I was in high school at the height of the AIDS crisis. And as a 13- and 14-year-old, I would sneak away into the city to meet up with this group of people, mostly gay men and Black women, who were part of ACT UP — a group who did intense activism around access to healthcare, specifically in terms of HIV/AIDS. In college, I worked for the Urban League and then the NAACP. And teaching is the perfect meld of all of those things: being on the ground, thinking about social change, trying to make an impact on the world without pretending you’re a savior. But I had to grow up before I realized that.

I went to graduate school, mostly because everyone else was. As the first kid in my family to go to college, I didn’t know what to do. I ended up getting a Ph.D. in Renaissance literature, and I finished grad school at the same time as the 2008 recession. My boyfriend at the time (now my husband) and I moved here to Boston for his residency.

Then the earthquake in Haiti happened. I was hired the day after the earthquake by a Harvard nonprofit called Partners In Health. They needed people who could write stories about what was happening in Haiti — that day. So for two years, I worked with a group of reporters to tell stories. It started in Haiti, and then in other parts of the world, and eventually I realized I didn’t want to be the person telling stories. I wanted to be the person in the stories.

I’d watch these nurses and think, ‘I want to do that.’ Not be a nurse, but be on the ground working with people. I think we put value on jobs, like there’s more value to being in an office or a cubicle and less value in being on the ground. Like there’s more value being in the ivory tower than building the tower. But the people on the ground redesign the gears. The mechanics are the thing that keeps the entire structure moving, and they’re the ones who can redesign the structure.

There’s this resistance to being on the ground when you’re somewhere ‘higher,’ but it is all I wanted: to be in the mix, making change.

I like reading and writing. And I thought, ‘How incredible would it be to spend my life reading books and talking about books?’ So that’s what I’m doing. I love teaching 11th and 12th graders because they’re weird and funny, and they kind of get satire (but not really). They’re still kids.

Students are dealing with complex social situations, especially in urban settings, where a lot of kids are forced to grow up a little faster. So it’s important to build curriculum and conversations that help kids navigate that without trapping the kids. It’s one of the things that we’re working to disrupt in secondary education: when you read the canon, the character kills or is killed. The narrative feels like this real set narrative. Instead, we’re working to keep the level of rigor while finding works of joy and inspiration.

Another thing we’re working on right now is how to teach kids how to write. I don’t think education has taught us a good way to pass on that skill, and what we’ve realized is that we don’t know how to do it.

I love AI. We’re going back to handwriting in class. It’s actually a huge relief. There’s a whole field of scholarship that talks about the connection between the movement of the hand and the brain. That’s why elementary kids really need to handwrite what they’re doing. We have this misbelief that kids have a deeper connection with technology — that they know how to type, they know how to research. But they don’t really.

Kids produce as much writing for 45 minutes on paper as they would have in one week on a computer, because you’re cutting out all of the distractions — on the computer, they’re bouncing around, trying to find other voices that they think are going to support what they’re saying, as opposed to just saying it in their own words. Getting rid of computers in the English classroom is a huge benefit of AI.

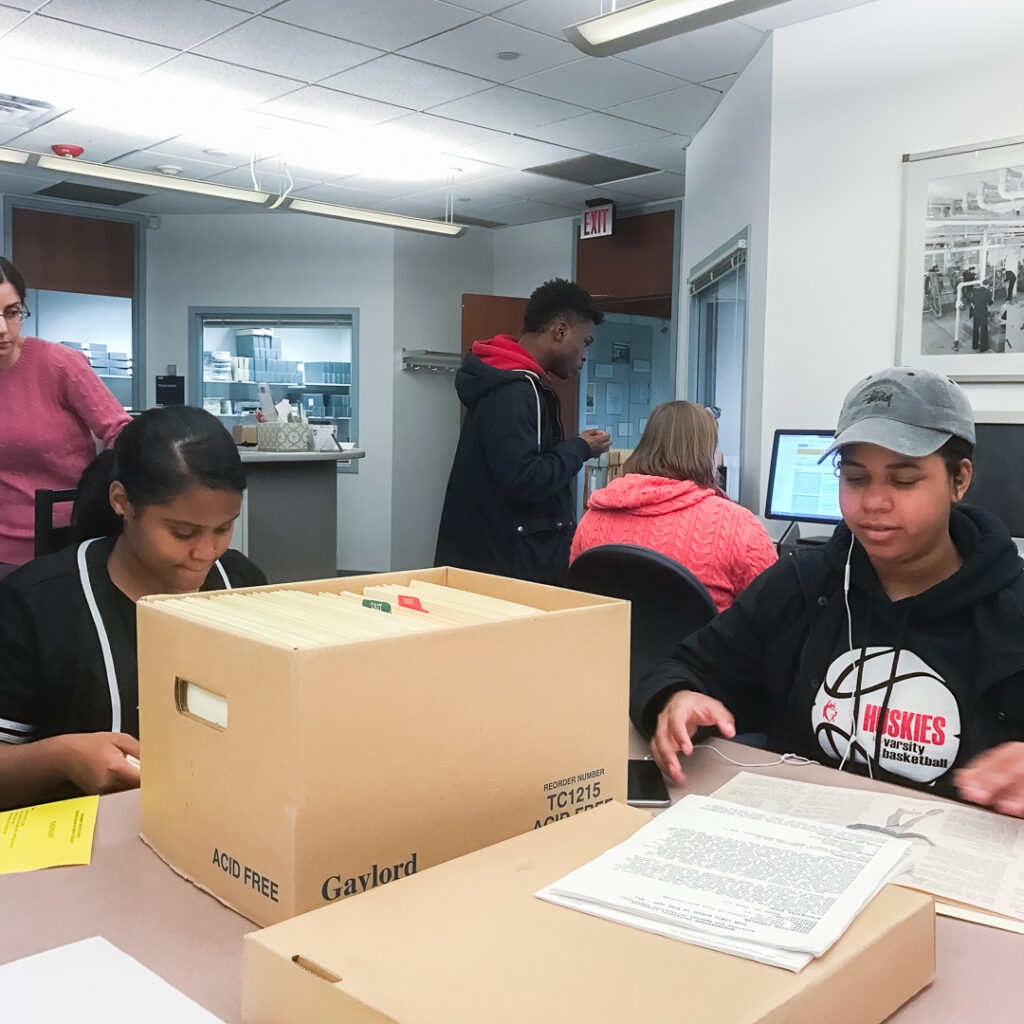

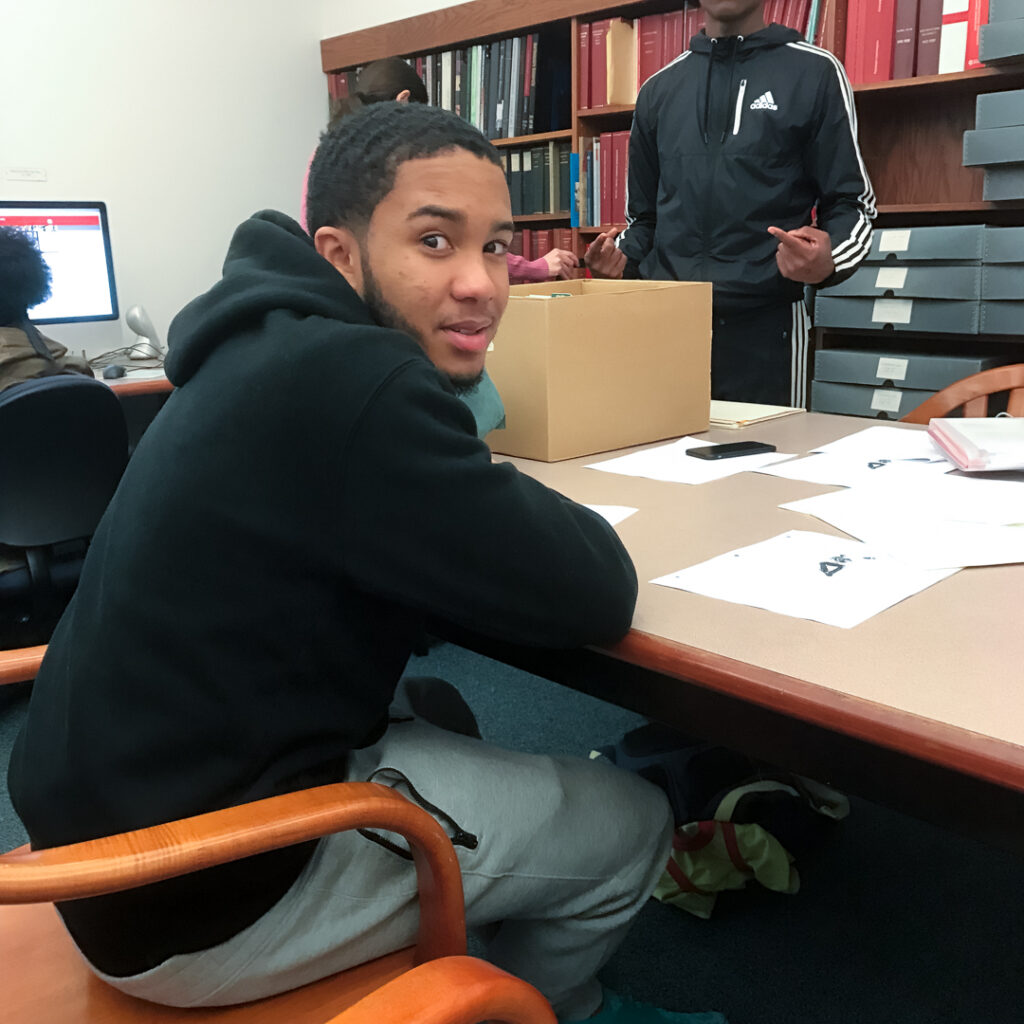

Teaching is often most fun when you are authentic with kids. That can happen a lot of different ways, and one of the ways is by creating the curriculum with kids. So last year, I realized I don’t have an Asian American curriculum, and I asked the students to co-design it with me. We had some graduate students from Northeastern come over to help too, and it ended up being this two-and-a-half-month journey. Kids were finding graphic novels, as well as pictures of Vietnamese and Chinese immigrants in Boston in old archives (because we were working with an archivist who helped us find primary source materials). As a group, we put together this collection of images and stories and videos and readings — things that we wanted to read that felt real to us.

We found joy and excitement, and at the same time we were creating something that felt real. And in making it real, the investment was really different than when reading Of Mice and Men. It allowed us to go deeper with skills. Kids were more invested in writing or reading or analyzing, because they were co-creating. And then at the end of it, they’d created something that we can use again and again, and the kids have their names attached to it.

So what you try to do as a teacher is create authentic experiences, over and over, for students.

School shouldn’t feel rote, and it shouldn’t feel static. It should feel like it transfers into the world beyond the classroom seamlessly. So we learn how to research something that’s connected to us and how to take a stance on it, and then how to express that through an act of advocacy. This is 11th grade English: practicing writing, research, and analysis. I want them to work on development of a stance: what is your take? What do you think should happen next?

This last month, the students learned about the history of exam schools (we’re part of an exam school). We read a whole bunch of primary sources going back to the 1850s of moments of attempted desegregation in the city. The fight for desegregation isn’t linear. It ebbs and flows. There are moments when society is more interested in it and less interested in it.

Our new admissions policy is focused on desegregation, so what we ended up doing was analyzing the new policy. Every student wrote a letter to the superintendent with suggestions of what they would add to or change in the admissions policy. And then the kids put the letters in an envelope.

As a side note, 90% of the kids had never addressed an envelope before. It was a 15-minute lesson on how to address an envelope. No one believed me that you lick the envelope to seal it, either. They kept saying I was gaslighting them: ‘She’s gonna touch this. Why would I lick something she’s gonna touch? Really?’ They were the same way with the stamps.

Anyway. The superintendent wrote us back last week. It was a long letter thanking them for their thoughtful writing: ‘This is a really complex issue, but we’ve printed your letters and we’re going to save them and put them in a file, and when we come back to this decision this spring, these will be a part of the artifacts that we consider.’

We all read the letter, and we talked about it. I asked them what it felt like. Some of them were angry they didn’t get a more direct letter, so we talked about what it would be like to write 80 letters to us.

What was most interesting to me was the number of kids who took a stance against the new admissions policy.

Before COVID, there used to be an exam that kids had to take to get into our school. And during COVID, they got rid of the exam, in part because it is a racist structure. It benefits those who can afford to hire tutors for the exam, and it benefits those who are going to a better elementary school — because elementary schools are neighborhood-based, whereas high schools are city-wide. So the new admissions policy changed to accept students by zip code: the top 10% of kids in every zip code gets into a lottery to enter one of the three exam schools. And some of the kids were saying, ‘That’s not fair. I had to take the exam. What if there are some idiots who are getting in, just because they live in a bad neighborhood?’

They wrote that in their letters: ‘This isn’t fair.’ Regardless of race or background, many of them were hardlining the protection of the systemically inequitable structure.

So I asked them about student loan debt, as another example. They said, ‘That’s different. College should be free. But getting into this place should still be like it is…’

There’s only so far you can push a 16-year-old to reason through something like this. But that’s what we try to do in class.

And there was another group of kids who wanted to get rid of the exam schools: ‘Let’s reimagine education, man.’

There’s a project-based school in central Mass that has no grades, where kids work in two-year cycles. At the start of each two-year cycle, the kids get a list of skills that they need to master. So by 11th and 12th grade, the kids are designing a massive project of their choosing — you could do a huge photography project, and I could do a baking project.

I visited for a week and shadowed a kid who built a pipe organ from scratch. When he’d go to his content classes, like English class, they would talk about a skill like developing a claim. But then what this kid would read in class was related to building a pipe organ. All the students read about things that were connected to their projects but practiced the same skills.

I think every school can do something like this: project-based, authentic, student-driven. These kids didn’t get grades. Instead, they had to present a portfolio of work at the end of a two-year cycle to their families and their teachers. They had to walk through and show how they had developed the required skills. When you find models like that, you think, ‘How can I begin weaving that into what we do? How can I slowly begin changing the thread of the conversation?’

One of the big debates we’re having in the high schools across the city right now is, ‘Should students be able to fail?’ There’s a pocket of us who believe that even if a student is at 60%, a D-, we don’t have the right to keep that kid from being gainfully employed after they graduate high school. But there’s this punitive mindset that’s so built into public education: this mindset of competition, this capitalist-induced mindset that we need to break away from. Capitalism really needs that D- student to be gainfully employed, so it’s self-defeating anyway. Kids aren’t competing against each other. They’re competing with themselves to learn. But everything we do wants to rank or to grade or to punish.

People are fleeing the field right now.

If you look at the big teacher prep programs here: Boston Teacher Residency, BU, BC… these programs can’t get people to apply. The Boston Teacher Residency used to have 65 teaching candidates. This past year, they had a dozen. Three of them were in English and two quit midway through the year.

We had about a third of our staff leave last year, at a school that would traditionally keep teachers for 20 years. We’re in full crisis mode. I don’t know what is going to happen. In Boston, we pay better than almost anywhere else in the country — for teachers, the average salary is well over $100,000. It’s not about the salary. It’s something about the constraints that people feel are put on them.

With 120-150 students on your roster each day, and with various duties and obligations on top of teaching, it is easy to make mistakes throughout the day. Unfortunately, the system is quick to discipline educators when those small mistakes do happen. There was a teacher who was late showing up to a hallway duty, because they were meeting with a parent of a kid who was in the hospital. A fight happened during that hallway duty, in the hallway where that person would have been, and they were charged with child abuse. They were charged with endangering children: ‘that child was punched in the face because of your negligence.’ That person was told they were directly responsible.

As union reps, we fought back hard against that language. In the end, the verdict ended up being, ‘While you’ve not been found guilty of child abuse, you have been found…’ And that’s in the official letter from the district, which makes it tough for that teacher to go to any other district. Imagine devoting your life to children and being accused of child abuse. With punitive measures being that intense, it’s scary to go into teaching.

It’s also a job that requires full commitment. I start working at 4:45 in the morning. My husband and I have a five-year-old, and once he’s down, it’s another two hours of work in the evening. I think there are a lot of people coming into the profession now who simply say, ‘I’m not doing that. I’ll be here to work during set hours, but I want to have hobbies, I want to hang out with my friends on the weekends.’ And it’s a job that doesn’t really allow for that.

We’re in Boston. We’re two miles south of the first public school built in the United States. What does it mean if a place like this can’t figure this out?

We have to figure it out. Because if we can’t make this work — l truly believe this — if we can’t make this work, then the whole thing falls apart.

If there isn’t public education, then the whole idea of a true democracy falls apart, because our democracy will immediately become a class system that can’t be anything but inequitable.

And sometimes it feels silly to talk at that level about what we do in an English classroom or a history classroom, but I don’t think it’s silly. I think the two things are directly connected. If you don’t have people who are angry and passionate on the front lines, on the ground, then it will fall apart. Because there is a deep desire by people in power to undo this thing. There are charter schools, private schools — there’s a trillion dollar education industry in the U.S. I understand why people want in on the money, and I understand why people are building schools. But what happens to our democracy if public education fails?

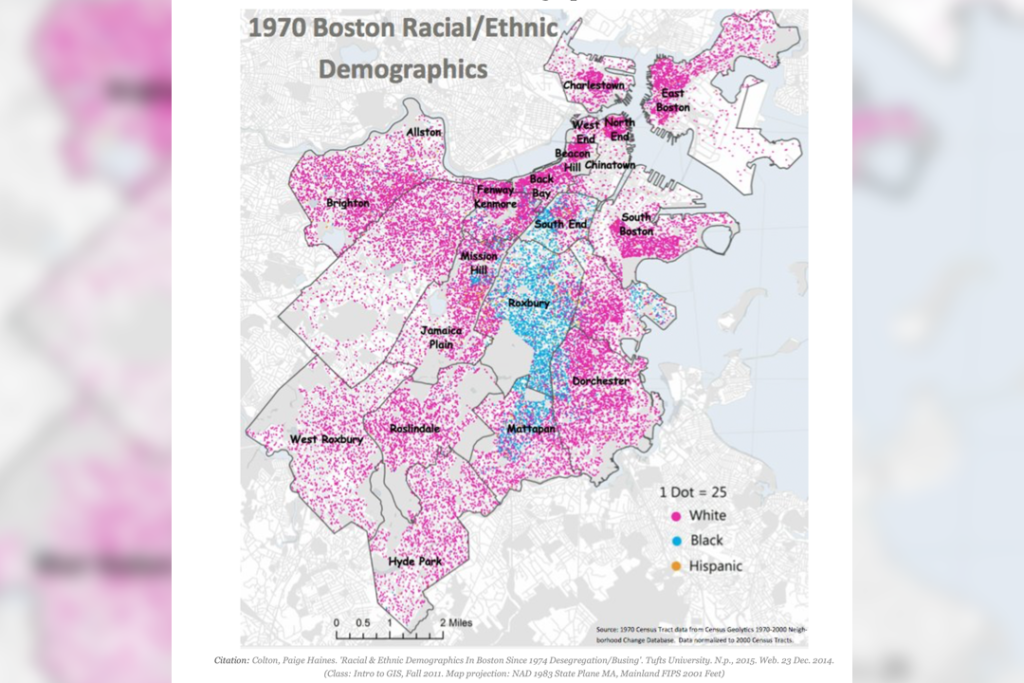

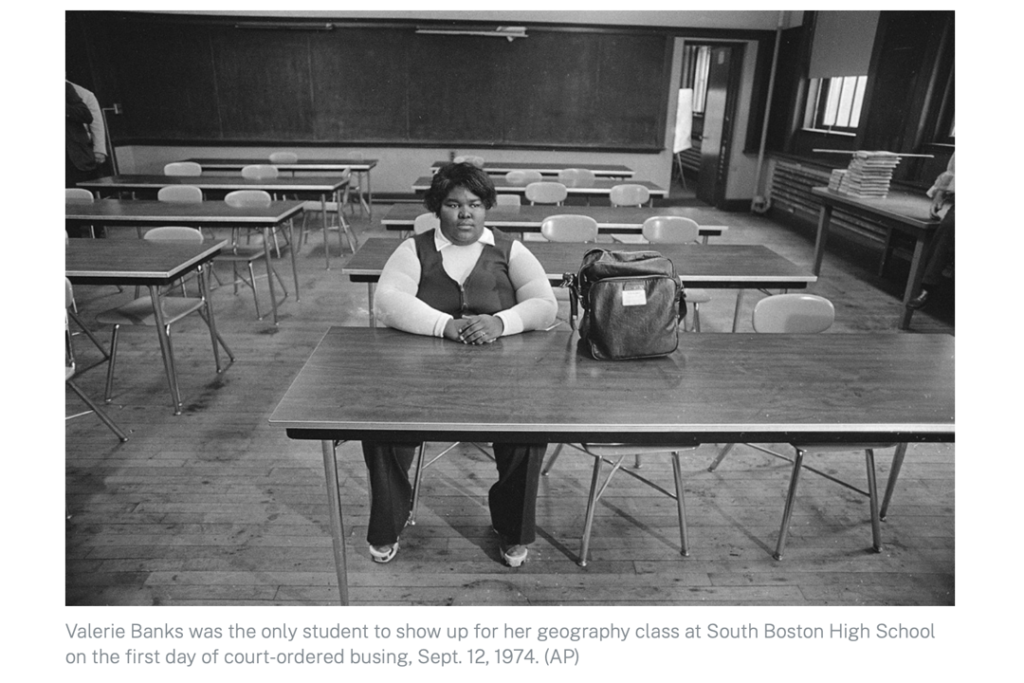

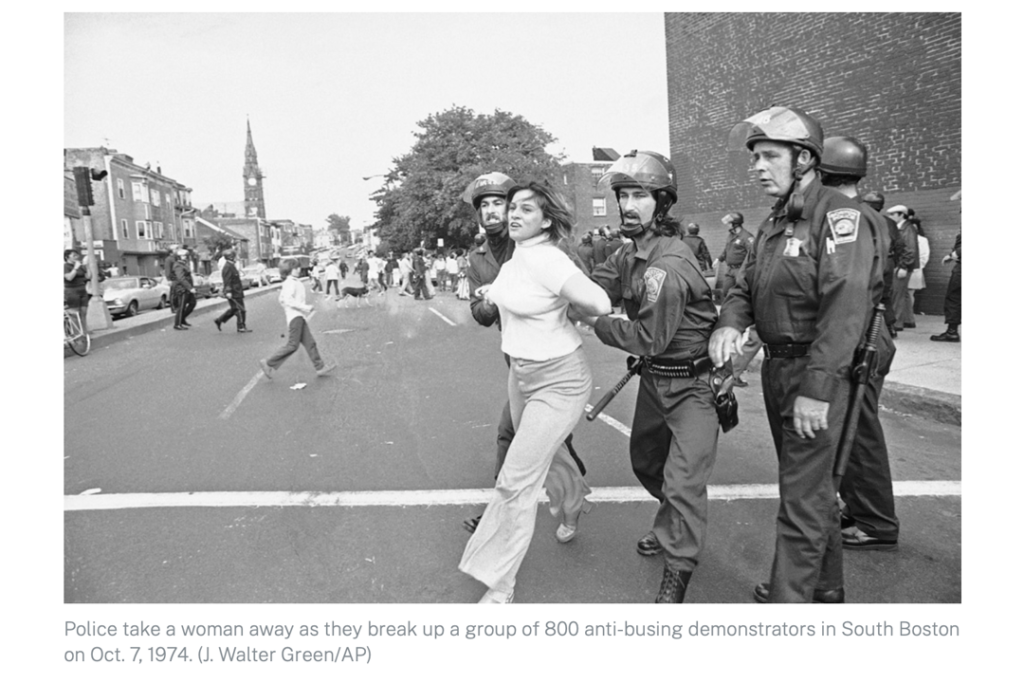

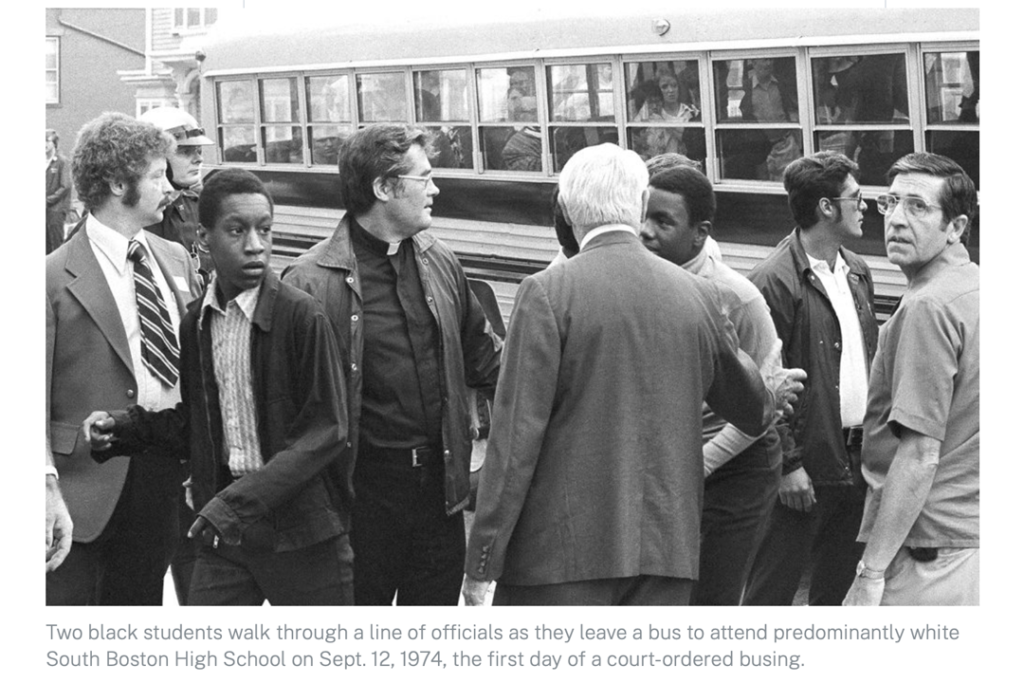

Boston was one of the last cities to integrate. It was a court order in 1974: Judge Arthur Garrity says the schools have to integrate. He gives the court order in August, and the schools have to do it by September. It’s an immediate turnaround.

In Roxbury, where we are now, there are 36 elementary schools that are predominantly Black schools. In response to the court order, the city immediately closes all of those buildings and razes them. They’re gone. They don’t exist anymore, as a preemptive measure to keep white kids from having to come into the Black neighborhood. So what happens is all the Black kids are bussed out to predominantly white neighborhoods.

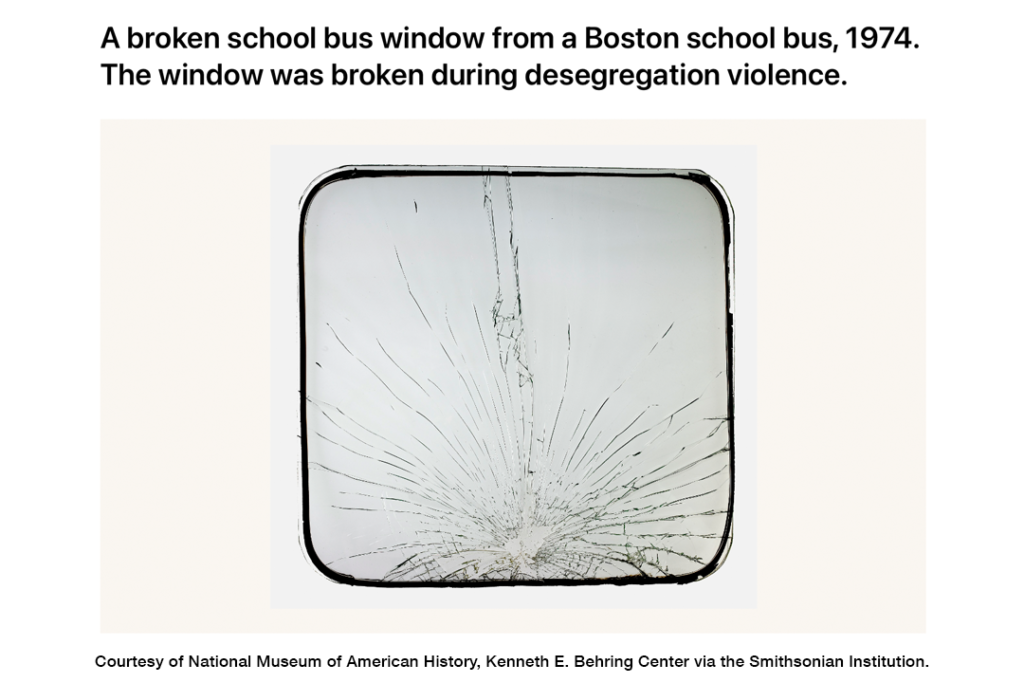

On those buses, going to a strange neighborhood, the kids have bricks thrown through their windows. They’re stoned. Effigies of Black kids are hung from trees near the schools where the kids are going, and they’re burned.

The kids on those busses are the parents and grandparents of the kids I teach. So if they are hesitant about having a white educator, that makes sense to me.

If people who looked like me threw rocks at you as a child, wouldn’t you be wary of me? It’s a fraught and deep thing.

All you can do is be your authentic self. You come at it with love and joy, and that hopefully comes through.

At the start of the year, between October and Thanksgiving, I write every single kid a one to two page letter and then sneak it into their backpack or books. It’s four a day that I do in the morning before school starts, and I find ways to sneak them in. They’re authentic. They’re like, ‘This is what I know about you. And this is what I think you will be in the world.’ It’s always nice to do it.

There’s a kid I teach here, let’s call him Aaron, who’s very quiet. I read his work, and then I wrote to him and I just said, ‘You’re quiet. But you’re a force. You’re thoughtful and kind and wonderful. And your ideas about what we just read are some of the smartest produced in this class. You should let your voice be heard.’

And he wrote me a long letter back. He said, ‘I think you’re the first teacher that ever recognized me.’

I had a student last year whose mom called me because she found the letter, and she was crying.

The reason I share this is because I think there are small ways that we can try to undo the violence of the past, the violence that took place in front of this building and other buildings around the city. It might feel like it doesn’t move the needle a lot. But I think it creates more space for trust and change.

So that’s what we do, as teachers. And we make lots of mistakes. But being part of a community means you have to be invested in the change and growth of that community.

This is my community. I want to make it a place where I can confidently send my own son to school.

–Chris Madson

English Teacher at John D. O’Bryant School of Math & Science

Boston, Massachusetts