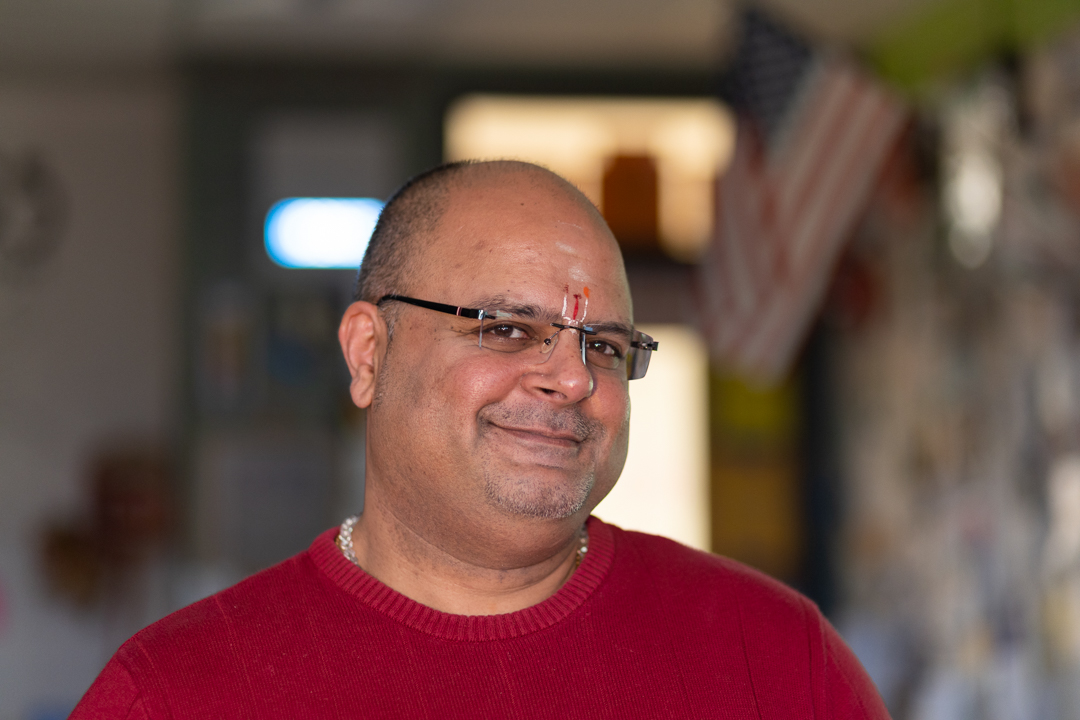

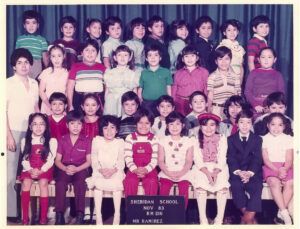

I grew up in Oak Park in the 1980s. People were all about the melting pot. The idea was that everyone is the same and nobody looks different — we’re all part of this collective homogenous blob. One of the drawbacks to that was that I was never really seen.

I remember this time in first grade: I was sitting at lunch by myself, eating a sandwich. And these four fourth graders came up to me and started calling me ‘dothead’ and ‘sand N-word.’ I had no idea what was going on. They broke my lunchbox. And I remember the adults just standing there, watching it. I also distinctly remember getting yelled at by my mother after school, because the lunchbox was broken.

I think back to that time, and now that I work where I grew up, I don’t want another kid to have to go through something like that and not feel seen. I went through a large chunk of my time in Oak Park never having a real conversation with anyone in a position of authority — falling in between the cracks. That’s part of the reason why my approach to teaching is highly individualized: talking with every student, individually, as a person. Trying to have a meaningful conversation with a student every day. Because that’s something I never experienced.

The growth that you want to see with a student doesn’t always happen right away. But if you continue to have those conversations with students, eventually the seed is going to germinate. Eventually, the bud will open up. But that only happens with time and effort and being able to individualize an approach where every kid is seen. And every kid is valued and honored. And no kid feels like they just exist.

I came out of undergrad in 1995. I was at the tail end of this idea that if you did everything they said (whoever ‘they’ might be), you’d be fine.

Your job was to exceed the previous generation — so if the previous generation cleared $100,000, your job was to clear $200,000. The metrics for success were externally defined. You do X, you’ll get Y, and that’s it. But my life never really worked that way. I never quite understood why. I always felt that I’d done everything that was asked of me. And I still came up short. So I internalized that as my own shortcomings.

But when I landed in teaching, that was the first time I was able to understand that perhaps this notion of what ‘they’ say might not be how I want to live. And that maybe I wanted to get off the treadmill of other people’s expectations.

When you work with a child on such a nuanced level, only you can only understand what that success looks like. And you can’t transmit it to anyone else. You can’t explain it without people giving you a look like, ‘Whatever, weirdo.’ And that’s where as a teacher you start shedding the external expectations, because your metrics for success have now become internal.

I think that’s why, spiritually, teaching ended up being the place for me. It was the one endeavor I tried where I could look at myself in the mirror and not feel bad about what I did that day. I may have failed, but I never felt bad about what I was doing.

When I first started teaching, I was pretty atrocious. But I always felt the need to come back day after day and be less atrocious. I had never experienced anything like that in my life.

Teaching taught me that failure can have something redemptive and restorative in it. I think that’s what attracted me to it. And to this day, I think that’s why I still do it.

I remember distinctly taking every single thing that had happened during the day and poring over it, every single night. My day would be done at 4:00, and then I would go from about 4:10 to 2:00 a.m. as a new teacher, asking myself, ‘Why didn’t this work? What else can I try?’

In your mind, you take home the curriculum, the students, your personal failures — and the successes, but sometimes the successes feel rare. In a culture that is so driven by the fruits of labor, and the idea that ‘I want to get what’s mine,’ you just can’t get that in teaching. You’ll never get that in teaching. Epistemologically, existentially, you have to gear yourself toward the idea that your shortcomings are a constant companion.

You can only take sanctuary in the fact that you did your job today, and you’ll do it a little bit better tomorrow.

One of the most important things I’ve learned about teaching is that you don’t know what you don’t know. Because every single moment, you’re having to connect your content to the nuances of a child’s mind. And we will never know what they’ve experienced. We’ll never know if they went without food that morning. Or if they were in transitional housing, or what emotional abuse they’ve endured.

I can’t imagine what it’s like to go through middle school with social media replaying every one of your mistakes — constantly on loop, being reminded that you are always less than. I don’t know what it’s like to be a 14-year-old today. I just don’t know.

I think that’s why I would slightly push back on the idea that anyone can be a teacher. Because you have to be a person who’s okay with uncertainty. You have to be okay with ambiguity. And you have to live at the hyphen of being a practitioner, an action-based theoretician who’s grounded in reality — you live in all those hyphens because you just don’t know. And what you do today, it may not materialize. You may not see the effects for a while. And you have to live with that.

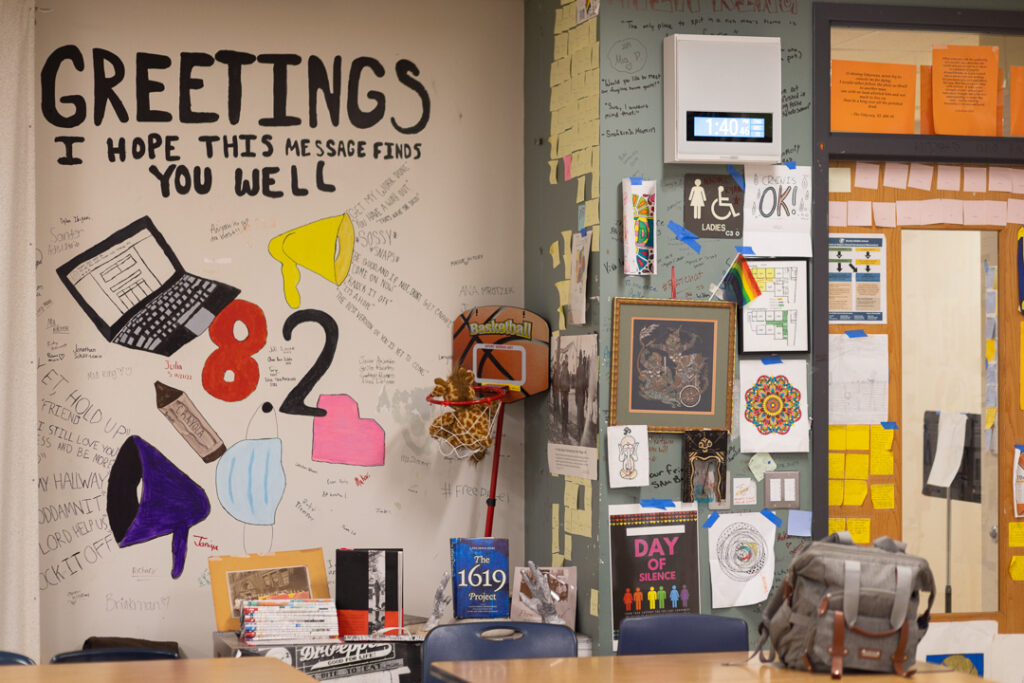

One of the things I would suggest about teaching is that every teacher shows you what their core values are. They may not post them in the classroom, and they may not explicitly say them, but they carry their values with them in how they interact with people and how they interact with children. You know the results of their philosophy by the way they enter the room.

And if your core values include, ‘If I do everything right, then I’m all good,’ I don’t think you’ll make it. Because the sea of uncertainty and the sea of what you don’t know is far bigger than our little boats. You can’t control this. It’s like trying to empty out the ocean with a tablespoon.

I hear a lot about how teachers get summers off and get off at 3:30, so anyone could do it. But if you take that philosophy, you have a shelf life. And that shelf life is about two to four years, because eventually, it will wear you down. You have to instead shed the label of certainty and absolutism. You have to be able to keep that wonderment and joy about you and model it to the kids.

And in a way, if you know that the institution is not fully serving the needs of children, you’re either on the side of the institution or you’re on the side of the children. There are ways to permute it. But if you know that the institution is doing real harm — doing real harm to children who are on the LGBTQ spectrum, children who are on the different modalities of learning spectrum, Black children, brown children, poor children, transitional housing children — if you know that the institution is doing harm and you can’t change the policies or the structures, you need to make your choice.

I’ve made my choice. And if anyone wants to join me in having a conversation about vulnerability, about placing students at the center, about how to become an architect of castles and cathedrals dedicated to student growth and student honoring and student voice, I’m here.

I had a student six or seven years ago who was the first student that came out to me as trans. They were very specific about wanting to be called by a new name: ‘I’d like you to make sure that you refer to me like this in my work and my documents.’

I didn’t have an awareness. At the time, we were just coming to the idea of students being non-binary — the idea of preferred pronouns and preferred names. Back then, I don’t think we really understood it. I remember saying it wasn’t a problem — that I was fine with whatever they wanted to be called. It wasn’t like I had some deep, profound philosophical platform. It was just like, ‘Okay, that’s fine.’

But I remember hearing other adults talk derisively. They would say hurtful things and continue the practice of deadnaming. And I let it go. I didn’t really say anything to the adults. I didn’t have the gumption to go to them and say, ‘Stop doing that.’ Maybe I wouldn’t have been able to change their behavior, but maybe I would have been able to provide a space and a structure where children felt completely validated and honored.

It influenced my teaching because now, looking back on it, I realize that I should have done more. I should have done more with the adults and taken them to task. I should have been a lot more forceful, not just in working with the student, but also working with these human beings who were dismissive of what a young person needed from them. It influenced my practice, because ever since then, I’ve been this incredibly powerful advocate for students. It’s almost been a ‘damn the torpedoes’ approach. I’ve accepted the fact that it’s completely okay if other adults don’t understand what I do, or even if they’re derisive toward me. Because as long as I can be a buffer for those kids, for any kid, I’m good with that.

Kids will come up to my room during lunch. I’ll supervise kids in the stairwell or in the classroom, because that’s what they need. I don’t want to have another moment where I wake up and look in the mirror and feel guilt-ridden that I let some young person down. I want to help them be able to advance through this forest of pain called middle school.

So when students wanted to form an LGBTQ safe space, I said, ‘Yes, let’s do it.’ When students came to me and said, ‘I wish we had a class where we could talk about issues of race,’ that’s how my African American Studies class came about. If it turns out that only one kid doesn’t feel the need to harm themselves as much because they’ve got a space they can turn to, that’s okay.

It’s breaking down that treadmill of expectations again: ‘If you do what the adults in power say, everything will be fine.’ No. It’s not true for me, and it’s not true for the students. If there was any lingering doubt that the adults knew what they were doing, the pandemic torpedoed that. It became really clear to students that the adults in charge may not know much more than the kids.

The system of education has remained strikingly the same from 1880 to now. And that’s a problem. If you’re still teaching pre-nuclear age, that’s a real issue. So on some level, you do have to make a conscious choice. I remember hearing someone say a couple years ago, ‘I’m going to be a good soldier.’ But if anything has been proven over the last couple of years — from the pandemic, to our collective awakening regarding issues of social justice — being a good soldier in a losing war effort is morally and ethically unacceptable to the next generation. Why would we want to be an example of what doesn’t work?

My experience with students and their interactions with adults breaks down into one of two camps. Either they find adults who are blessings or adults who are lessons. Their blessings teach them how they’d like to be when they grow up. Their lessons teach them how they do not want to be when they grow up. And I’m not sure where I fall, but I know where I don’t want to be.

I’d like to fix my compass to the North Star of students, regardless of what the adults do, because in the end, it’s what those students will remember. You know, middle school is a time of life where so much is airbrushed out of memory. Kids don’t want to remember much of anything about middle school. But if we’re able to create one or two memories that withstand the airbrush test, that’s good. Because 6th, 7th, and 8th are horrific. That’s why we need to be doubly mindful of what our role is and what we have fixed our North Star to.

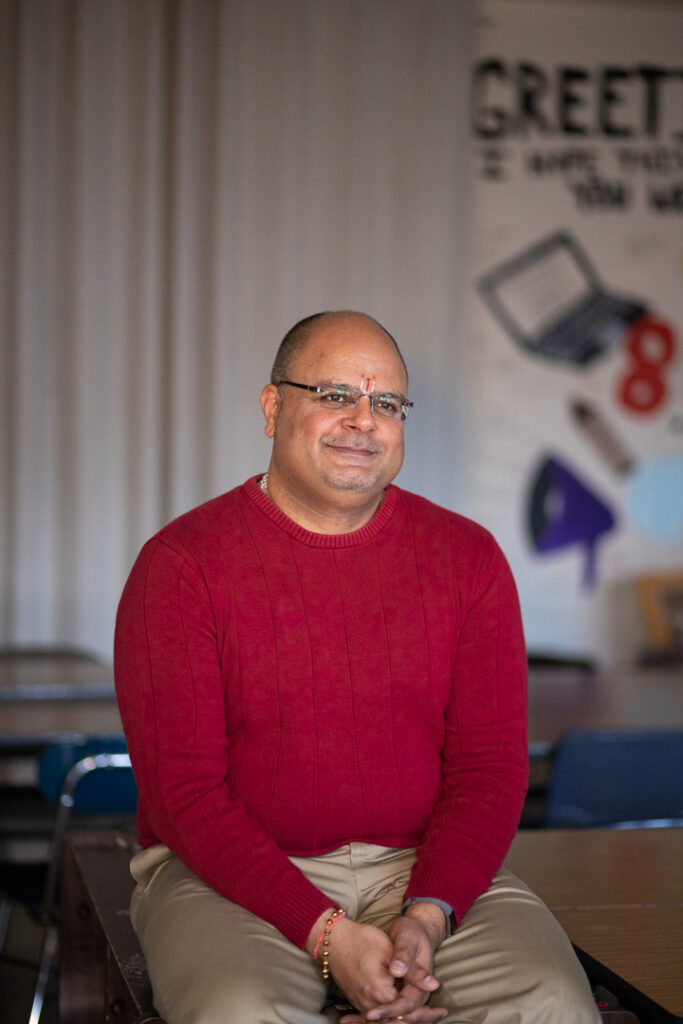

I wish people understood that teaching is about the presence of a soul. It’s about a teacher believing that they have a soul and being comfortable enough to bring it into the space. It’s about adults understanding that kids have souls, and that they are struggling to discriminate between the real and the unreal. Students need help understanding that there are things that are temporal and things that are permanent, and that we can latch ourselves on to the things that are permanent and allow the temporal to fall off to the wayside.

Good teaching, in my opinion, is a soulful exercise. You cannot talk about the idea of making teaching into a science, where every teacher has to teach the exact same thing in the exact same way in the exact same manner. This is not creating widgets, tables, or chairs. You’re creating human beings. And as great as my content is, it doesn’t take the place of the soul of a young person. What I teach is secondary to who I teach.

I remember before I started teaching, I was sending out at least 50 resumes a week. And I was getting rejection upon rejection upon rejection, and I was sending applications all over — private schools, public schools, suburban schools, urban schools, anywhere across the country. And I got a rejection from a school in Columbus, Ohio. It was a handwritten rejection from what had to have been a nun. It was perfect penmanship. The cursive was to die for. And I remember she ended it by saying, ‘Good luck in your pursuit of God’s calling.’

And even at 22, knowing that I needed to find work and knowing that American Express had a hitman out looking for me, that just stuck with me. God’s calling. It is the most intimate act possible, to be able to peel something off of your mind and your soul and impart it to another human being. It is a pride-swallowing siege every single moment. And it is a test of your soul.

There is no such thing as summers off. There is no such thing as getting out at 3:30. Because it’s your soul. I can’t leave it at work. And my wife gets infuriated with me. She says, ‘I married a doctor without the money.’ Because you’re always on call. You’re always on call for the kid who says, ‘I’m not feeling good right now’ or ‘I’ve got the blade to my skin.’ ‘We got evicted last night.’ How do you turn away those calls? What kind of person would do that?

I wish people knew. Not for any accolades. But to stop the excessive encroachment and the false certainty of, ‘Oh, I totally could do this.’ Oh my gosh, try.

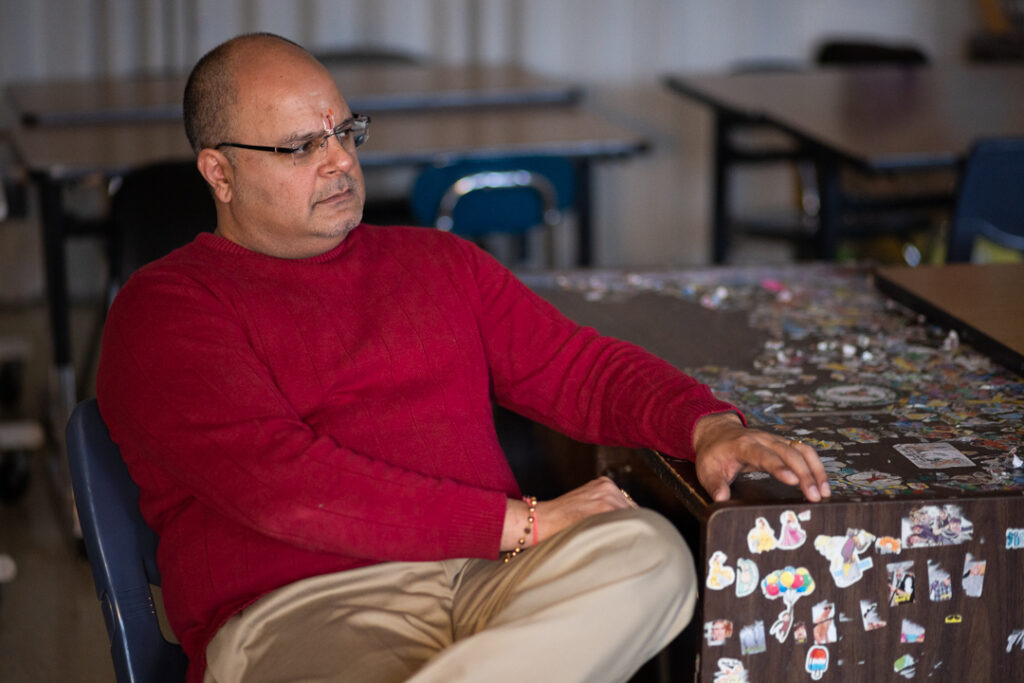

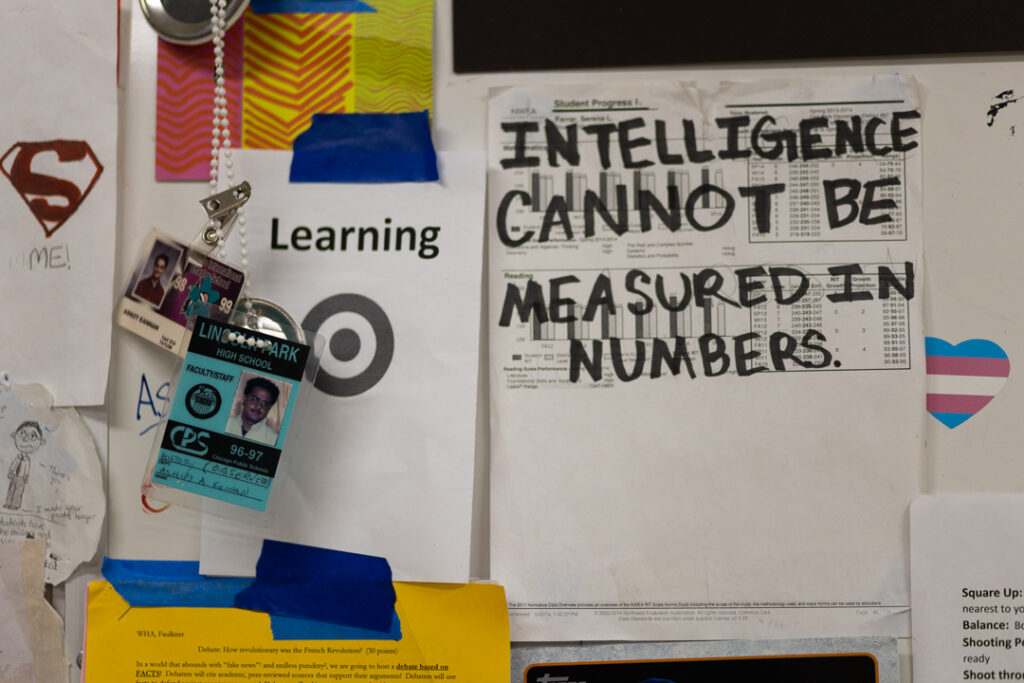

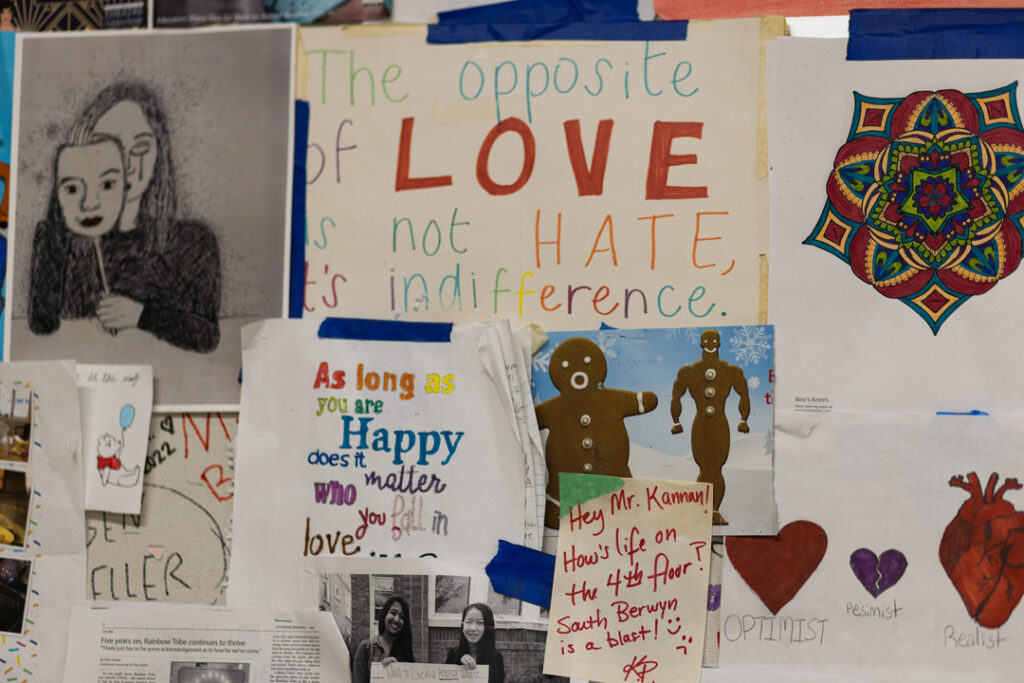

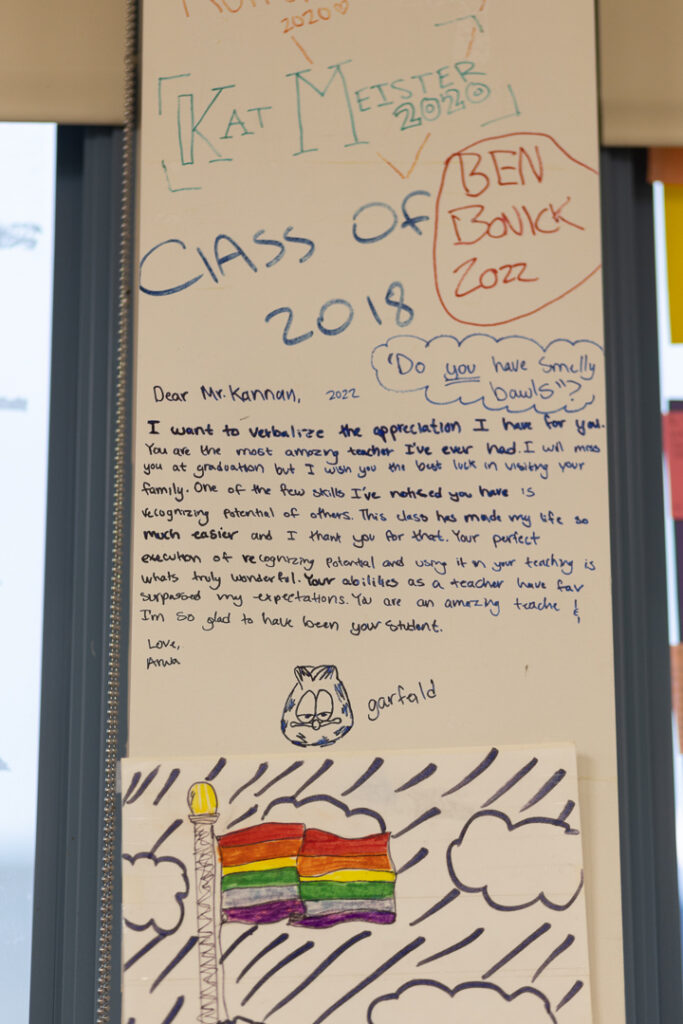

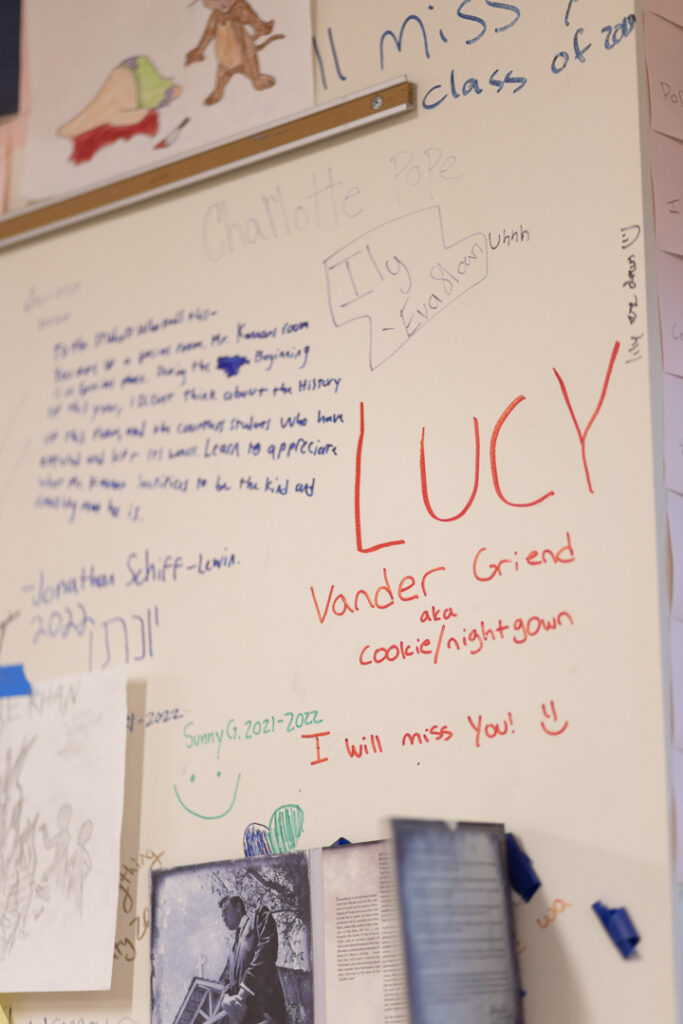

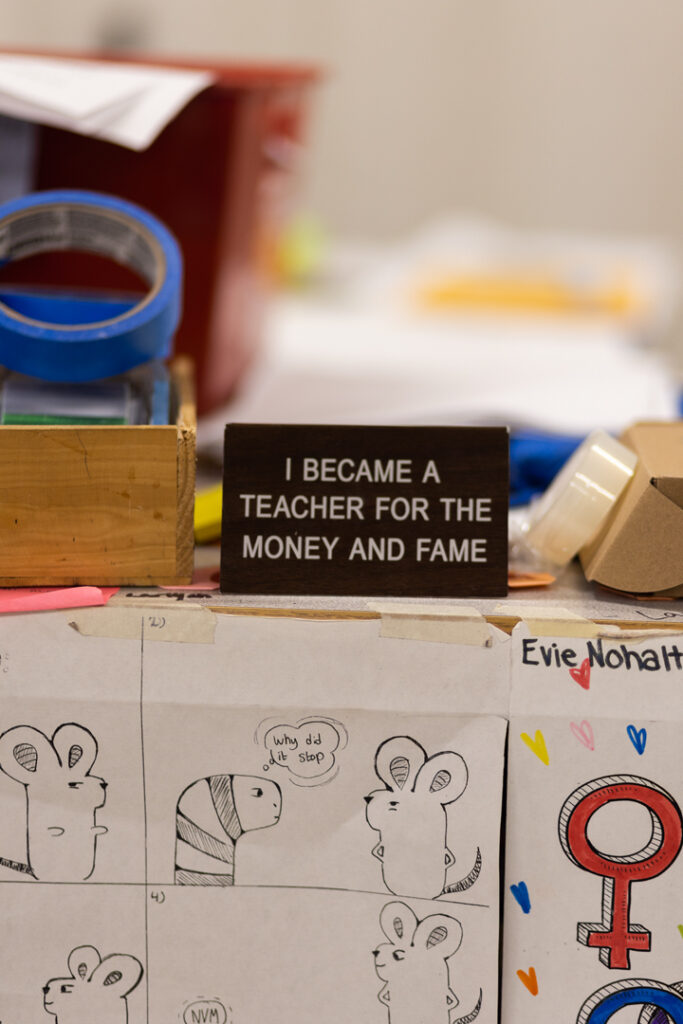

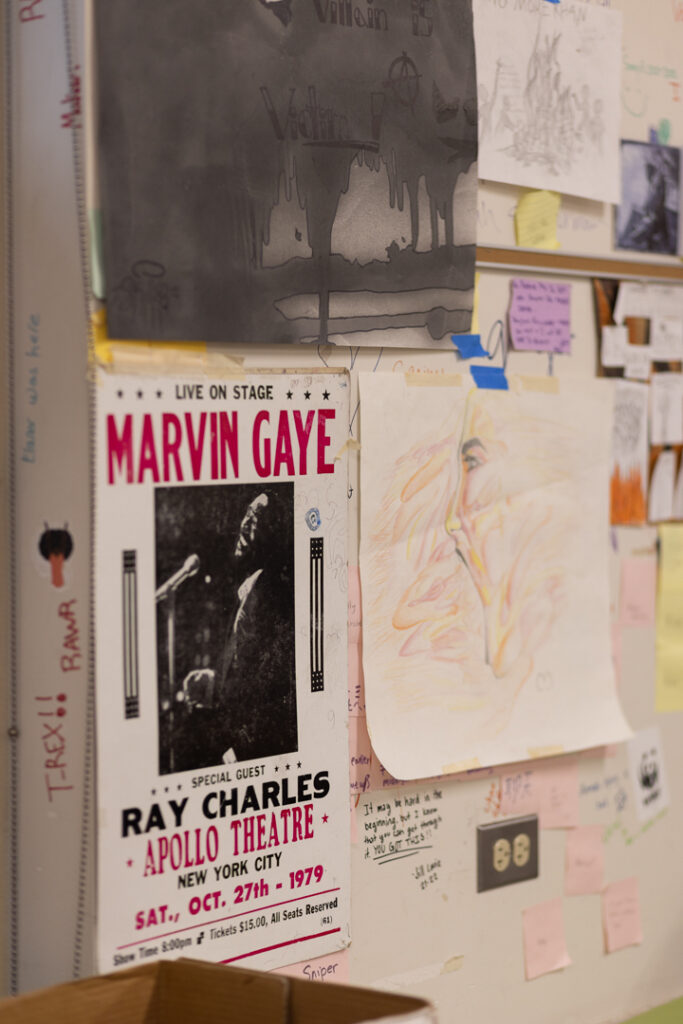

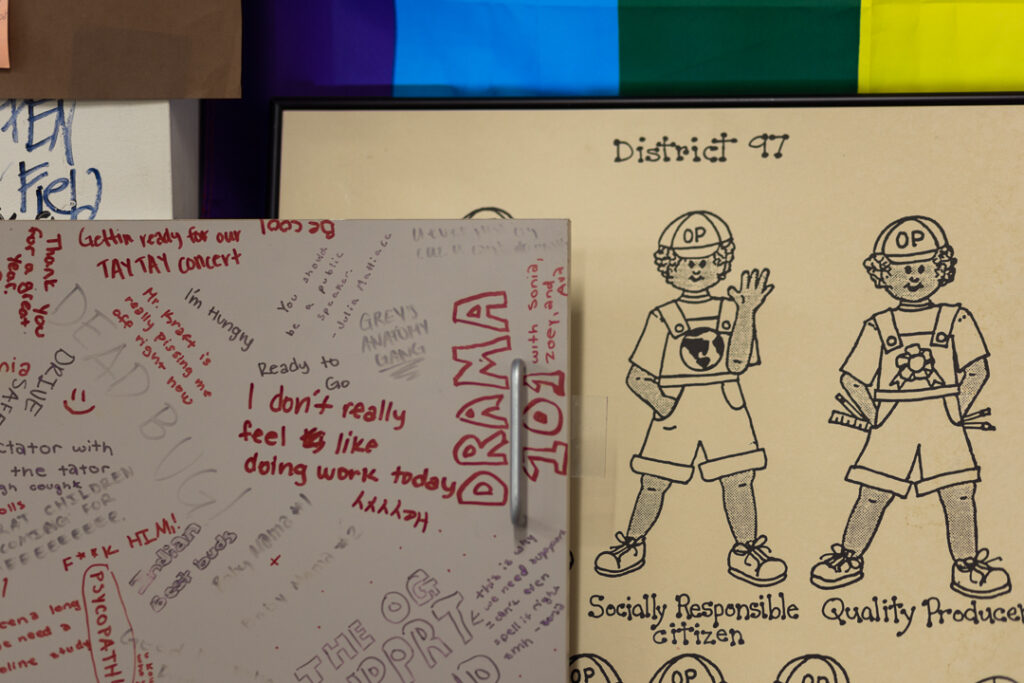

And every single signature that’s on the wall, every signature on the desk, every message, every note, I can tell you the story of every kid who did that.

Every kid who I’ve taught, I can tell you the story.

People won’t come into the room because it’s just so much.

But that’s because every student who’s been in here, I’ve hoped, has left part of their soul behind.

I think we have to strengthen our mentoring. We need to find veteran teachers and connect them to newer teachers. It’s incredibly more difficult to be a newer teacher. When I was a younger teacher, I was given the license to fail. My first principal was amazing and helped me to grow as a teacher. But now I think there’s a greater expectation of specific parameters they want you to meet — and only those parameters. So you have an entire generation of young teachers learning how to be limited.

Mentoring could be a sustainable practice, whereby more seasoned and savvy teachers could help younger teachers see how to fix their compass to a North Star. I think more mentoring is needed, and I just don’t see it happening. And maybe part of that is calculated — the quicker teachers are burned out and turned over, the quicker we can get newer teachers in there, and they’ll cost less. It could be a cost-saving initiative that districts might want to embrace, as opposed to keeping a teacher for a longer period of time. Maybe. But it doesn’t help when students see teachers leave. It doesn’t breed continuity. And it might be fiscally responsible and may even be economically sound, but it’s not educationally pure.

Mentoring could be something that could help younger teachers take risks: help them have a safety net, allow them to be different, and help them to be able to pay the tax that comes with being different. Sometimes you get taxed at a different rate. And it’s important to have a mentor to be able to help you pay off that tax, or at least understand why that tax needs to be paid.

We operate in a world that is all about deadlines, testing, data points, learning targets, and exit tickets. But there are moments of wonder, joy, and awe. There’s something different that you learn every day, and that’s what education should be about. You can’t standardized test it. You can’t optically scan it. You can’t put it on an exit ticket or a Google Form. But man, when you see it…

There are many teachers in our profession who were great students. They nailed school as a kid. School was a fun place for them. They liked it. And so they got into teaching, most likely to replicate that structure of success: ‘I was successful at something, therefore I’m going to do the same thing and you’ll be successful.’

But then there are teachers who got into the business because of precisely the opposite. Their experience at school was horrible, and they don’t want anyone else to go through that. My middle school years were horrendous. I definitely try to airbrush them out of memory. I think one of the reasons I continue in this neighborhood is because I want to help people see that hope is here.

We never grew up with the reality of mental health issues being so real. The issue of teen suicide seemed like nothing more than an afterschool special when I was a teenager. But it’s real, and it’s not going away. And when the history books are written, and people have to ask themselves what side they were on, there should be no ambiguity. There should be no question as to why we chose to be on the side of angels and why we chose to be on the side of helping children. And so I guess one of the reasons why I keep doing this is because somewhere out there, some kid might need something. And if that means that I gotta help, that’s what I’ve gotta do.

We have too many adults who are shirking responsibility. And that’s got to stop. I may not have a kid in my class, but they know they can come to my classroom. If some kid who doesn’t even know me comes to me and says, ‘So-and-so said you’re a good person I can talk to,’ then okay. There’s nothing more important than for a kid to know I’ve got their back. Because sometimes in the lonely world of middle school, that’s all you’ve got.

The ceiling tile project came out of a student’s desire. She was taking my African American Studies class, where we watched the documentary series America to Me. We would watch each episode, break it down, and talk about it. One of the students featured in the documentary talked about how, as a Black girl, she feels left out of so many conversations. And I remember my student shooting up her hand in class when I asked, ‘Was there anything from today’s episode that stuck with you?’ She said, ‘I can relate to that girl’s statement, because I feel left out of conversations today.’

I remember how dignified she was. And I remember, as an eighth grader, how I could never summon the courage to say that and to own it. And I remember telling her privately, ’I don’t ever want you to feel that you are left out of any conversation in my classroom. If you’re not in the conversation, that is not a discourse I want in my classroom.’

Later in the year, I asked if there was anything she wanted to do as a project, and she said, ‘I want to paint a ceiling tile.’ You’ve gotta be on good terms with the custodians for that, but we did find a spare ceiling tile. And it took her about five months. She hit everything in it — from the quote about lifting Black men and women’s voices, to the people in it whose voices were silenced, to the pride flag, to the Black church, to Black Jesus. And I thought, ‘That’s what I need to be doing.’

Then this past trimester, I had another group of students who asked to paint a ceiling tile. They took the notion of Black hair — of Blackness — being silenced and othered, and they put words to it in ways that I couldn’t have imagined. We live in a world that doesn’t necessarily and automatically honor student freedom. But those ceiling tiles demonstrate to me that if you give kids a little bit of space, they can do something to astonish all of us. We can learn from them just as much, if not more, than they learn from us. To me, those ceiling tiles prove it.

Too much of our education is spent looking down at something. We’re not looking up. We never look up. But those ceiling tiles compel me to look up. And they compel kids to look up every day. Every day, I see a kid look up at the ceiling and study some part of it. Some neurological synapses are being created, some pathways are being opened.

That first student came back to visit a couple of weeks ago. She stared at it, and she said, ‘It looks better than I even could have hoped.’

That’s what teaching is. It comes out even better than you could have hoped.

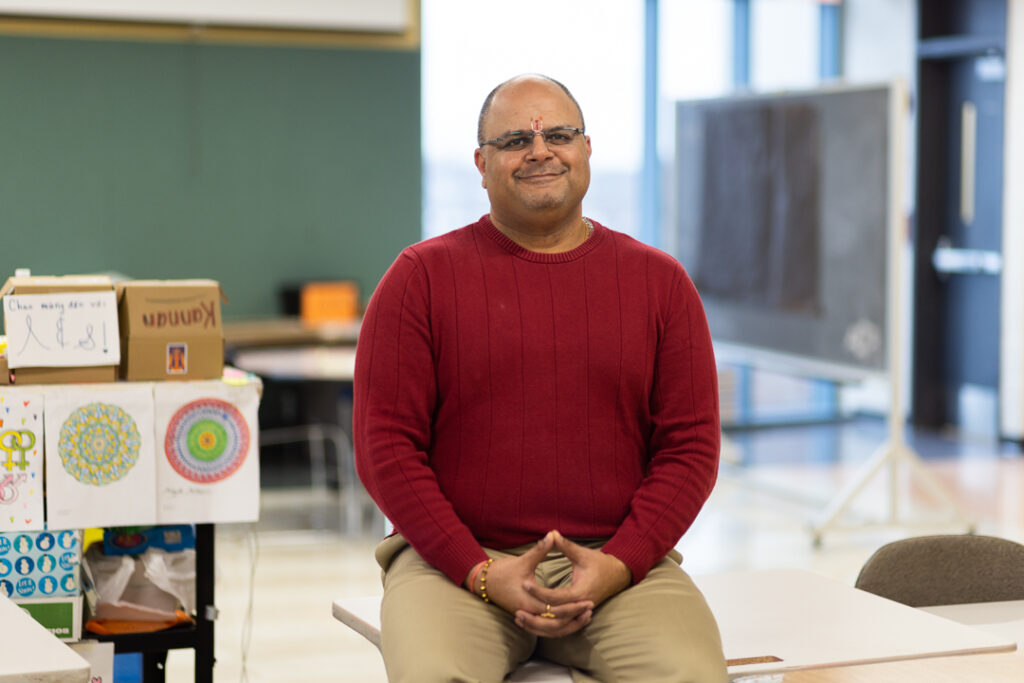

–Ashley Kannan

Teacher at Percy Julian Middle School

Oak Park, Illinois