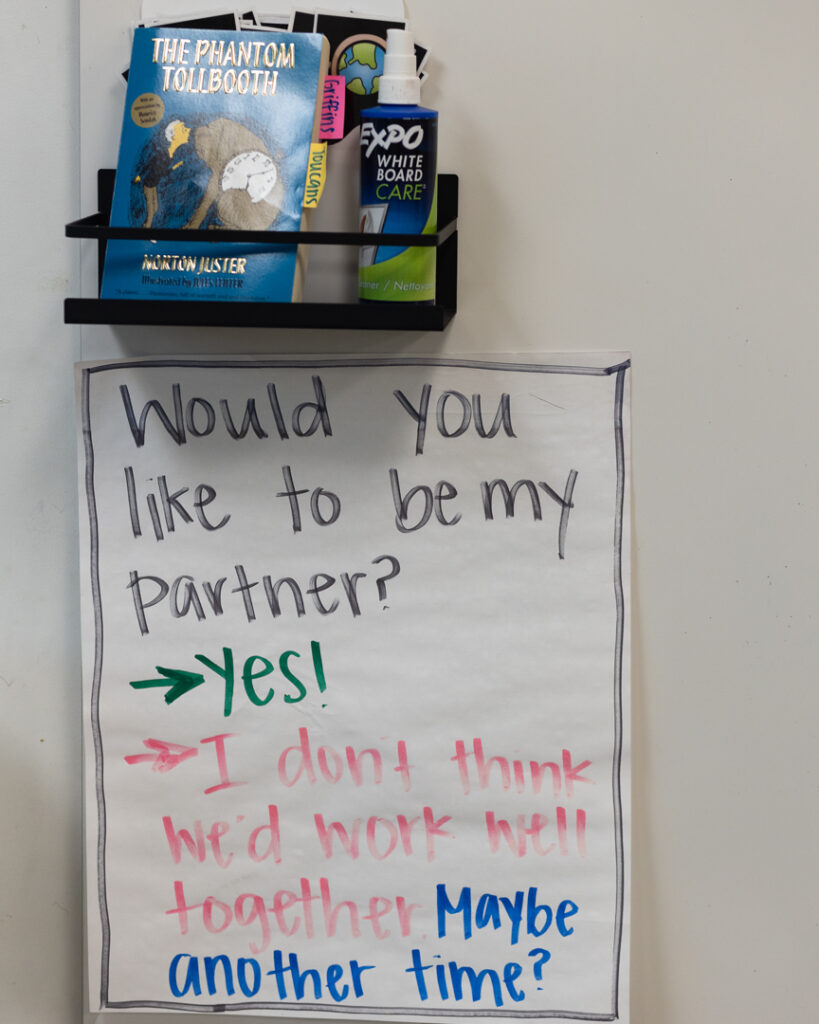

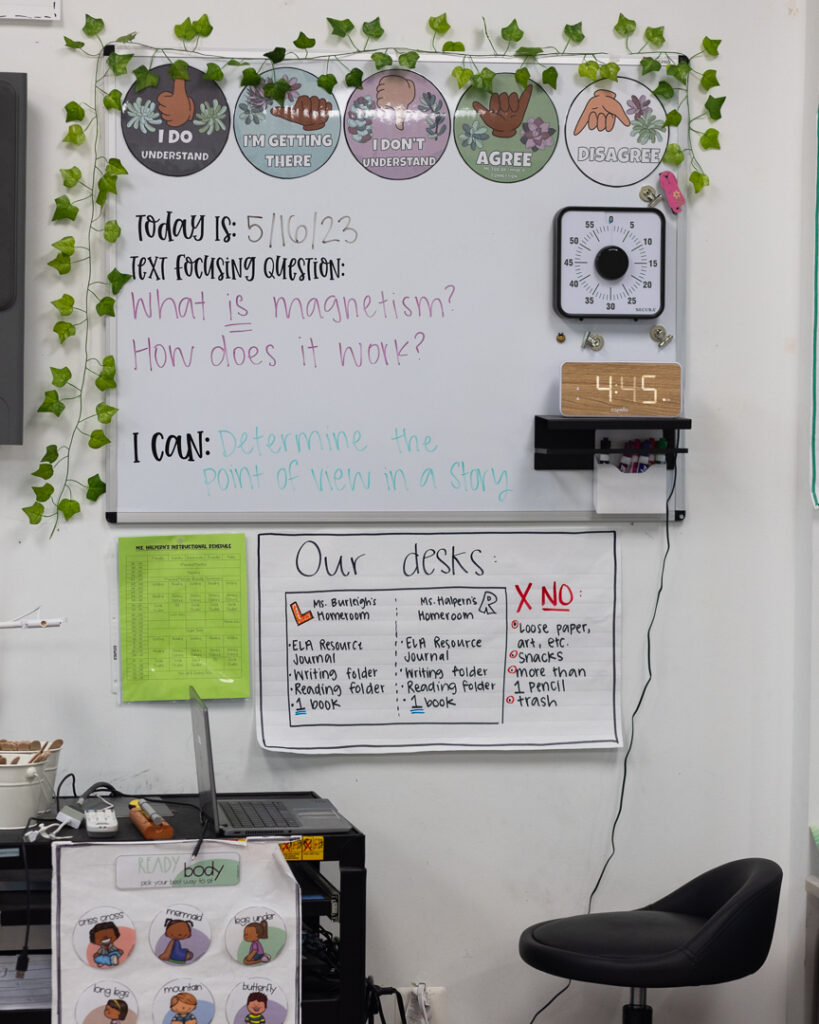

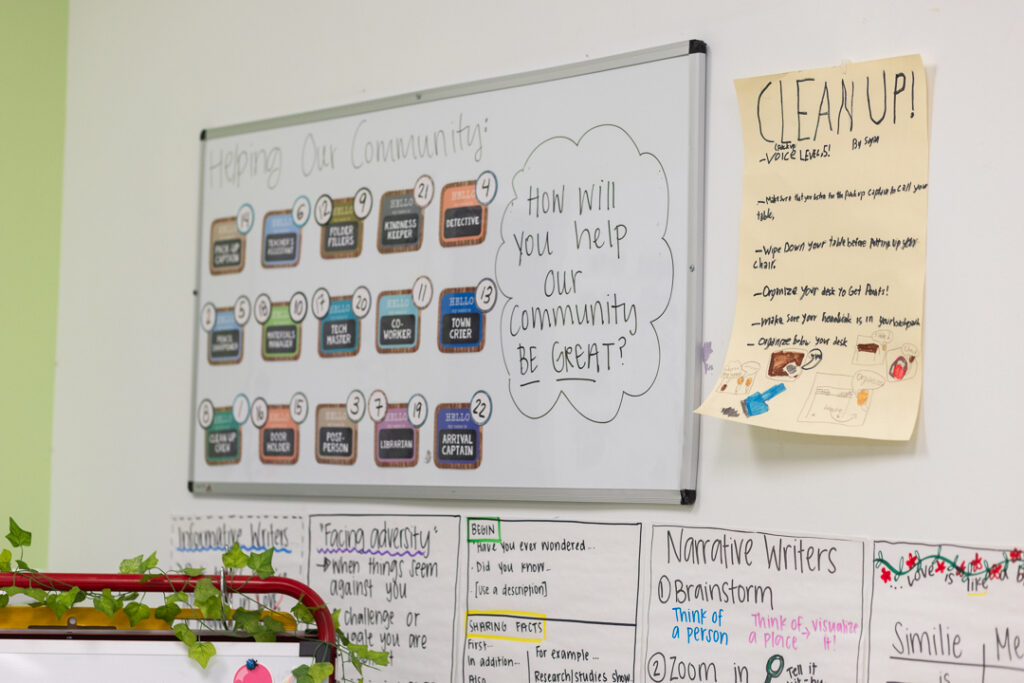

As a teacher, it’s so important to build a space to ask and answer questions about the way the world works, how the world has worked in the past, and how the world could look in the future. I have students place any questions they have about the world on the Wonder Wall throughout the school year. Then, every few months, we have a Research Day, where we come back to their post-it note questions. They’re great questions: ‘Why aren’t babies born with teeth? Who came up with the color purple? Why does racism exist?’ Some of the questions have answers, and others are simply there to ponder and learn more.

I provide all the possible resources I can find to help them answer their own questions, dig deeper into new ideas, and come to their own thoughtful responses or opinions about whatever they’re wondering about. Students then present their findings to the class since we’re ALL teachers and we’re ALL learners. The core purpose of school is to have the courage to ask questions and have the courage to find out the answer.

Children are inherently brave and courageous in their curiosity, imagining, and reimagining. They are just themselves. That’s beautiful. There’s something to learn from that.

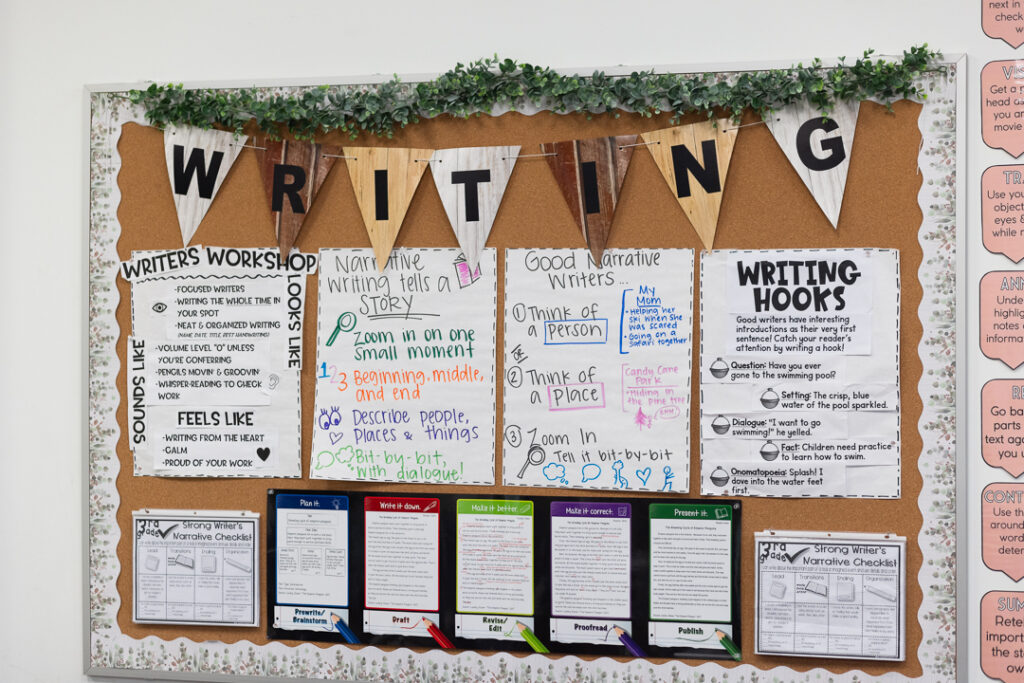

Third grade is great because they’ve just taken the leap from lower elementary to upper elementary. They’re starting to write more and are expected to be more independent. It’s a big adjustment at first. But then all of a sudden, it all comes together. They start to believe in themselves, and as a teacher you can tell them, ‘You got this, you can do this.’

It’s like this little halfway point where you’re not a tween, you’re not a little kid, you’re right there: you’re ready to go. Many still like school and are excited to learn, explore, and find meaning all around them.

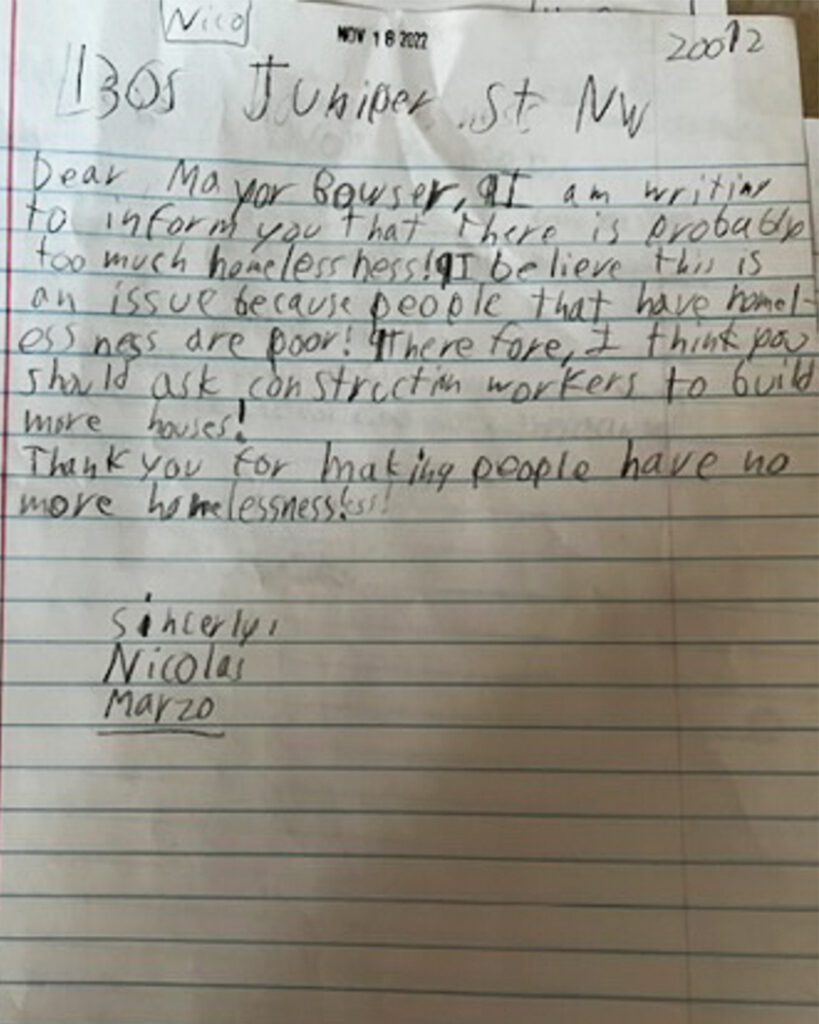

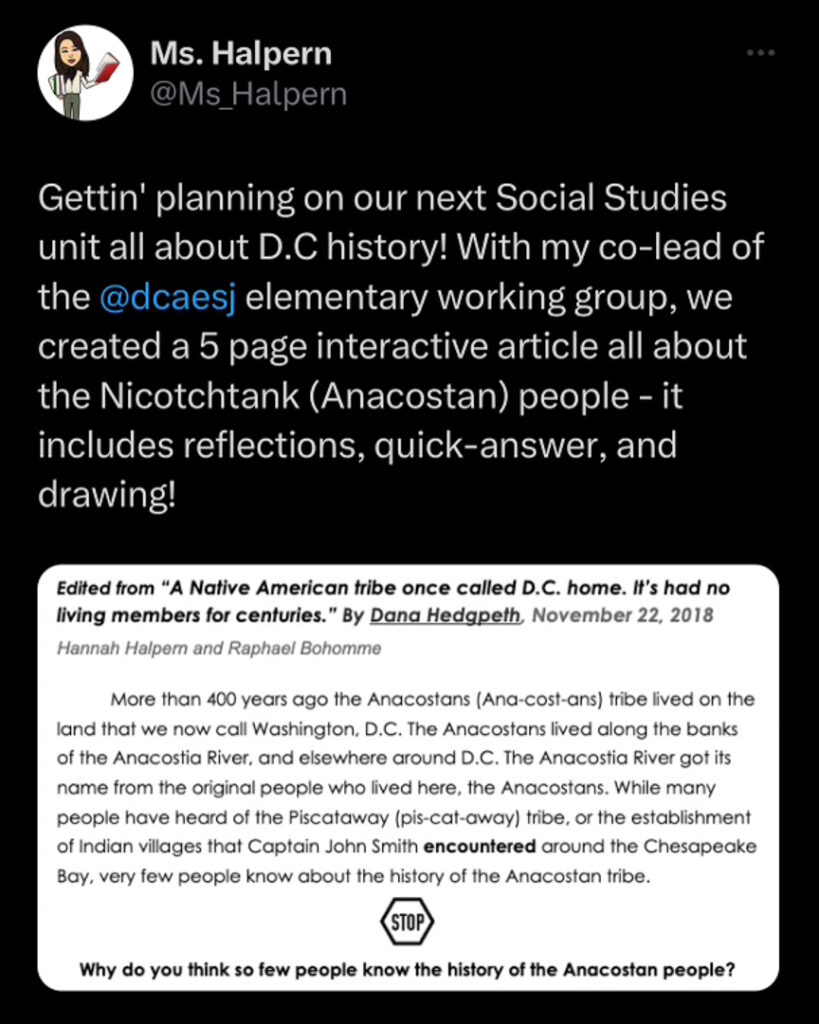

Third grade social studies is focused on DC history. I bring in all sorts of resources and questions to tackle a complicated history of the district. All kinds of questions come up: ‘Who are the Nacotchtank people, and why is there such little record of the first peoples of this land? What is gentrification and how does it work? How does moving in or being pushed out impact a culture?’

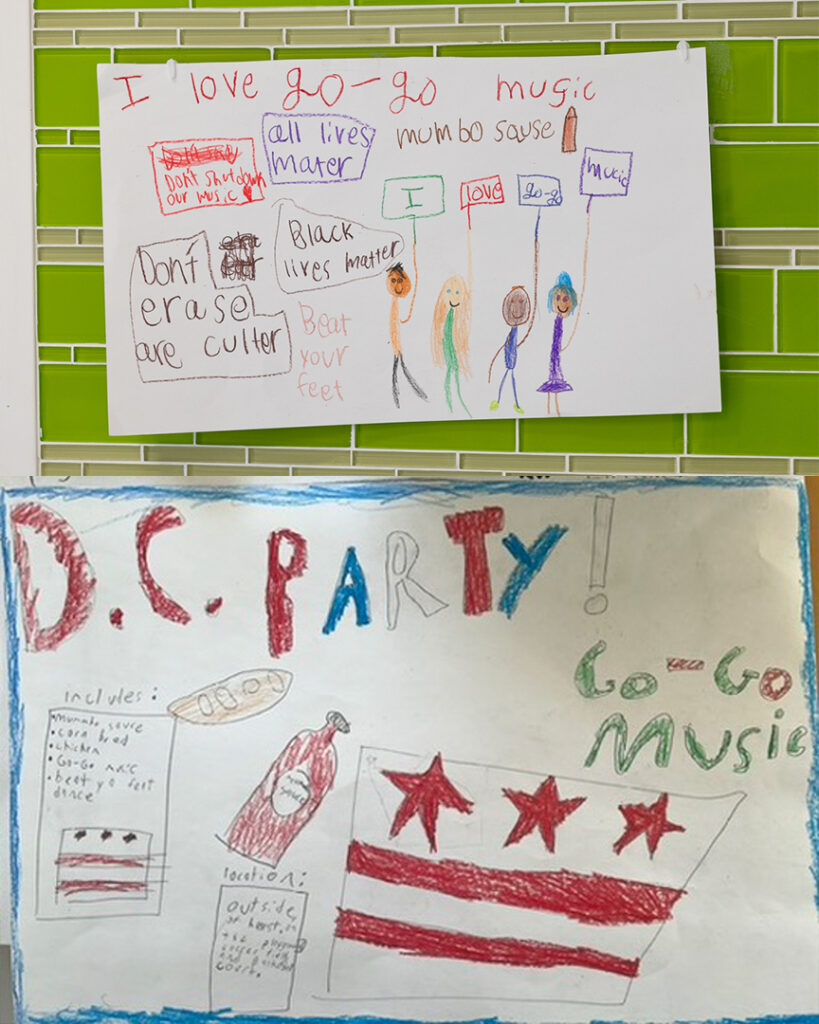

We had what we called our DC Party, which was the students’ idea. They created these posters that really showed me their understanding of what we had discussed. They claimed a lot of DC culture as theirs in this beautiful way. We talked a lot about how you honor a culture. How do you make sure a culture doesn’t get erased or left behind? Whose cultures are more likely to be left behind or purposefully erased and why?

Students were so engulfed in our learning of gentrification that some of our students, whose family members are architects, became concerned: ‘If my family builds buildings in the city, is that taking away from other people’s homes? Is that one of the reasons why things are becoming more expensive?’ As a collective, we talked through how there are pros and cons to development — an individual building is not the same as a need to change a greater system. This brought us back to our learning of both local and national government and how we can implement real change.

That’s one thing I love about third graders in general: their sense of social justice. You can provide them with the information and they’re ready to question the status quo and imagine a better world.

I’m in this collective, DC Area Educators for Social Justice, that’s made up of educators from all different backgrounds, working in a variety of school settings, who come together to create actively anti-racist curriculum and to be in community with one another.

I go to that group with problems I’m facing, fun ideas I have — anything related to kids, pedagogy, and local or national education issues. We’ve merged the upper elementary and middle and high school meetings to try to build up momentum. But it’s hard. Teachers are tired, and they don’t want to go create and plan for brand new lessons on a Saturday afternoon and I don’t blame them. In trying to build momentum and organizing power within DCAESJ, I try to remind myself that since the pandemic, people have been burnt to a crisp. Everybody is running on very little time and energy as it is. Thinking and implementing ways to dismantle educational systems that are hurting our young people is a very tall task for those who are already extraordinarily overworked and ill-treated. I joined Hearst Elementary School virtually in 2020, which made community-building difficult, so DCAESJ was crucial for me to find like-minded educators as both colleagues and friends.

Sure, I have days where I feel frustrated in the classroom. But I think I’ve had three times in my five years of teaching where I went home still frustrated by an interaction with a young person. I usually forget about it within two minutes of the time it happened. That’s how much I love teaching — I find it very easy to love parts of every single student… I’ve never had a student where I felt like I didn’t know what was going on, or where I’ve had difficulty navigating moments of joy with them. I just don’t have that experience.

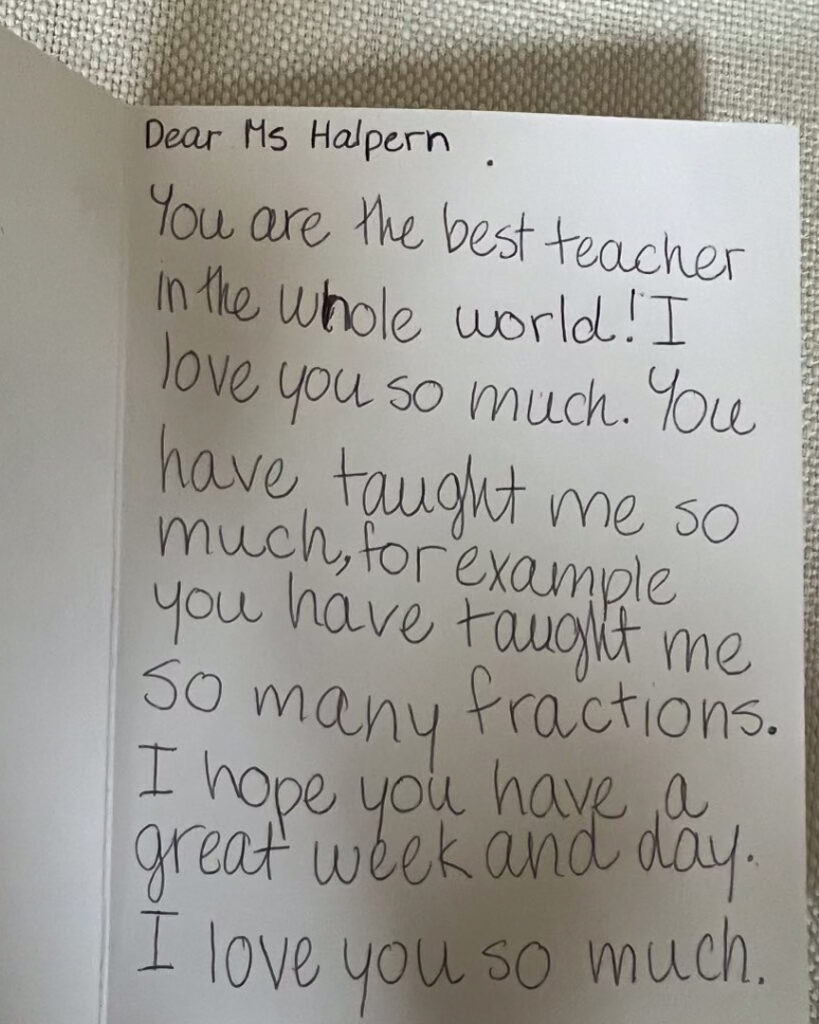

It is not a cute little Hallmark card. But I really do love every single person I’ve ever taught.

Many people have a general understanding that teachers work hard and don’t get paid enough. I think what maybe isn’t necessarily thought of is how much time and energy is spent on the internal aspect of teaching. It’s not just grading after I leave work. I’m wondering what I should do next. I’m wondering how I can be better. I’m wondering if I should create this whole other new activity that I just thought of, that’ll take me several days to complete, but I think they’ll find it really fun. There’s no time in the schedule.

In some ways, I know it would be easier to follow a curriculum to a T, but that’s hard when many textbooks were written so long ago. They were written with a particular winner of the story in mind, with a particular bias and understanding of how the world should work.

DCPS recently implemented a math unit on finances for third graders. On the one hand, I can see a benefit to certain learning skills like saving money. On the other hand, what would it look like to not have students feel that their one purpose is to have a job and make money to survive? How are we preparing kids for the reality of the world while simultaneously supporting them in reimagining, and creating, a better reality for all?

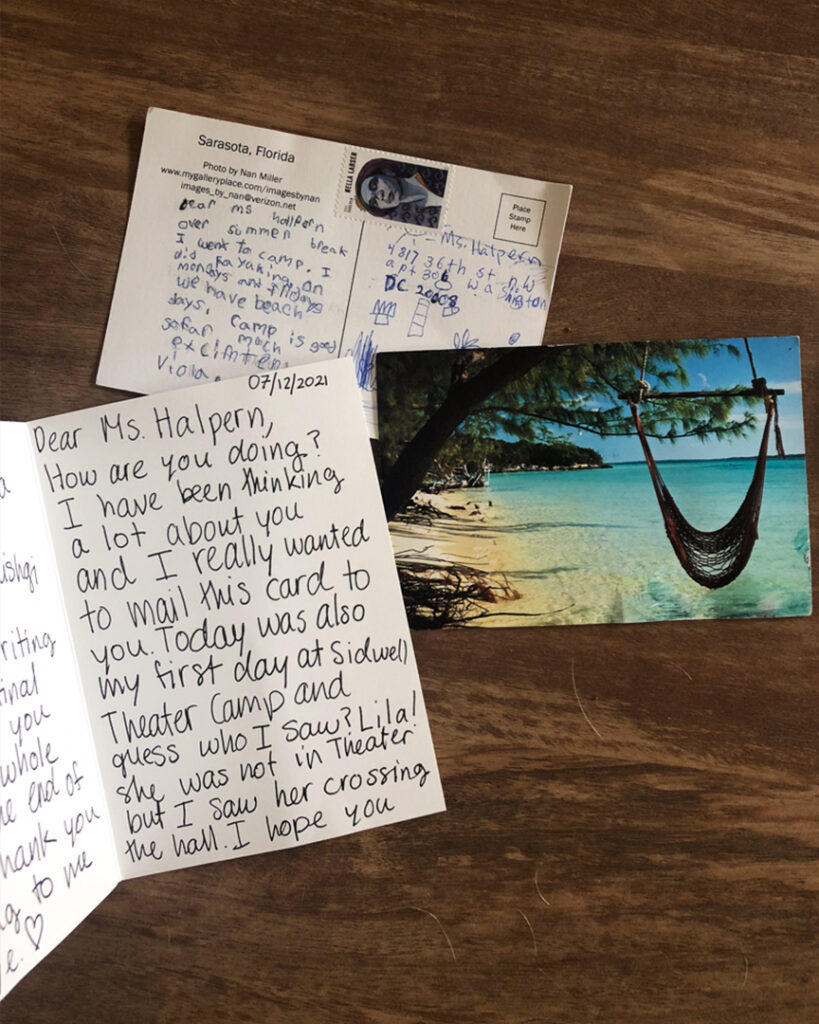

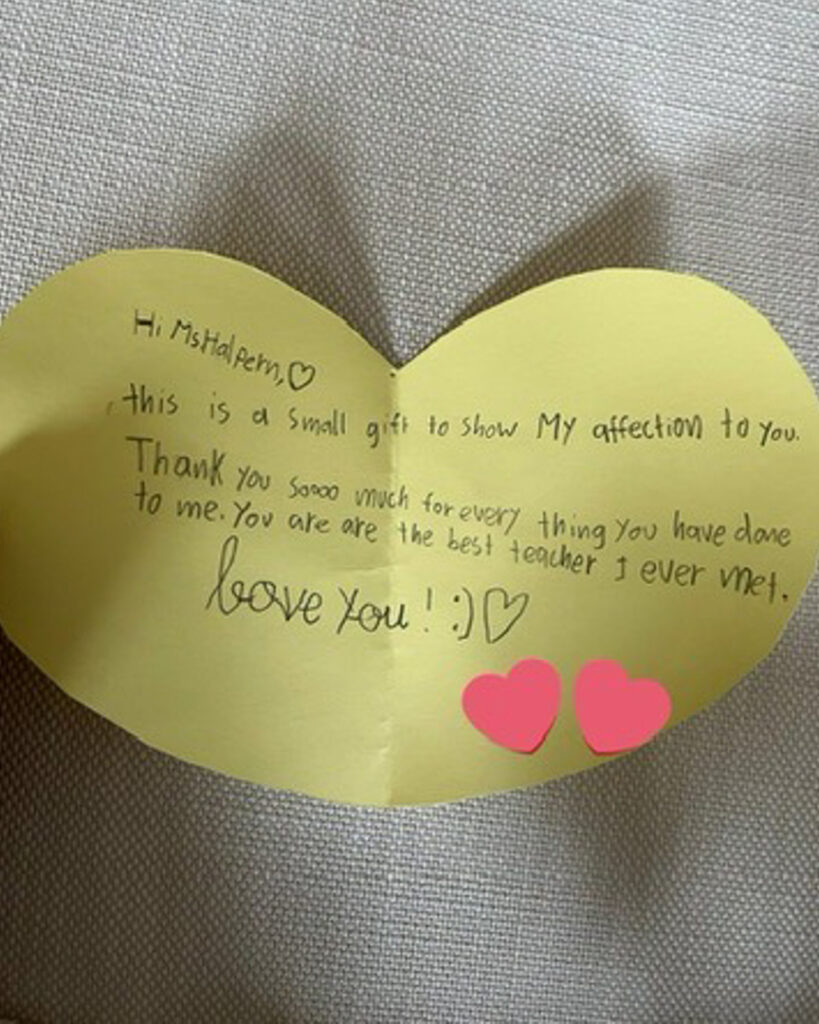

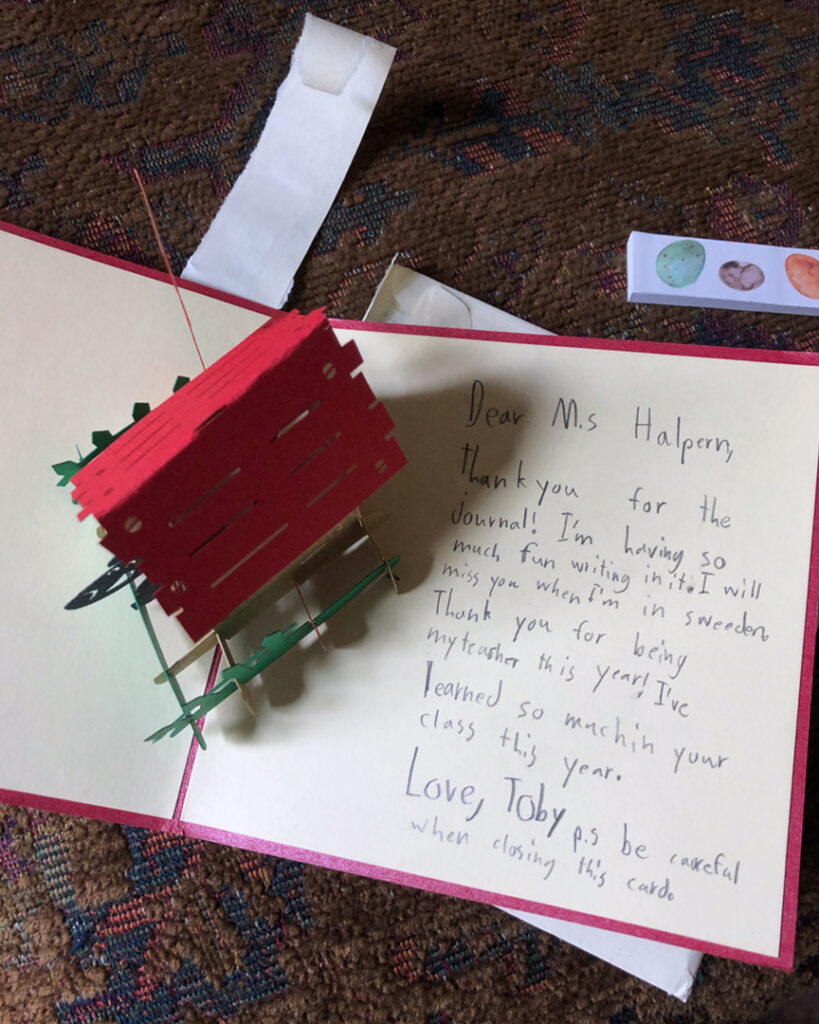

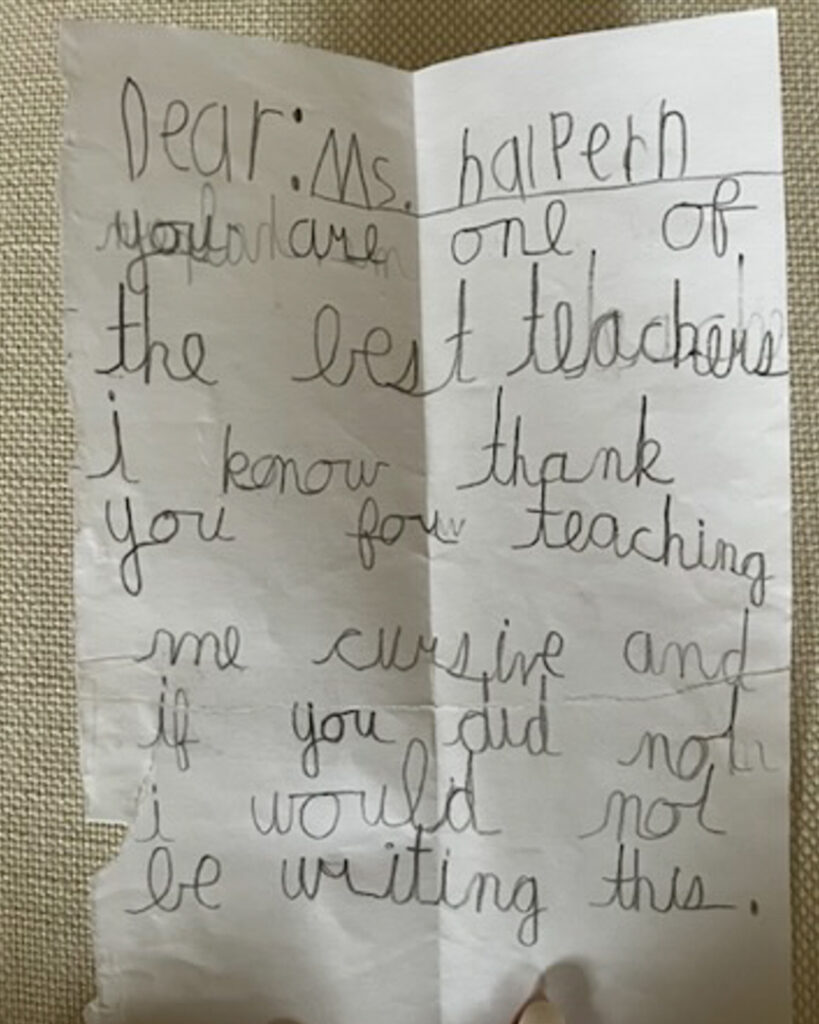

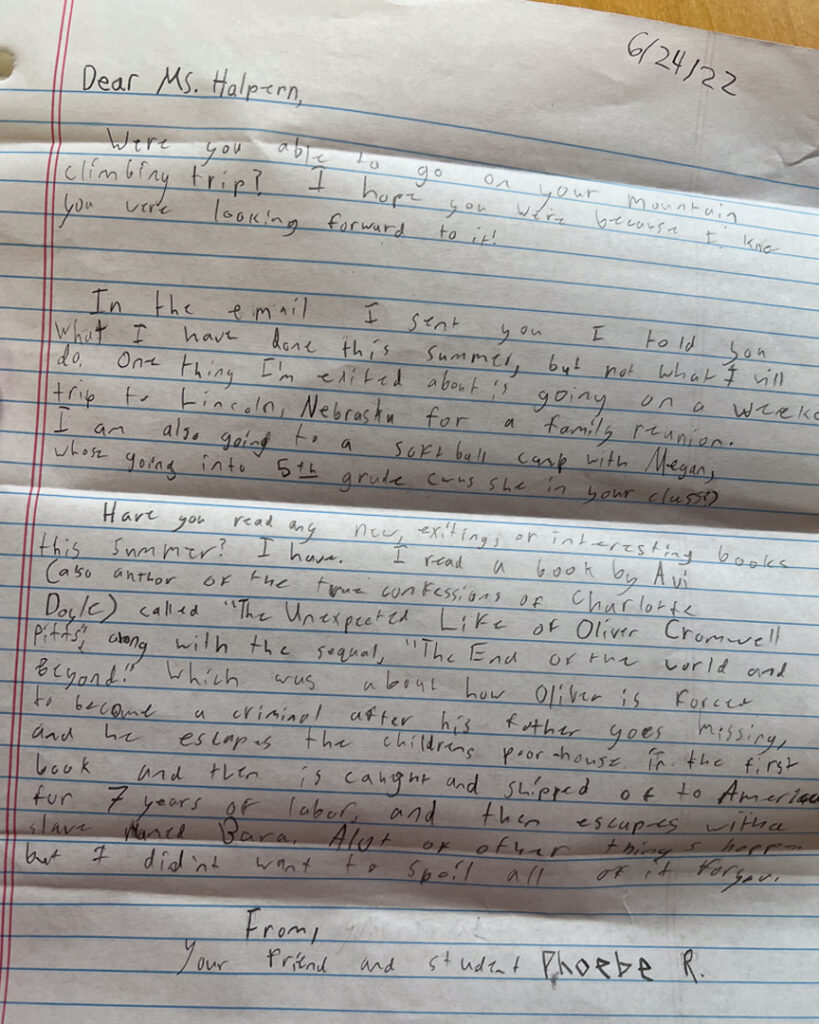

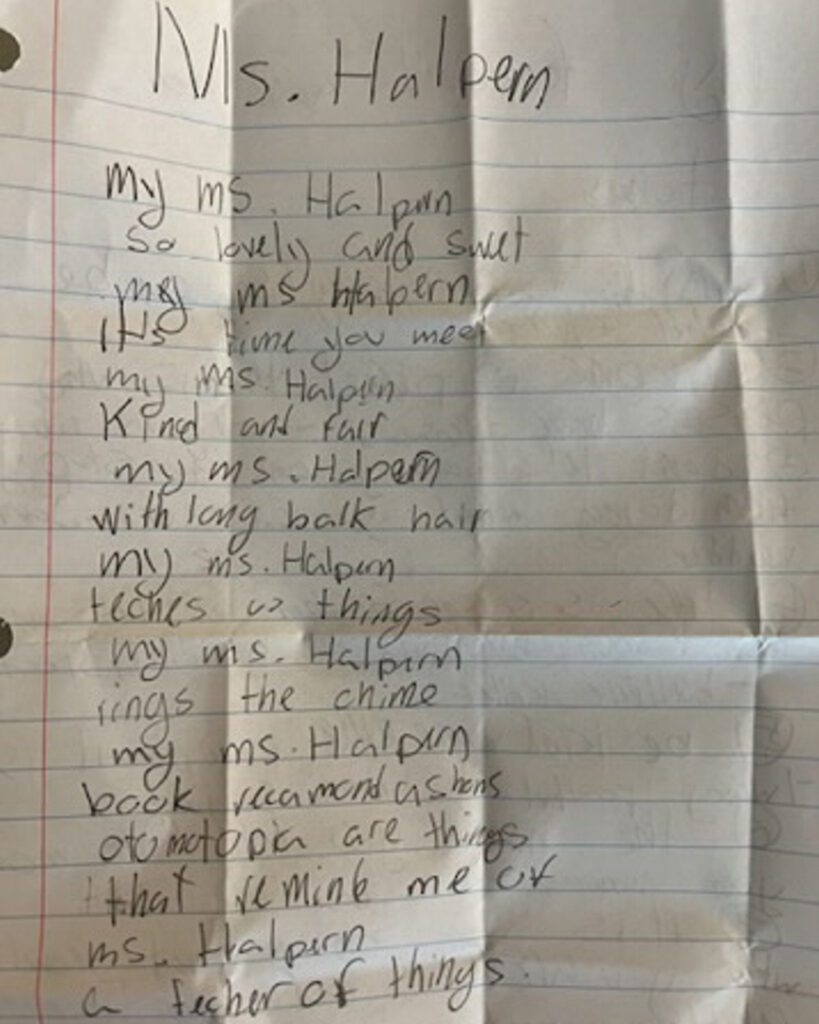

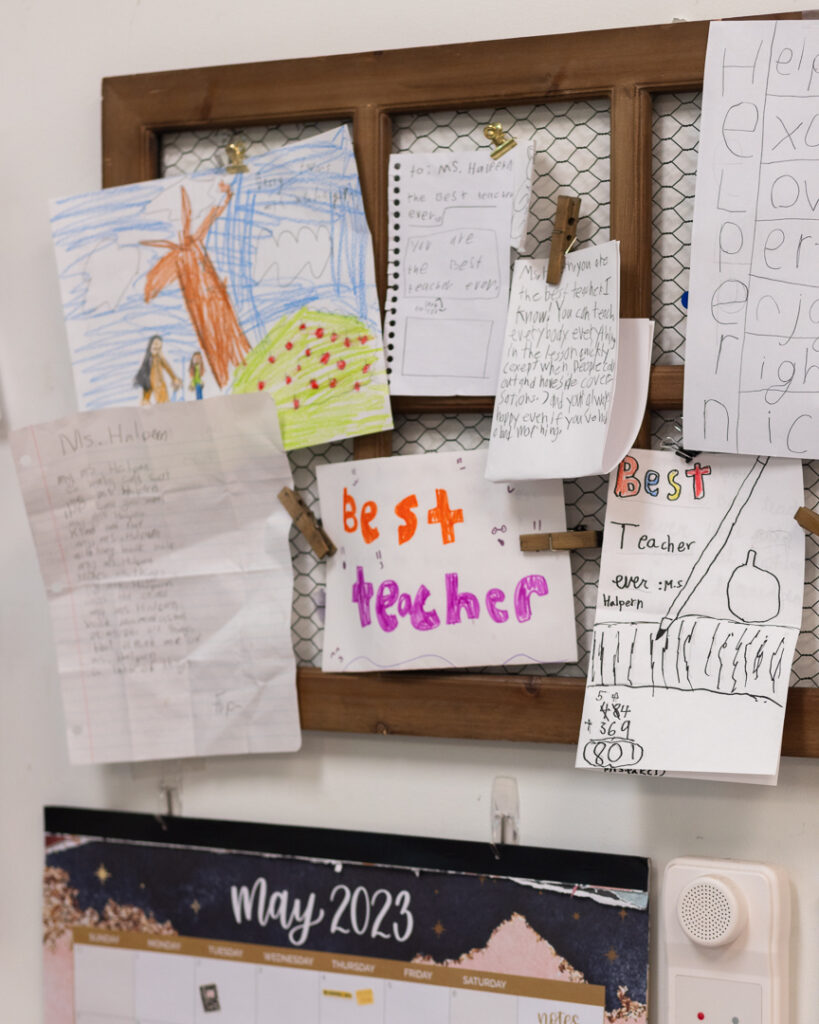

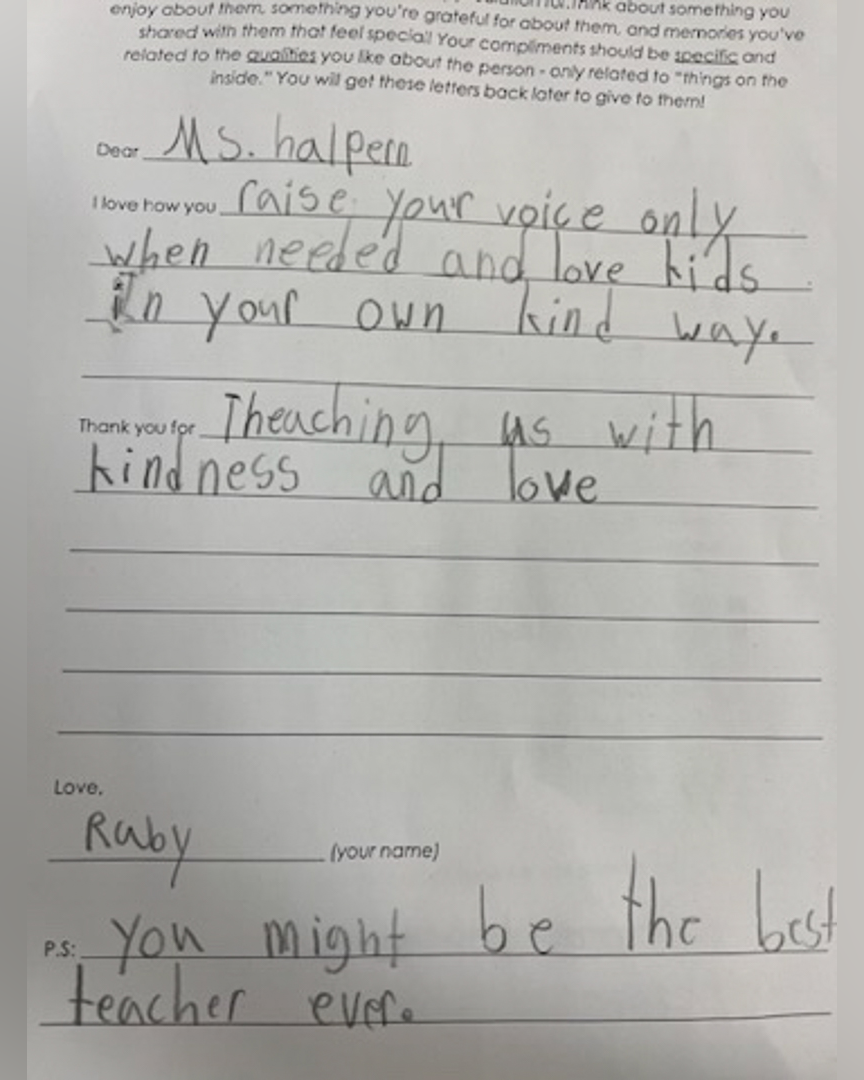

One of the only things that softens the blow is receiving thoughtful words, from admin, co-teachers, students, and their parents: ‘I see you and I appreciate you.’ I’m good for several weeks if I hear that. That’s my fuel.

When someone takes time to think about (and then shows you) that they see you and respect and care about who you are and what you do — those words of affirmation make a bigger difference than some people might think.

Connection through communication means a lot to me. I even penpal with my students over the summer, and write them handwritten notes throughout the year, just to let them know: I see you, I care about you, I’m here.

It’s a real statistic that a lot of teachers leave DC Public Schools because of the IMPACT score. They may be forced out because of IMPACT, or maybe they just hate IMPACT so much that they’ve left. But getting a poor IMPACT score does not equal being a bad teacher.

I’ve had several years of ‘highly effective’ IMPACT scores, but then the moment it switches who’s scoring you, all of a sudden you realize it’s a subjective understanding of who you are and your capabilities. This year’s IMPACT was especially brutal on me in a way that I had not experienced. I felt targeted.

They’ve attempted to reform IMPACT several times, but it’s still awful. It is not an accurate depiction of a teacher’s methodology, pedagogy, ability to engage their students, passion, commitment, dedication… you can have all of those things and be told you’re an ineffective teacher.

It’s a 30-minute observation twice a year. That’s it. I have not seen them in my room, except for those two 30-minute blocks. So they don’t know who I am day-to-day as a teacher. They see what they want to see.

I had an interview with someone not that long ago who asked me, ‘What do you look for in a supervisor?’ When I answered, he was able to recognize it in a way that I didn’t at first: what I really need is to be seen for who I am as a person, and what I bring to the table.

If you only come into my classroom twice throughout the school year, how can you understand my ‘effectiveness’ as a teacher? You don’t know me, my teaching style, my students, what we’ve been working on over time… How can you grade an occupation so rooted in relationship and connection while simultaneously not seeking a relationship or connection with your supervisee?

I feel that if you don’t put in the effort to see who someone is, then you can’t possibly know them as a teacher, because teaching is so innately giving a part of yourself to a group of people. If you’re someone else, stepping into that space for only a moment, how can you possibly understand? And if the kids feel that they’ve learned so much, then what is left to evaluate?

With IMPACT, you’re evaluated on how you manage your time. For example, I asked my students to turn and talk about why they think spelling, punctuation, and capitalization were included in the rubric. I asked them, ‘Why do you think this matters?’ They spent seven minutes talking about the possibilities. I was told in my evaluation that I could have saved time by just saying, ‘Spelling, punctuation, and capitalization matter.’ Points were taken off on ‘skillful design and skillful facilitation.’ The evaluator rated me as ‘developing’ instead of effective or highly effective, because that person saw the children’s conversation as a waste of time.

I feel like this is in direct opposition to what I always tell my students: Be a learner, not a finisher. I want them to ask WHY and I want them to learn WHY. To me, that’s what school is about.

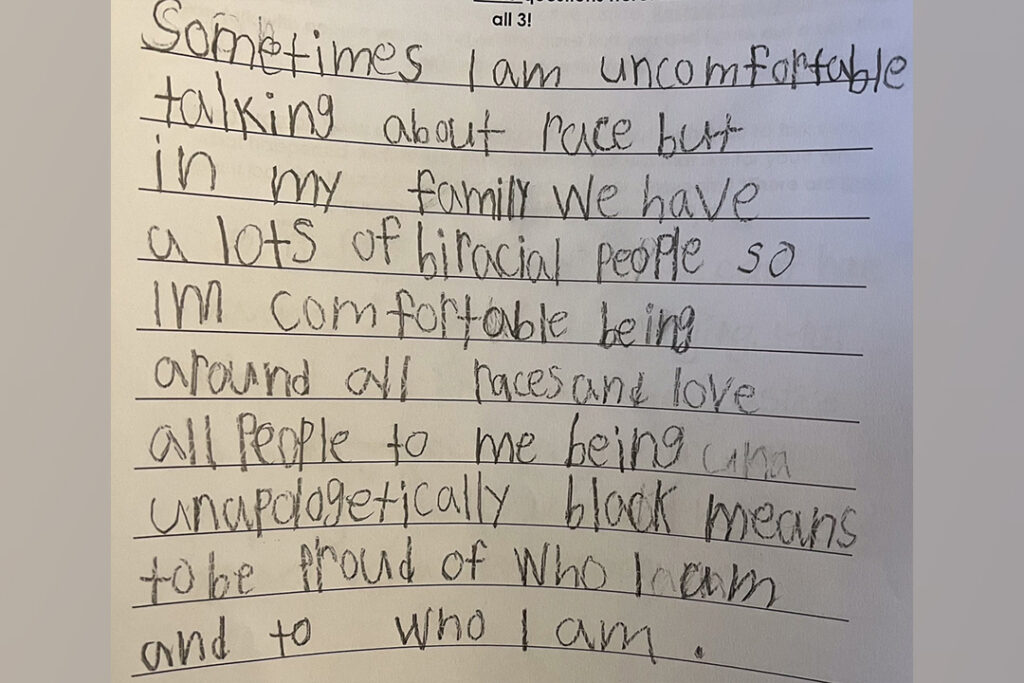

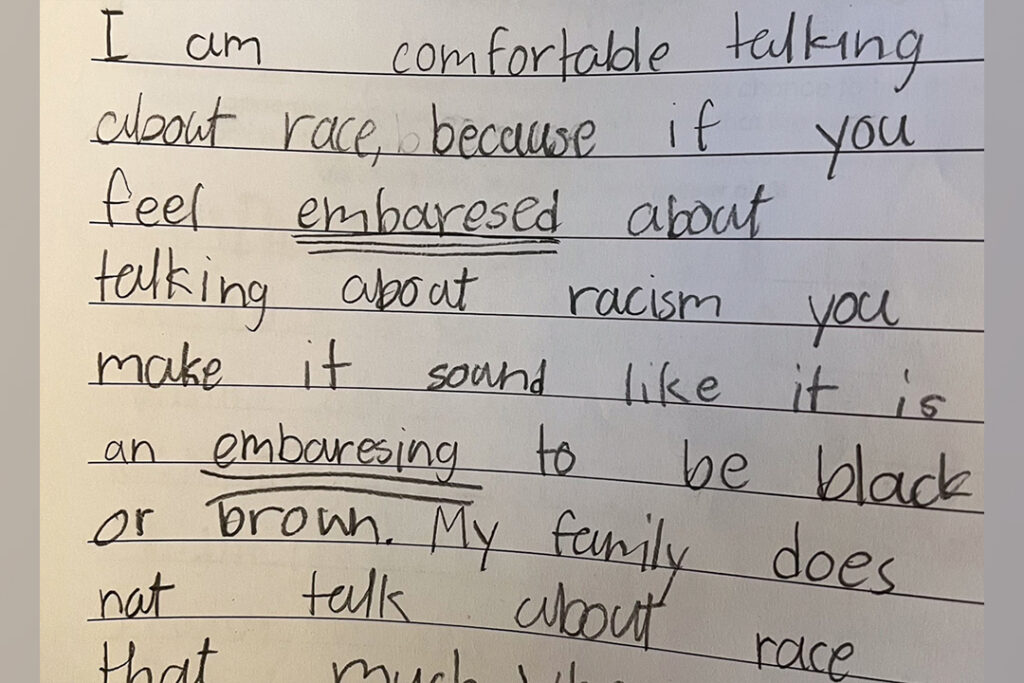

What I really want to make sure people know is that kids are ready for all kinds of conversations — even if you’re not. They have such compassion and are open-minded. They’re willing to see the world in lots of different ways and hold multiple truths simultaneously.

To take that opportunity away from them… it’s awful. If we ban certain types of discussions, we ban some of the proudest, happiest, most engaged times at school, when children are asking to address injustices past and present and asking those hard-hitting ‘why’ and ‘what if’ questions.

When they’re inventing and creating thoughts for the future like that, that is the most magical time. To not have that, it feels like you’re stripping it away from them. Everyone involved in a child’s learning has so much power. And teachers in their power can do a lot.

–Hannah Halpern

Third Grade Teacher

Washington, DC