Hurricane Katrina, COVID, and the Ten Commandments in New Orleans.

My mom has been teaching for fifty years. I grew up with her, literally grading papers and cooking at the same time. Back then, I never wanted to be a teacher.

In undergrad, I took constitutional law classes. During my senior year, I got disillusioned with it all, because it was so based on law and not the humanity aspect of it.

I called my mom, and I would frequently complain, and she said, ‘Why don’t you watch me teach, from an adult perspective, and see what you think?’ I did that when I was a senior in college. The space that she created was really human-centered. I decided, ‘I want to give this a go.’

I switched majors and when I graduated college, I started working in summer school and enrolled in a master’s program. I never looked back. I’ve been in the classroom since I was 21, so this is my 15th year. Once I got a taste of what it was like to be in the classroom, I absolutely loved it.

My mom taught many subjects. She taught special ed and social studies most of her life. I’ve followed the same trajectory. My first two years teaching, I taught special ed, and then I switched to middle school social studies and then high school social studies. High school social studies is where I am now.

When my mom retired, I applied for and got her position. I started teaching in the classroom in which she retired, which was awesome. It was like passing the baton from mother to son. (She decided to go back into teaching right away, though, and now she teaches religion at a Catholic middle school.)

To this day, she cannot go to the grocery store without people saying, ‘Mrs. Dier, Mrs. Dier!’ I thought as a kid that every mom was just super popular. Then I realized, ‘No, my mom is a teacher, and this is how teachers are respected within our community.’

I grew up in a working-class suburb of New Orleans. After Katrina hit, we lost everything. We lost our house. The community was devastated. We had to evacuate to Texas, and my mom got a job teaching at a school out there.

All of the teachers in Texas mobilized to help us out after Katrina. The English teacher had supplies ready for us. The art teacher had paintbrushes. The whole school got together to give us backpacks and other things we’d lost.

Before Katrina, I loved playing soccer. When the soccer coach found out, he bought soccer cleats for my brother and me so we could play again.

That’s when I realized how teachers mobilize in so many different ways, beyond just showing up in the classroom. They’re community activists and advocates, and that’s why teachers are so overwhelmed sometimes.

I went to East Texas Baptist University, and when I graduated, I really wanted to be a part of the rebuilding process after Katrina. I felt like there was a certain type of call to teach in the area code in which you were raised. There’s also something bigger in New Orleans, in terms of teaching in a community that has experienced collective trauma in ways we’re still grappling with. I felt it was even more important to come back to the area that raised me to get involved in education.

Students come in with all kinds of issues, problems, concerns, and dilemmas, and so I try to be like those teachers in Texas who stepped up to the plate. I try to carry that legacy and the legacy of my mom. As devastating as Katrina was, I think it kind of pushed me to this trajectory, even if I didn’t realize it at first.

I was teaching when COVID hit. I taught seniors, and I’ll never forget walking out of the building that Friday when we shut schools down in Louisiana. It felt eerily like Katrina. When they said that they were going to open schools back up on April 16, I just knew that wasn’t going to happen.

As we were walking out, I remember talking to seniors and feeling that sense of dread I felt when I was a senior during Katrina. That weekend, I wrote an open letter to seniors that talked about my experience and the trauma I felt back then and how I navigated it.

When I woke up the next day, the letter had gone viral. That devastating experience during Katrina helped me uplift others. I knew what it was like to lose my senior year. I spent so much of the first few months of COVID hopping on Zoom calls and talking to schools around the country. Katrina and COVID were unique experiences, but they both carried that sense of loss.

Back in college, I remember sitting in a constitutional law class where we were debating about people burning draft cards. I was the only one arguing for why we should put it in the context of the situation, and empathizing with the people who were making this statement and why they were breaking the law.

I remember my professor and all of the students saying, ‘That’s very nice, that’s very noble, but the law states…’ and I was the only guy who was saying, ‘I get what the law states. But when you think of what the Vietnam War was, doesn’t it make some sense to you?’ I made parallels to other movements of civil disobedience, and I remember asking them, ‘Do you feel this same way about people crossing the bridge from Selma to Montgomery?’ I wasn’t trying to minimize the law profession by any means. It left me wanting more.

I called my mom after that class, and she started to nudge me (very gently) to the path of education. She’d never done that before. But later she said, ‘I always knew you were going to become a teacher. You just had to think of it on your own.’

The Louisiana legislature passed a law requiring teachers to display the Ten Commandments in the classroom, at a certain size, front and center. Many teachers were upset by this, and the ACLU immediately sued on behalf of parents.

It’s blatantly unconstitutional and is a clear violation of the Establishment Clause. It’s harmful to students, especially students who don’t abide by that religious belief. It signals to students who are not Judeo-Christian that their religion or way of life is inferior to others. More specifically, it signals that Protestantism is superior because the state’s required wording is not the wording recognized by Catholics or Jews.

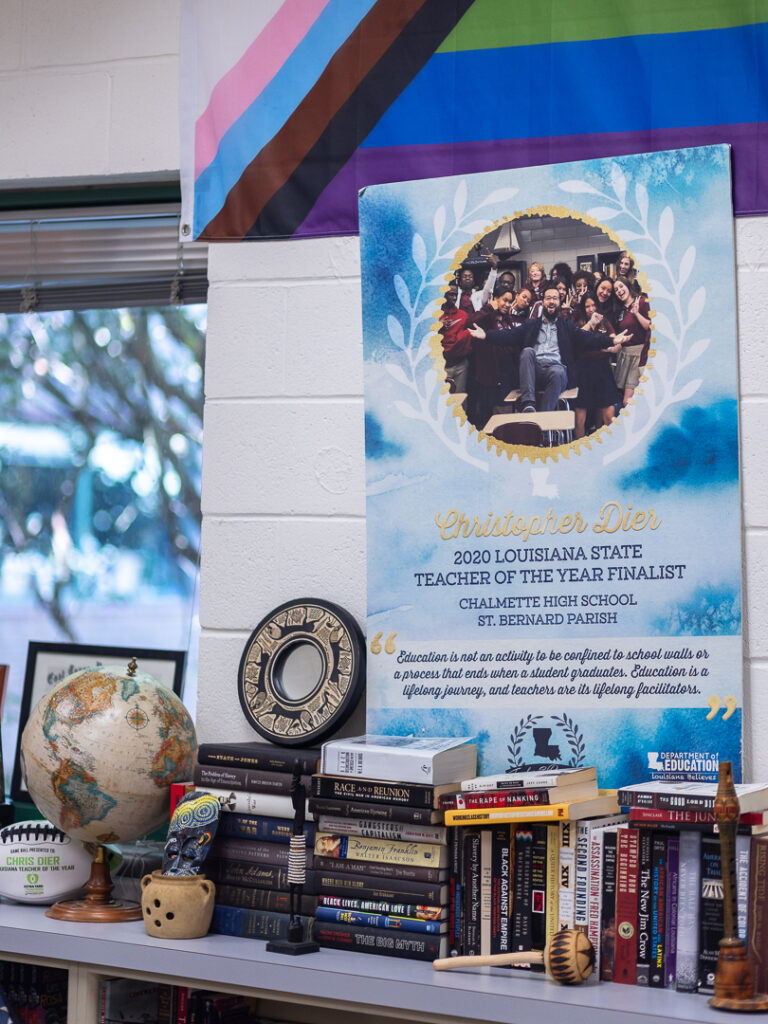

When the law passed, a multinational law firm contacted me and asked if I would be a plaintiff as Louisiana’s 2020 Teacher of the Year. I agreed. I’m incredibly apprehensive about it, but at the end of the day, I know that if I’m going to be a teacher like my teachers were for me, then I have to fight for my students, especially when it feels uncomfortable. I’m not fighting against Christianity; I’m taking a stance against Christian nationalism.

I feel it’s a duty of a teacher to stand up when we can, regardless of the backlash. We know through countless studies that if students don’t feel validated, heard, or seen, then that’s going to impact their self-esteem, which is going to lower their ability to perform in a classroom.

This law is masquerading as the idea that we need more morality in our schools. But the reality of it is, it legally coerces teachers into the role of messengers of a specific religion. It’s asking me to compromise my values and the psychological safety of my students.

The Ten Commandments law isn’t the first time my classroom has navigated difficult legislation. Last year, one of my students notified me that they were planning a walkout to oppose Louisiana House Bill 570, one of many anti-transgender bills circulating nationwide. The bill states that when a student confides in any adult at school about their gender identity, the teacher is required to inform their parents. But the fact is many students confide in teachers because they’re not yet ready to share that information with loved ones, and they may be struggling with depression or thoughts of suicide.

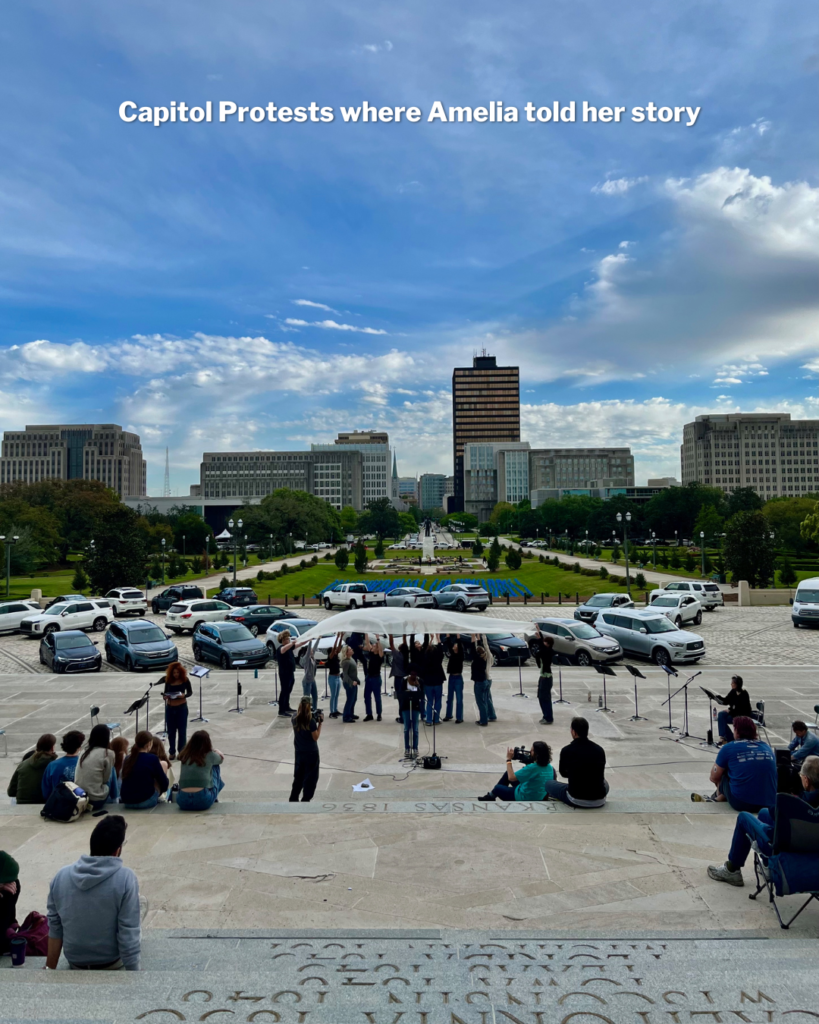

This student, Amelia, was incredible. She and the other students decided to protest similar legislation at the State Capitol earlier this year.

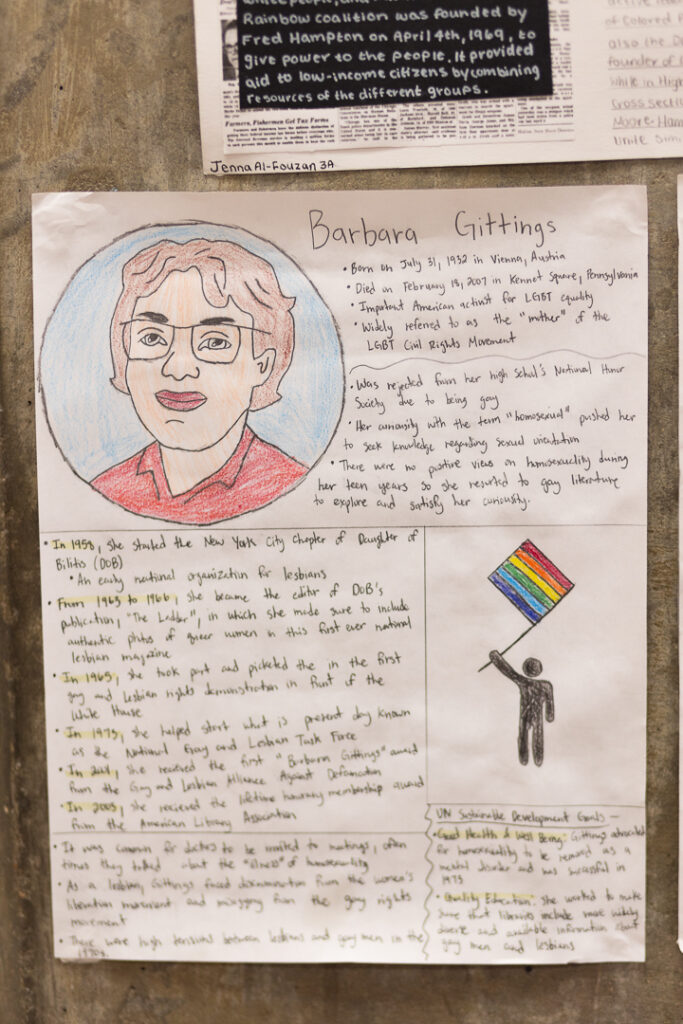

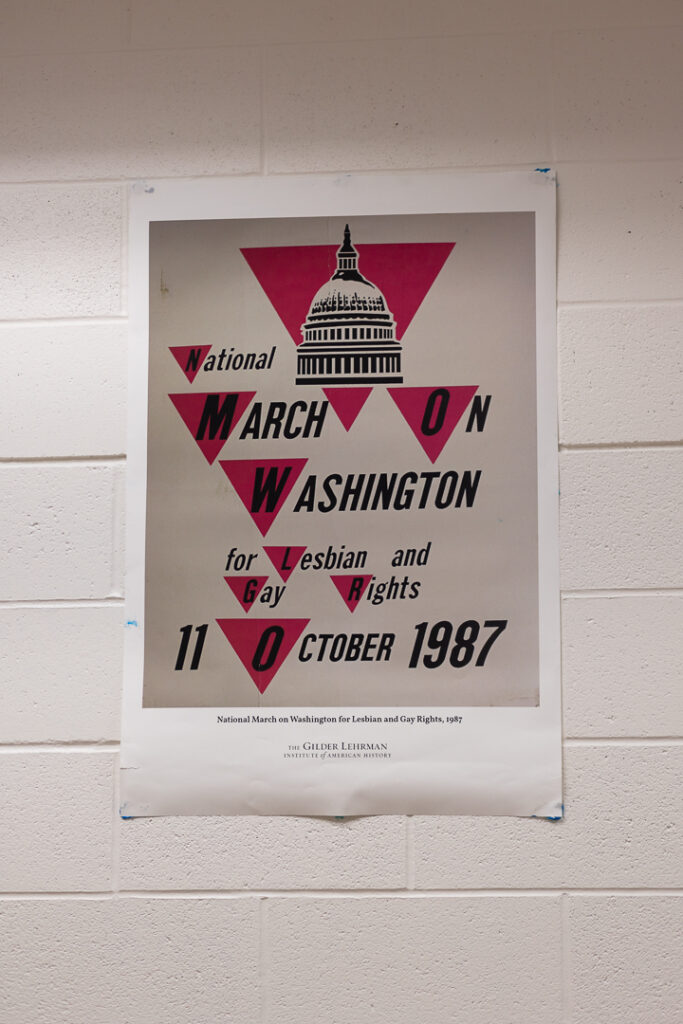

On the steps of the Capitol, Amelia gave a speech, and she spoke about an experience she had in the classroom. She said, ‘I’ll never forget my sophomore year going into a classroom and looking up and seeing a poster about the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987. It’s something special to be in a space where you enter and automatically feel safe and respected, and where the teacher not only believes in ideals that make you feel human, but is going to display those ideals so people can see that right when they walk in.’

It was so powerful to see a student protesting this harmful, dangerous legislation, and to hear that she’s doing it because she wants every student to feel how she felt in my classroom. I think that moment is going to stick with me forever.

New Orleans is a unique city in many ways, and things here function differently. We take food, dance, art, and culture incredibly seriously, but in some ways, not much else, which can definitely cause problems. New Orleans has a lot of poverty, and with that comes its own issues. We also have collective trauma. Anyone who’s been here for 20 years shares a similar experience because of Katrina.

Families are amazing in New Orleans. Oftentimes, students’ families will cook for me or invite me to events. I really enjoy the people here. I can’t imagine being anywhere else. They’re huge in terms of their support and their care. I’ve had such good memories and relations with the families of the students that I’ve been privileged to serve.

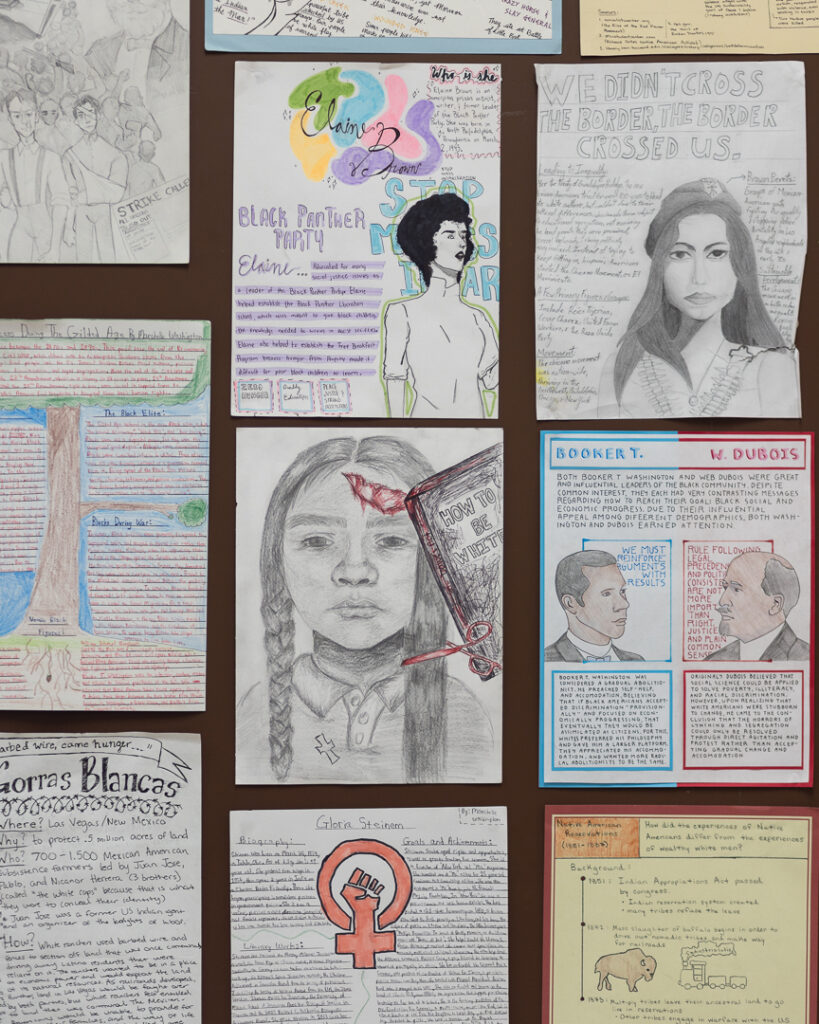

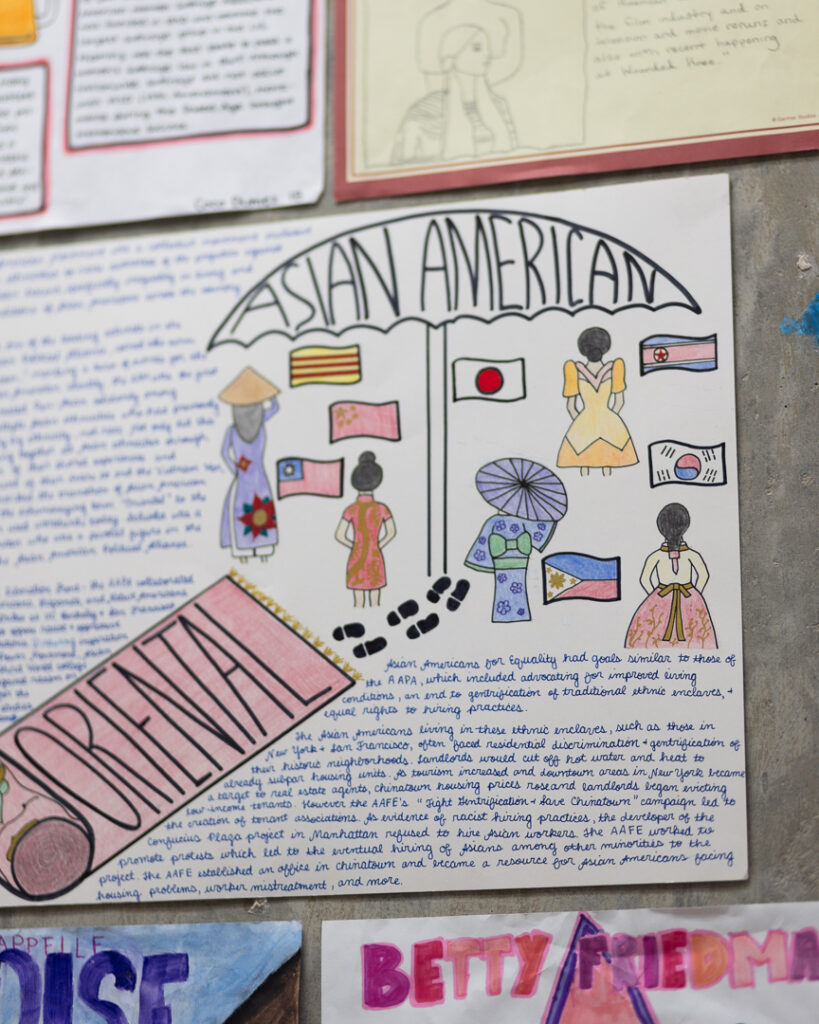

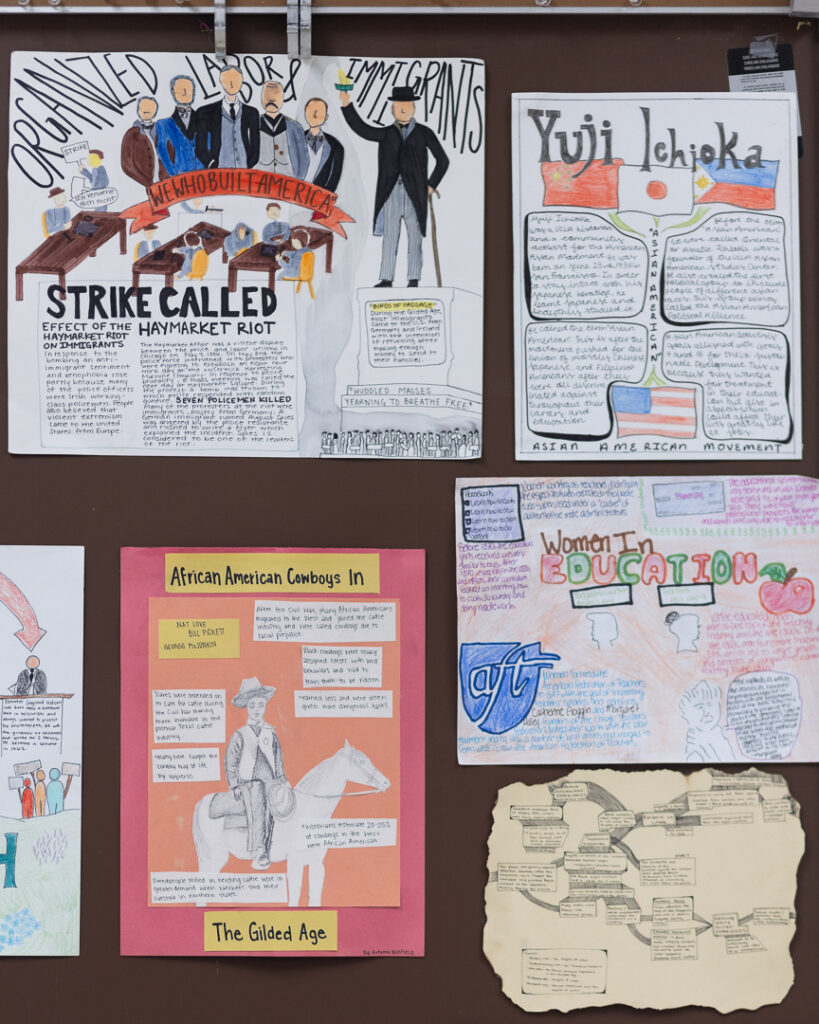

I’ve never had a parent complaint. I’m very open about what I teach. I share my year-long calendar with students, admin, and parents. I follow the curriculum closely while incorporating things into that curriculum as well that I think deserve attention. My number one goal is to help each student feel seen.

Louisiana has a teacher shortage, and we know what can be done to make it better. If you pay teachers more and give them a better standard of living and smaller class sizes, teachers are more willing to stay in the profession. We know that’s the fix, but we know that’s not what our politicians are doing, and so we have to come up with our own ways to try to figure it out.

There’s a program called REACH University that offers districts an opportunity for the people who work in their classrooms to become teachers. It gives paraprofessionals and aides a pathway who wouldn’t otherwise have one, because colleges are expensive, or they’re working full time, or they have kids. It allows them to go into a program where professors teach night classes virtually, and for an incredibly low amount of money, they can get their bachelor’s degree to become teachers and increase both their income and their staying power. I’d like to see more programs like that.

Teaching gives me hope in ways that nothing else does. Teaching younger people and seeing that they’re passionate, and they’re ready to make changes and they’re ready to work hard, is incredibly motivating.

–Chris Dier

Teacher at Ben Franklin High School

New Orleans, LA